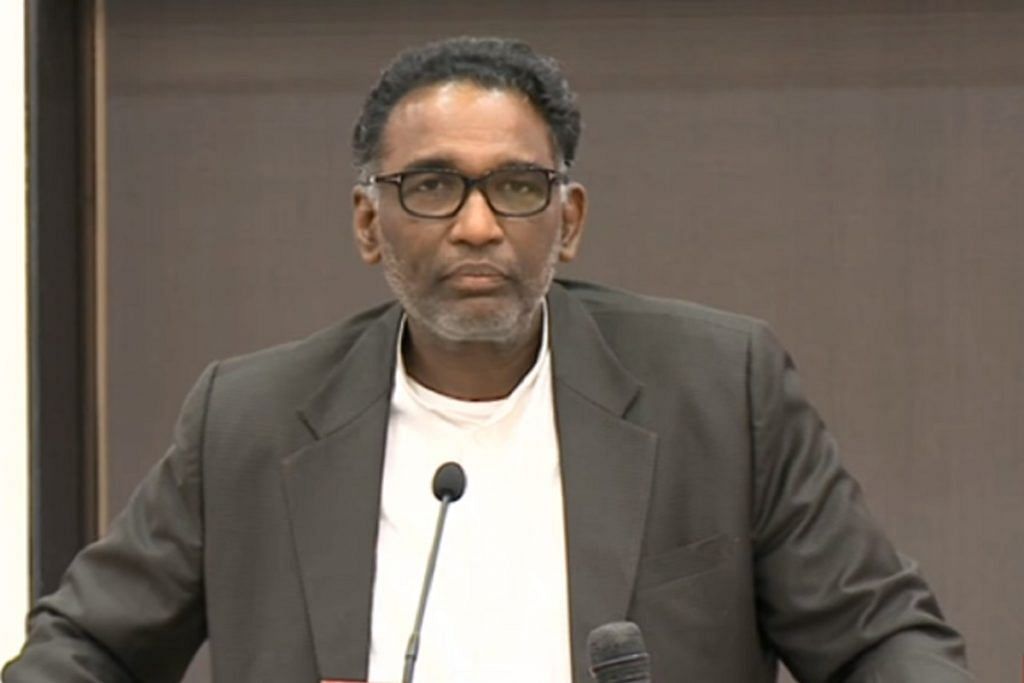

From holding the press conference to ‘judges bribery’ case, Justice Chelameswar, who retires today, has been the flag-bearer of dissent in the higher judiciary.

New Delhi: “Seven years is a good tenure to make a mark personally and contribute to the march of law,” Justice Jasti Chelameswar had said at the Krishna Iyer memorial lecture in 2015.

Months before he retires, the second most senior judge in India’s Supreme Court cannot be faulted if he looks back at his last six and a half years in the apex court and heaves a sigh of satisfaction.

He has certainly made a mark personally, and could also believe that he has contributed to the march of law, considering he is being seen as perhaps the most consequential judge in India’s top court in recent times. The reasons are several.

His critique of the collegium system, through which he was appointed, has shaped the discourse on judicial accountability.

Chelameswar expressed dissent in the ruling on the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). He perhaps saw the fragility of the process more than other judges who struck it down, probably because the same collegium system denied him a chance to be Chief Justice of India.

In 2016, a year after his famous dissent, Chelameswar became part of the same opaque cabal, but when invited to the meetings, he promptly refused to participate in deliberations. Instead, he chose to offer his opinions in writing when files were sent to his office. When he became the number two in that clique, a decision was taken to make all collegium recommendations public.

While that was the judge’s most famous instance of judicial dissent, it was not the only one. In fact, Chelameswar has become so known for his dissenting views – or should it be the march of law? – that the legal fraternity suspects it has something to do with the questionable delay in elevating him to the Supreme Court.

Chelameswar became Chief Justice of the Gauhati High Court in May 2007, but was not elevated to the SC until October 2011, robbing him of the chance to become Chief Justice of India as it placed him behind CJI Dipak Misra in seniority in the top court.

The march of the dissenter

Chelameswar’s other dissents are as political as the NJAC ruling. In 2012, he wrote a contrarian opinion on P.A. Sangma’s petition challenging Pranab Mukherjee’s election as President, on the grounds that he had held an office of profit on the day he filed his nomination. He said it must be given a hearing in open court.

In 2014, he wrote a dissent note against the majority view on holding open court hearings to review petitions of death row convicts.

Months later, Chelameswar, along with Justice Rohinton F. Nariman, would script one of India’s landmark rulings on civil liberties and right to freedom of speech in the Shreya Singhal case. But then, contradicting his latest stand on civil liberties, he upheld a Haryana law that made contesting panchayat elections contingent on having a minimum educational qualification and a functional toilet at home, among others.

On Aadhaar, he again took a liberal view on privacy. He headed the bench that referred the question of whether privacy is a fundamental right to a larger constitution bench, since there were ‘conflicting opinions’ of different benches of the apex court – another institutional process Chelameswar has long criticised.

“There are about 150 that go to constitution benches as different benches of the SC express different views on the same issue. This is predominantly due to the practice of the SC sitting in benches,” he said.

His suggestion was to have all judges of the apex court on one bench, at least for cases involving significant legal questions. Given the number of cases before the SC, and the perennial shortage of judges, the suggestion is not practically feasible. But it explains why he constituted a bench of “five senior-most judges of the court” to hear the controversial case seeking probe into allegations that attempts were made to influence an apex court judge.

“Clever lawyers, more often than not, make emotional appeals to the ‘good conscience’ of the judges to decide cases on ad hoc principles,” he said prophetically in a ruling, but is now haunted by similar accusations.

In the judges bribery case, the three-judge bench said that lawyers — Dushyant Dave, Prashant Bhushan and Kamini Jaiswal — “scandalised the court” by suggesting that their petition be heard by a bench of five senior-most judges, as directed by Chelameswar.

The three-judge bench that heard and dismissed the petition finally refused to even acknowledge Chelameswar in its ruling, referring to his bench as “Court No. 2” — the same court in which a portrait of the greatest dissenter, Justice H.R. Khanna hangs.

Literature, the other L word

But there is more to Justice Chelameswar than law and dissent. He first held public office as Additional Advocate General of Andhra Pradesh in 1995. For the self-confessed admirer of former chief minister N.T. Rama Rao, this appointment came just days after the Chandrababu Naidu-led coup succeeded against Rama Rao.

He was born in Pedda Muttevi in Andhra Pradesh’s Krishna district, a village whose current population is less than 3,000. He credits his school in Machilipatnam, a town 25 km from his village, for introducing him to Telugu literature, a passion he continues to nurture.

Being a voracious reader himself, Chelameswar is a rare judge who opens his personal library to his law clerks and young lawyers. He is often seen recommending books to them.

His interest in Telugu literature and his current position has made him a familiar face in Telugu circles abroad, and he is invited by the Telugu Association of North America to speak to audiences in the United States. Last year, Naperville in the state of Illinois declared 14 October as Jasti Chelameswar day, in honour of his landmark judgments.

As a judge, Chelameswar is known to give a patient audience to young lawyers and senior advocates alike. While listening to lawyers, he often slips two fingers on his cheek, resembling an iconic pose of NTR. Chelameswar is also the only apex court judge to use the microphone in court regularly, perhaps as a testament to his criticism of the court’s opaque mechanisms.

Now, as he prepares to hang his robe and walk away from the hallowed precincts of the Supreme Court, Chelameswar can be rest assured that the country has heard him loud and clear.

This article was originally published on 17 November, 2017