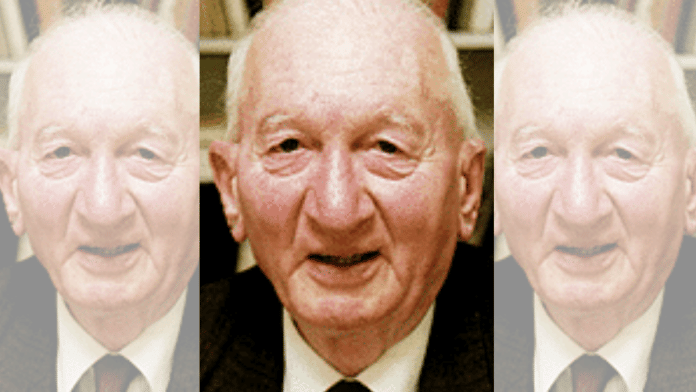

Pakistani archaeologist Ahmad Hasan Dani was a challenger. He revelled in breaking stereotypes and popular narratives of history across the subcontinent. In India, he challenged the notion that Alexander came through the Khyber Pass, instead arguing that it was the Nawa Pass. He also questioned the descent of South Indians from the Indus valley, claiming that he had found “no trace of the Indus Civilisation in the whole of South India.” In Pakistan, he said that the greatest influence “was neither the Hindu south nor the Arab west but central Asia, in its Buddhist, Persian and later Sufi traditions.”

“Time and place do not make a man a witness by right of birth. Witnesses are those who actively mark their eras, or else those through whom an era manifests itself. Dani, according to him, was placed in the first category,” wrote Italian archaeologist Luca M. Olivieri in his biography AHMED HASSAN DANI: (1920-2009).

Born in a village in Chattisgarh in 1920 and raised in Varanasi, Dani lived in East Pakistan (now, Bangaladesh). He was often referred to as the “founding father of archaeology in Pakistan”, since few scholars understood the subcontinent as he did.

His scholarship stretched from the Indus Valley civilisation to Buddhist Gandhara, from Central Asian trade routes to Neolithic rock carvings in the Karakoram. Yet, what distinguished him was not only the breadth of his work, but the clarity of his convictions: that Pakistan’s identity was plural, ancient, and inseparable from the civilisations that preceded Islam.

Early in his archaeological career, Dani challenged the long-accepted belief that Alexander the Great entered India through the famed Khyber Pass. In his book Romance of the Khyber Pass (1997), he noted that Alexander never saw the Khyber Pass at all, instead crossed into the subcontinent via the Nawa Pass — an idea that has since gained some acceptance among historians.

Dani, however, was not just Pakistan’s most influential archaeologist; he was also its most insistent storyteller, determined to remind the nation through history that its past did not begin where political convenience suggested it should, but instead in the actual history of its people and lineage which was syncretic in nature.

He also supervised the exploration of a shrine at Murree, a city in the northernmost region of the Punjab province of Pakistan, which some believed housed the remains of Mary, Jesus Christ’s mother. At Rehman Dherim, a pre-Harappan archaeological site and Baluchistan, he helped unearth traces of proto-urban civilisations that may predate Mesopotamia by a millennium.

Alos Read: Allama Iqbal is the poet everyone quotes and no one understands. He’s beyond ownership

Reconstructing history

The dedication in his 1961 work, Muslim Architecture in Bengal, said, “To my ancestors who left Kashmir about 1850 and settled among the Gonds in Chhattisgadh to spread culture and are now lying buried in Basna – the village of my childhood.”

Born on 20 June 1920, Dani was the first in his household to attend university. That journey took him to Banaras Hindu University, where he studied Sanskrit, which was considered by many an audacious choice for a Muslim student in the 1940s. Dani later recalled that because he was Muslim, he was sometimes forced to sit outside classrooms to hear lectures.

In 1944, he graduated with distinction and received the JK Gold Medal, becoming BHU’s first Muslim graduate.

