Ram Manohar Lohia was in the verandah of former chief justice of the Delhi High Court Rajindar Sachar’s house in Chandigarh when he got the news that anti-Hindi protesters in Tamil Nadu were burning periodicals.

“The movement for Hindi is dead,” Lohia told Sachar. This was back in the 1960s when the former judge was the chairperson (Punjab branch) of Lohia’s Samyukta Socialist Party. “When it will be revived I do not know,” said Lohia.

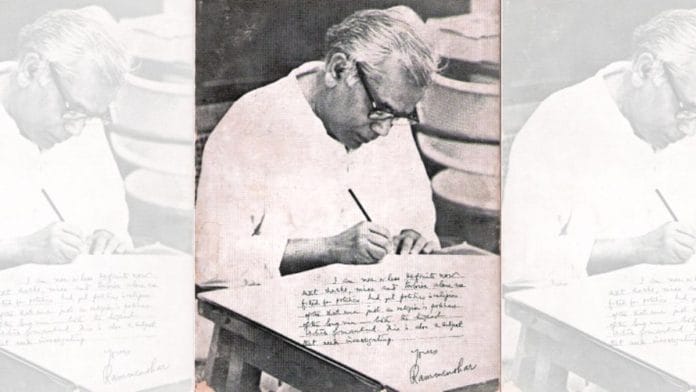

The freedom fighter, socialist, and a fierce critic of the caste system wanted an independent India to rid itself of English. Lohia wanted the colonial language to be removed from educational institutions and public life. He campaigned for the promotion of Hindi across the country.

Did that make him a Hindi chauvinist or bilingual intellectual? Decades after he died in 1967, authors, analysts and scholars have yet to arrive at a consensus. Ramachandra Guha in a 2009 essay, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Bilingual Intellectual’, argues that Lohia advocated not monolingualism but multilingualism.

Lohia always kept channels of communication open with leaders from southern states like EMS Namboodiripad, the former Chief Minister of Kerala.

“Lohia had a substantial argument on the question of language in India. He didn’t want to impose Hindi but he thought that people learn the language of its neighbouring states, so that regional languages would be boosted. He respected all Indian languages,” said Abhishek Ranjan Singh, founder and president of the Delhi-based Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Research Foundation.

Hindi for nation-building

As the leader of his newly formed party, Lohia launched the ‘Angrezī Hatao’ movement in 1957. He wanted Hindi to be the language of the Union government.

“The Centre should correspond with states in Hindi and the states should correspond with the Centre in their regional languages until they learn Hindi,” he wrote. At the same time, he acknowledged the need for district judges and magistrates to conduct proceedings in their regional languages. But Hindi should be the language of the higher courts, he argued.

Lohia presented his formula of language exchange between neighbouring states to Namboodiripad, according to Singh. But nothing fruitful happened. In 1963, Lohia was pelted with eggs in Chennai, Tamil Nadu.

“If his formula had been accepted, then the fight that is happening right now over language would not have happened,” said Singh, citing the ongoing debate over the three-language policy between Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin and Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“Power uses religion and language as weapons and the controversy that has arisen again in Tamil Nadu over language is simply politics,” said Singh. “Lohia was a strong supporter of linguistic unity.”

He’s also become a key figure in the language wars playing out today. Yogendra Yadav, founding president of Swaraj India, called out Home Minister Amit Shah for attributing to Lohia the idea that democracy cannot flourish without Hindi. Lohia had actually referred to ‘lokbhasha’, or people’s language, not Hindi, he wrote for ThePrint.

Sachar said presenting Lohia as a Hindi zealot even against the other Indian languages is an injustice to him.

“No doubt Lohia was against the exclusive small caste of English knowing people being the rulers. He treated all languages of India including Hindi on an equal footing,” wrote Sachar in The Sunday Guardian.

In his centenary year in 2010, authors and scholars debated whether Lohia was a Hindi chauvinist. First, Guha included Lohia in his list of bilingual intellectuals in his essay. But thespian and actor Sudhanva Deshpande compared Lohia’s attitude to language with Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s attitude to religion—calling it cosmopolitan in personal life, parochial in public.

Yogendra Yadav acknowledged that Lohia afforded a special status to Hindi but saw it as a tool for nation-building without being condescending to other Indian languages.

Abhishek Ranjan Singh recalled an incident in 1965, when, on the anniversary of the Quit India Movement in Bihar, Lohia was arrested from the Circuit House in Patna and sent to Hazaribagh. From there, he filed a Habeas Corpus petition in the Supreme Court, which was accepted. Arguing against his arrest in Hindi, Lohia was interrupted by Justice Hidayatullah, who asked him to argue in English.

“Lohia refused to do so. He was proud of his language and the entire case was argued in Hindi,” said Singh, adding that Lohia used to call the compulsion of English as corruption.

Proponent of non-Congressism

Born on 23 March 1910 at Akbarpur in Uttar Pradesh, Lohia was part of India’s freedom movement from Non-Cooperation to 1942 Quit India movement.

However, his role after Independence redefined Indian politics as he broke away from Jawaharlal Nehru’s ideology. Even today, the anti-Congress forces in the Hindi heartland are mostly led by his ideological offsprings: Mulayam Singh Yadav, Nitish Kumar, and Lalu Prasad Yadav. All served in jail during the Emergency as Lohiaite student leaders.

In 1967, under Lohia’s leadership, the Samyukta Socialist Party defeated the Congress in seven states including Uttar Pradesh.

“Lohia was a 21st-century thinker, the last great thinker in the tradition called Modern Indian Political thought,” wrote Yogendra Yadav in 2017 in The Tribune.

But to reduce Lohia to his views on language would be a disservice to one of India’s foremost socialist thinkers. He fought for farmers. He fought against the caste system. He even suggested inter-caste marriages for government servants. He put forward the idea of roti and beti—where women marry outside their caste.

“Ram Manohar Lohia was a very stormy, attractive, much talked about, controversial personality of the fourth, fifth and sixth decade of the Indian political scene,” wrote Indumati Kelkar in her book titled Ram Manohar Lohia.

Lohia also wrote extensively on fundamentalism and liberalism in Hinduism.

“It is commonly accepted that tolerance is a special characteristic of Hinduism. This is not true; though open bloodshed has been largely desisted. The Hindu orthodoxy has always tried to create a semblance of unity by oppressing the non-dominant sects and beliefs, but it has not been successful,” he wrote.

According to Yadav, Lohia has never been forgiven for the three cardinal sins he committed—he attacked Nehru when he was demi-god, questioned upper-caste dominance and agitated for the abolition of the English language.

“This made him persona non grata among the opinion makers of his time, liberals as well as leftists. That is why Lohia is either forgotten or remembered for the wrong reasons,” said Yadav.

But Lohia had faith in his ideas.

“Log meri baat sunenge jaroor, lekin mere marne ke baad. (People will surely listen to me, but after I am dead),” he once said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Ram Manohar Lohia is the intellectual superstar of the Hindi heartland. That in itself tells us how sad and pathetic the situation is in the Hindi belt.

To consider his specious arguments and fallacious ideas as some kind of cornerstone on which to build Indian society speaks volumes about intellectually vacuous the Hindi speaking population of India is.

The political parties inspired by his chicanery and demagoguery are the ones who promoted and championed gundaraj and bahubali culture in the Hindi heartland.