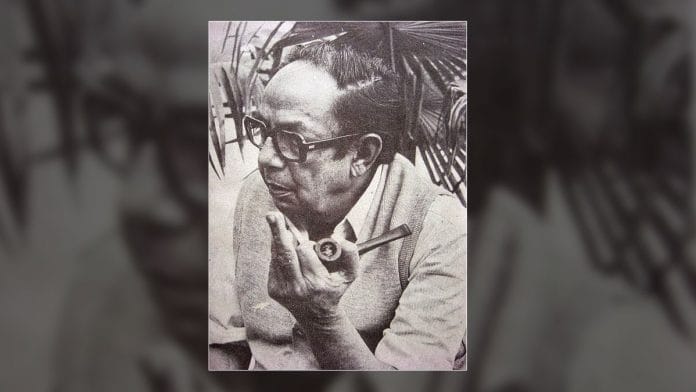

New Delhi: Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya, fondly called Debida, is one of the most renowned philosopher, humanist and scientific thinkers of modern India. He was a staunch lover of reason and a secularist to the core. He often referred to some of his opponents as drumbeaters, who want to return to antiquity, myth and mythology.

Kerala’s first chief minister and Marxist leader E.M.S. Namboodiripad’s remembered Chattopadhyaya’s works as “A sharp weapon against all this revivalism and obscurantism.”

Chattopadhyaya’s secularism and scientific temper are worth remembering at a time when the country’s secular tradition is being challenged by the forces of Hindutva.

On his 26th death anniversary, 8 May, ThePrint recalls Chattopadhyaya’s life and legacy.

Early life

Born on 19 November 1918, Chattopadhyaya belonged to an illustrious family of undivided Bengal. He did his early schooling from Mitra Institution, Bhowanipur, in Kolkata. His father Basanta Kumar Chattopadhyaya was a top-ranking official in the Indian bureaucracy. Both Debiprasad and his brother Kamakshiprasad were gold medalists from the University of Calcutta.

Basanta Kumar was a devout Hindu and a nationalist. He would wash his hands in a bowl of Gangajal after shaking hands with British officers in his office. But, at the same time, he was a humanist and would give shelter to a Muslim fruit-seller’s family in his own home during the horrifying 1946 Hindu-Muslim riots in then Calcutta, according to his granddaughter Aditi.

Chattopadhyaya would often find himself at loggerheads with his father, ideologically, but they had mutual respect for each other too.

Academic achievements

Chattopadhaya had a brilliant academic career. He topped both in BA (philosophy honours) in 1939 and MA (philosophy) in 1942 from Presidency College and Calcutta University, respectively.

It is ironic that he took Indian philosophy as his special paper in MA since throughout his later life he waged a relentless battle against Vedanta and other forms of immaterialist philosophy.

He later joined City College, Calcutta, as a lecturer in philosophy. He went for extensive lecture tours across India and abroad while a visiting professor in the Universities of Calcutta, Andhra, and Poona. He also received a D.Litt. from Calcutta University, a D.Sc. from USSR Academy of Sciences, Moscow, and was elected a member of German Academy of Sciences, Berlin.

He also had a unique apathy towards awards. Both he and his friend and mentor Samar Sen sold their academic gold medals to get their books of poems published as they did not want to ask their parents for money.

During his days at Calcutta University, Chattopadhyaya learned a lot about philosophy from Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Surendranath Dasgupta, who were stalwarts of traditional Indian philosophy. He then went on to pursue the study of the beginnings of scientific thought in ancient India.

Linking science and philosophy

By the end of the 19th century, nationalism witnessed a resurgence in India. Along with it, came the demand to project the past glories of India in science, technology and philosophy. The only source material available then was Vedic literature due to lack of archaeological evidence.

Social reformer Bal Gangadhar Tilak traced the origin of the first phase of Vedic literature to 6,000 BC. Then the sites of the Indus Valley Civilization were excavated in 1921. It was an urban civilization and the use of burnt bricks was first found there in India.

Chattopadhyaya pointed out that there was a casual reference to astronomical phenomena in the Vedanga Jyotisa and Vedic literature, which refer to a period without any Aryan settlement. This pointed to the Indus Valley civilisation.

Unlike many other scientific historians who confined themselves exclusively either to science and scientific ideas or to the development of technology, Chattopadhyaya refused to deal with science without referring to philosophy.

Instead of starting off with the Vedic times, Chattopadhyaya began with the urban civilisation of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, pointing out its salient features, particularly the absence of iron.

He then moved on to study the period of Second Urbanisation by 1977. He busted the popular myth that was prevalent after the Industrial Revolution that a city was the image of society itself.

Chattopadhyaya asserted that newly emerging industrial cities were something to be explored as a problem in itself, something that could not be comprehended by the use of a few labels or categories.

His works

Chattopadhyaya’s book Lokayata:A Study in Ancient Indian Materialism (1959) is considered to be his magnum opus and a cornerstone of Indian Marxist philosophy.

Joseph Needham, globally recognised for his multi-volume Science and Civilisation in China, wrote to Chattopadhyaya: “Your book will have a truly treasured place on my shelves. It is truly extraordinary that we should have approached ancient Chinese and ancient Indian civilizations with such similar results…”

His other prestigious books include Indian Atheism, What is Living and What is Dead in Indian Philosophy, Religion, and Society, among others.

In his works, Chattopadhyaya attempted to discover the material basis of the ancient Indian philosophy. He subsequently went on to publish three volumes on the history of science and technology in ancient India.

Similarly, in his historical work, he sought to locate the material basis of scientific ideas. He did not think it proper to dissociate history and philosophy from technology.

The “how” was as important to him as “what” and “why”. His study of the Śulbasūtras, which is described roughly as Protogeometric, pays as much attention to “brick technology” as to the geometrical theorems that followed from the arrangement of bricks in the Vedic sacrificial altars, mostly referred to as Cit, Citi, Vedi.

Apart from his works on philosophy, Marxism, and history of science, Chattopadhyaya has a number of books for children to his credit. He was a keen advocate of the people’s science movement and edited a collection of essays by eminent Bengali scholars such as Ram Mohan Roy and Satyendra Nath Bose.

Chattopadhyaya later worked as a guest scientist in the National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies, New Delhi. He died on 8 May 1993.

Also read: Sri Aurobindo, a staunch nationalist who turned into a philosopher