A year later, Dani found himself at one of the most important archaeological sites of the 20th century. In 1945, he joined Sir Mortimer Wheeler at Mohenjo-daro, where he founded the Taxila University, the vast 4,500-year-old Indus Valley city in Sindh. What Dani uncovered there would shape the rest of his intellectual life.

He argued that Mohenjo-daro was “the first planned city in the world,” complete with sophisticated drainage, urban zoning, and evidence of long-distance trade with Arabia and Mesopotamia. The Indus civilisation, he insisted, belonged alongside Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China as one of humanity’s foundational cultures.

After the Partition in 1947, Dani moved east to what was then East Pakistan.

Dani migrated to East Pakistan, now Bangladesh and from 1947 to 1949, he worked as assistant superintendent of the Department of Archaeology. At this time, he rectified the Varendra Museum at Rajshahi.

For twelve years, (between 1950 and 1962), Dani remained associate professor of history at University of Dhaka, while at the same time working as curator at Dhaka museum. This was the time when he carried out archaeological research on the Muslim history of Bengal, which is held in high regard even today.

In between administrative duties, he completed a PhD at London University on the prehistory of eastern India and undertook research at the School of Oriental and African Studies. His definitive studies of Bengali Muslim architecture remain standard references for researchers and academics.

Dani moved to the University of Peshawar in 1962, where he created the first-ever Department of Archaeology for Pakistan and remained a professor until 1971.

He later established the Faculty of Social Sciences at Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad and the Islamabad Museum in 1993.

“Professor Ahmad Hassan Dani shaped and reconstructed the history of modern-day Pakistan,” Dr Abdul Samad, who is the Director General of the Directorate General of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan, told ThePrint.

“He inspired scholars like myself who now continue to build upon his legacy,” he added.

Also Read: From Ayub Khan to Zia-ul-Haq—Pakistani poet Habib Jalib wasn’t silenced by dictators

From Taxila to Dhaka & Peshawar

To understand ancient manuscripts, Dani fluently spoke Bengali, French, Hindi, Kashmiri, Marathi, Pashto, Persian, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Seraiki, Sindhi, Tamil, Turkish and Urdu. He was also among the first in the world to be able to read several ancient scripts that one sees on rocks and monuments.

Dani authored more than 30 books. His awards included Pakistan’s highest civilian honours and France’s Légion d’honneur in 1998.

At Taxila, the ancient city where Greek settlers left behind Buddhist art and Aegean aesthetics, Dani traced the afterlives of Alexander’s troops. In 1997, he became the founding director of the Taxila Institute of Asian Civilisations.

In a 1998 interview with Harappa.com, he rejected the consensus that modern Dravidian-speaking populations in South India were descendants of Indus Valley refugees fleeing Aryan invasions. “If they migrated,” he argued, “they would have carried something of that civilisation with them, except just the language. But not a single trace has been found.” A 2025 research counters through DNA research that they are Dravidians.

Dani believed Pakistan’s historical orientation lay not primarily toward the Hindu south or the Arab west, but toward Central Asia through Buddhism, Persian culture, and later Sufism.

What appeared to outsiders as a forbidding western frontier, he argued, was in fact “a network of hill plateaus where people have always moved freely.” This conviction drove his work with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), where he led Silk Road expeditions through China in 1990 and the Soviet Union in 1991, reviving scholarly attention to routes closed since 1920.

“As chair of the Pakistan-Central Asia Friendship Association, he wanted to revive ‘a genuine relationship — cultural, historical, commercial as well as religious’, and advocated reopening routes to the north that Soviet rule had shut down in 1920”, said an obituary by The Guardian on Dani.

He passed away on 26 January 2009 in Islamabad due to age-related reasons.

“Dani popularised history by disseminating scientific knowledge in people’s own languages, in ways they could relate to,” Rafiullah Khan, a professor at the Taxila Institute, said in a memorial lecture in 2013.

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)