New Delhi: On his visit to Jammu and Kashmir in 1960, Vinoba Bhave received a letter from a dacoit on death row. Tehsildar Singh sought Bhave’s blessings before his hanging and a resolution to the dacoit problem in the Chambal Valley.

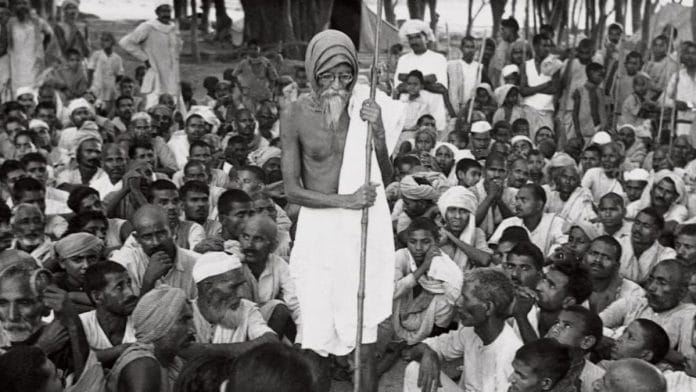

The incident prompted the social reformer’s visit to Madhya Pradesh, where he addressed a gathering, persuading dacoits to give up violence and surrender to the state. Twenty dacoits answered his call, which set a precedent for other surrenders.

Bhave undertook several such initiatives to spread MK Gandhi’s message of non-violence and bring about a social revolution in India, which earned him the first-ever Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1958. The New York Times called him “one of India’s best-known social reformers”, while Time Magazine celebrated his efforts at eliminating untouchability. He was conferred the Bharat Ratna posthumously in 1983.

Despite these laurels, his support for the Emergency garnered him significant criticism in his later years.

The Bhoodan movement

Born on 11 September 1895 in Maharashtra’s Gagode village (Gagode Budruk), Vinayak Narahari Bhave was renamed ‘Acharya Vinoba’ by Gandhi. The pair first met in June 1916 in the Kocharab Ashram in Ahmedabad, following a correspondence through letters.

“When I met Bapu, I felt a unique mixture of peace of Himalaya and the revolution of Bengal present in him. From that moment, my life became dedicated to the cause of peaceful revolution,” Bhave said about the meeting.

However, it was Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Marathi weekly, Kesari, that first inspired the Gandhian leader to dedicate his life to public service.

“When I was nine I developed a passion for Kesari… I studied articles in it on every conceivable topic and it laid the foundation of practically all my learning,” reads Bhave’s quote in Donald Mackenzie Brown’s The Nationalist Movement: Indian Political Thought from Ranade to Bhave.

Like Tilak, Bhave too was fluent in Marathi, English, Hindi, and Gujarati. A Sanskrit scholar, he had mastered about 18 languages. The two also shared an intimate knowledge of Hindu classics and a love for mathematics.

His understanding of the scriptures allowed Bhave to bring his teachings of democratic socialism to the general public through Hindu philosophy. He did this while narrating the Pochampalli episode—which gave rise to the Bhoodan movement—in the book, From Bhoodan to Gramdan.

Some landless lower-caste families in Pochampalli, Tamil Nadu, demanded 80 acres of land, so Bhave implored the village’s wealthy landowners to donate some of their own. A man named Ramachandra Reddy donated a hundred acres, solving the problem with the first bhoodan (land donation). This inspired Bhave to turn the practice into a larger movement, but in his writing, the incident became a divine sign—the “world power” beckoning him to fulfil a mission.

While his message was always steeped in Hindu thought, Bhave also complemented it with teachings from other religions.

When writing about the social structure he hoped to create through the Bhoodan movement, he called it a ‘samya-yogi social structure’, a term taken from the Bhagwad Gita that described the humanistic principle of empathy. He explained the term using a story from the Ramayana and a chapter on roza (ritual fasting) in the Holy Quran.

This esemplastic spiritual outlook was central to Bhave’s work. Another instance of this is Om Sat Sat, a Marathi prayer he wrote using iconography from several religions.

Also read: Pakistan’s Jaun Elia was more than a tragic poet. He was an atheist, Marxist & philosopher

A ‘sarkari sant’

Celebrated throughout India as the ‘Walking Saint’ due to the thousands of kilometres he traversed during the Bhoodan movement, Bhave was also a close associate of Jayprakash Narayan, the second pillar of Gandhian thought in post-Gandhi India.

In a humorous incident, author Narayan Desai once said at the Vinoba ashram in Gujarat, “Our movement, the Sarvodaya movement, has two leaders – one of them is the saint and the other, the politician. And Jayaprakash is the saint.”

Bhave found this highly amusing and heartily expressed his agreement, repeating the utterance in several public meetings. But the innocent incident reveals the spirituality/politics split in the Sarvodaya movement that eventually caused its downfall.

As Narayan started the Total Revolution agitation and was subsequently jailed, Bhave’s inaction sparked anger among his associates. His similar apathy toward the Samyukta Maharashtra Movement had previously led to Marathi writer Pralhad Keshav Atre calling him “Vanaroba” or “monkey” in an essay, perhaps drawing upon Bhave’s own comparison of himself to monkeys in Rama’s army.

In 1975, however, Bhave went a step further and called the Emergency an anushaasan parva (age of discipline). Since he was considered MK Gandhi’s spiritual successor, Bhave’s words were publicised by the Indira Gandhi government as a certificate of legitimacy.

As a result, Bhave, who had remained distant from electoral politics and governance all his life in favour of social justice movements, ended up being labelled a ‘sarkari sant’ (government’s saint).

Having lived as a saint, Bhave also chose a saint’s death. He refused food and medicine, accepting samadhi maran in the Jain tradition. He died on 15 November 1982.

Bhave’s critics have questioned the success of his Bhoodan and Gramdan movements. However, they fail to appreciate the gargantuan effort of the frail, ageing man who walked the length and breadth of the country to distribute 15 lakh acres of land from the rich to the poor.

“What I want is a complete redistribution of land and property, as also of power,” Bhave wrote in From Bhoodan to Gramdan.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)