What is so great about Satyajit Ray?’ This is the one question that most Bengalis are usually asked.

Some may have heard about him in passing, some may have seen his films, but most have come to know of him because Bengalis drop three names casually in conversations: Satyajit Ray, Rabindranath Tagore and Amartya Sen.

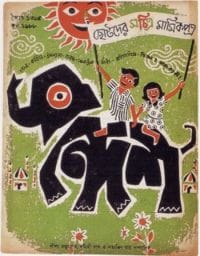

Ray was a polymath — just like his prolific father Sukumar Ray. The Rays of Kolkata dabbled in art and literature and perfected the art of storytelling. From children’s magazines to detective series — they did it all.

Born on 2 May 1921 in an affluent family in then Calcutta, Ray was barely three years old when his father passed away. In a few years, he had to vacate the Ray mansion with his mother, who did needlework to support the family. It was around this time that he met Bijoya, his first cousin, who he would marry later.

Ray was an average student in school, and it was in his college days (he studied in Presidency College) that he fell in love with cinema. His first job was at an advertising agency because of his natural flair for art and typography.

Film

Ray’s first film, Pather Panchali, came to him merely by chance and then went on to become his legacy.

Pather Panchali (Song of the Road) was based on Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s 1929 novel of the same name. Ray came across the novel when someone told him it would make for a good film.

Released in 1955, the film took over two years to complete and Ray also struggled with funding until then chief minister Bidhan Chandra Roy stepped in and the government offered to produce it. Ray writes in his memoir, My Years With Apu, the film had no script and was entirely shot based on his detailed storyboard drawings.

Inspired by Italian neo-realism and the New Wave that championed human lives and social realism in filmmaking, Pather Panchali tells the story of a poor priest Harihar, his wife Sarbajaya, their two children, Apu and Durga, and Harihar’s elderly cousin Indir Thakrun.

Struggling with poverty, it is the family’s little moments that make the film spectacular. One of the scenes is known popularly as the ‘train scene’. Little Apu and Durga run through fields of ‘kash’ flowers to see a train chugging in the distance — there is no song and dance or action sequences, but the mellow lyricism of the scene and wide shot have made it iconic.

The film was first released in the Museum of Modern Art, New York and thereafter in India to a tepid response.

“The Indian film, ‘Pather Panchali’ (Song of the Road), which opened at the Fifth Avenue Cinema yesterday, is one of those rare exotic items, remote in idiom from the usual Hollywood film, that should offer some subtle compensations to anyone who has the patience to sit through its almost two hours,” wrote The New York Times.

It garnered critical acclaim across the world and then the audience started showing up in India. A special screening was held for then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru who was moved by the film and made sure it was India’s entry to the Cannes Film Festival. There was, however, some criticism too. Actress and then parliamentarian Nargis Dutt criticised Ray for depicting extreme poverty in the film.

After Pather Panchali, Ray gave up his career in advertising and became a full-time filmmaker. He would go on to make several notable films like: Devi (1960), Charulata (1964), Aranyer Din Ratri (1970) and Shatranj ke Khilari (1977) — the last being his only Hindi film.

Former prime minister Indira Gandhi had asked Ray to make a film on social welfare based on Nehru. He refused and said, “No, because I’m not interested.”

Also read: Devi to Kashmir ki Kali to Censor Board: Sharmila Tagore is not just Taimur’s grandmom

Women in Ray’s films

Ray’s depiction of women always stood out. In an era where women were mostly props and catalysts, Ray gave them authority and voice. In Charulata, based on Tagore’s novel, we see the lonely wife of a newspaper editor in pre-Independence India being creatively and romantically attracted to another man. The film is a masterpiece in storytelling — Ray’s narrative is subtle, the camera meanders, but beneath lies an intense plot of thrill, danger and longing.

In an interview with Cineaste magazine, Ray called Charulata his most satisfying film. “Well, the one film that I would make the same way, if I had to do it again, is Charulata,” he said.

Although most of Ray’s films were set in Bengal, their language was universal — it spoke to common humanity. This is perhaps the reason why Ray is so popular in the international film circuit.

Ray directed 36 films in his lifetime, including short films and documentaries.

An all-rounder

Ray was an auteur in the true sense — he was the director, editor, he would decide the music, set up the scene and props, design the publicity posters, write the script and cast the actors. Up till 1981, he would make one feature film every year — either based on novels or writing them himself. He is often called the Godfather of Indian cinema.

Literature

Apart from films, Ray, like his forefathers, wrote and published, but only a few Indians know of Ray’s literary genius.

Of his short stories, the Feluda series stands out and have been made into films. Feluda is a detective who lives in Kolkata and is accompanied in his adventures by a young boy called Topshe. Ray himself made some film adaptions of the stories.

Another popular character created by him is Professor Shonku, a scientist whose diary is a world of mystery and inventions. Ray would illustrate the cover of these books as well.

But, the most under-appreciated of all is Ray’s short horror stories — scaring both children and adults alike to date. From shape-shifters to haunted houses, Ray’s horror was never about the gore or the horrific, but about the tense build-ups, the jumpstarts and the terrific.

But, the most under-appreciated of all is Ray’s short horror stories — scaring both children and adults alike to date. From shape-shifters to haunted houses, Ray’s horror was never about the gore or the horrific, but about the tense build-ups, the jumpstarts and the terrific.

He continued his grandfather’s magazine for children — Sandesh. Filled with rhymes, puzzles and stories, the publication of the more than 100-year-old magazine was stopped twice. But, it was restarted partly due to nostalgia and partly due to sudden inflows of funds.

Death

When Ray got the Academy Honorary Award in 1992, he was in hospital suffering from heart and lung ailments. Audrey Hepburn was presenting the award and Ray thanked the Academy from a hospital bed in Kolkata. Twenty four days later he passed away on 23 April.

Interestingly, then prime minister Narasimha Rao had come to visit Ray in the hospital with his daughters. Rao wanted a photograph.

“Mr Ray, three generations of ours are here to wish you and we are all ardent fans of yours, a photo with you will go a long way with us,” he said.

Ray refused in his baritone voice.

“Mr Prime Minister, all these days of my confinement in the hospital, many press cameramen wanted to take my photograph but I turned down their requests. If I accede to your request, what will they think? That I have bowed to the PM as he is in authority. It will also give a wrong signal and appear discriminatory,” he said. The matter was dropped.

“In the evening when his body was taken to the crematorium, the streets were thickly lined with people standing in silent vigil. Many held up placards which referred to him as ‘The King’. The whole city was sunk in an inexpressible sadness: everybody knew that an era had ended, and with it, Kolkata’s claim to primacy in the arts,” author Amitav Ghosh wrote on Ray’s death.

Also read: Cats that wink & science of comets: Sukumar Ray’s fantastic world of literature and creatures

How come author missed Ray’s excellent work Our Film Their first published some timein 1978 by Orient BlackSwan (then Orient Longman) and still in print. The book was also published in French, if I am not wrong in German as well and some Indian language as well.