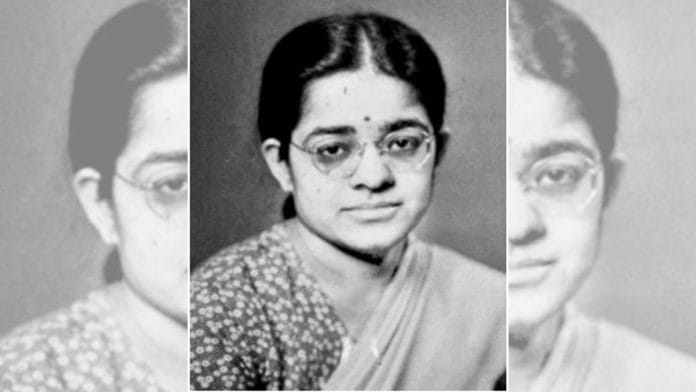

After pioneering microwave engineering in India, Rajeswari Chatterjee, the first woman engineer at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, took on her most daunting task. At the age of 85, she began compiling the archival collection and an alumni book to commemorate IISc’s century-long journey. This was nearly three decades after she retired from the institution as the Chair of Electrical Communication Engineering in 1981.

“She volunteered to help in the early days of the IISc Archives, beginning in 2007 until she passed away [on 3 September 2010]. She helped get us contacts of her colleagues, students, and contemporaries. She gifted several personal photographs and some of her collected material to the IISc Archives,” said Sharath Ahuja, former senior technical officer, at the Archives and Publications Cell, IISc.

Born on 24 January 1922—long before computers or the internet—she defied her era’s limitations by eagerly embracing and integrating new technologies into her life.

“Fiercely independent, she was a bundle of energy—nothing could stop her from doing what she set her mind to,” Ahuja told ThePrint. These traits became deeply ingrained in her personality and remained with her throughout her life.

Her excitement for technology dates back to her PhD years.

“When I visited MIT that year 1949 during a holiday, I saw one of the first computers which was housed in several large rooms! Can you imagine that the modern-day laptops which can be held on your palm can do much more work than those huge computers of the early days?” she wrote in the IISc alumni book published in 2009.

Never called quits

Rajeswari Chatterjee’s dream of earning a PhD abroad was thwarted by the ongoing World War 2, but she refused to give up her aspirations to the crossfire of history.

Undeterred by the circumstances, she sought alternatives to continue her research until the war ended.

“I met Sir C.V. Raman and requested him to take me as a research student. After he found out that my degrees were in mathematics, he told me that he wanted only candidates who had an M.Sc. in Physics with a high first class,” she wrote in the IISc alumni book.

This setback did not deter Chatterjee. Determined to enhance her qualifications for future studies abroad, she navigated an era when societal norms rarely allowed women to pursue education, let alone a career. Unable to relocate to Kolkata, the hub of mathematics, due to family constraints, she set her sights on IISc’s Department of Electrical Technology for a three-year certificate course at IISc’s Department of Electrical Technology.

But her interview presented another hurdle: Professor SP Chakravarthy, the department head, acknowledged her qualifications but advised against enrolling. He listed the challenges she would face as the only woman student, especially during practical training in Kolkata and Jamshedpur.

So instead of pursuing the certificate course, Chatterjee took his advice and joined his lab as a research student. There, she delved into electronics and published papers to strengthen her chances for a post-war scholarship.

In July 1944, she began her research, taking courses in Electrical Communication Engineering, vacuum tubes, electro-acoustics, and line communication. Her efforts yielded three publications—two with Professor Chakravarthy and one with SK Chatterjee, a lecturer who joined the department in 1946 and whom she later married.

Her experience at IISc ultimately secured her a scholarship to study at the University of Michigan in the US, setting the stage for her pioneering career.

Also read: Plants to physics, JC Bose showed the world India had its own way of doing science

To the US & back to IISc

After World War 2 ended in 1945, India, eager to build the country’s industry and economy, announced scholarships for Indian scientists and engineers to study at universities in Canada, the UK, or the US.

Chatterjee became the third woman from IISc—after her friends, physicist and meteorologist Anna Mani and chemist Roshan Irani—to secure a scholarship.

“At last, I felt that I will leave India to go to a more advanced country to learn something different, maybe, for better or worse,” she wrote in the alumni book.

In June 1947, she embarked on a month-long journey aboard the SS Marine Adder to San Francisco, followed by a train journey to Michigan. Chatterjee embraced the adventure, thoroughly enjoying her time in the US.

By January 1949, she had completed her master’s in engineering from the University of Michigan and decided to pursue a PhD in electronics.

However, she postponed her plans to enter doctoral studies by five months to fulfil a government-mandated practical training requirement, and she joined the National Bureau of Standards in Washington, DC where she trained in radio frequency measurements. During this time, she won the Barbour Scholarship at the University of Michigan, which convinced the Indian government to green-light her PhD dreams.

Chatterjee was fortunate to have had great mentors. With guidance from her advisor, professor William Gould Dow, she chose a PhD research problem on vacuum tube trigger circuits, the foundation for early computers.

After five and a half years abroad, she returned to India in April 1954, sailing in style on the Queen Mary and SS Batory—courtesy of the Indian government.

Back at IISc nearly a decade later, she came full circle. This time as the first woman engineer in the Department of Electrical Communication Engineering (ECE).

Also read: Lipid disorders to sweetener—Chemist Sukh Dev blended ancient wisdom and modern science

IISc’s PA-CHA & MA-CHA

Rajeswari Chatterjee and her husband SK Chatterjee built the country’s first microwave engineering lab from scratch, using indigenous materials at a time when grants were scarce. They even introduced courses on microwave technology and satellite communication in the 1960s.

Chatterjee’s contributions to microwave research remain relevant even today, particularly in RADAR technology and applications by the Defence Research and Development Organisation.

Beyond their scientific achievements, the Chatterjees were exceptional mentors, known for their unwavering support of their students.

“She and my father were great mentors to their students,” wrote their daughter, professor Indira Chatterjee, in an email. “We always had students over at our house, many of whom came to discuss issues they were facing—both professional and personal.”

Their deep care and support earned them a special place in the hearts of their students, who affectionately dubbed them “PA-CHA” and “MA-CHA”—short for Papa Chatterjee and Mama Chatterjee, Sharath Ahuja told ThePrint.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)