In his last speech on 31st December, PM Narendra Modi justified demonetisation in November 2016, by quoting some peculiar lines of poetry.

“Kuch baat hai ki hasti mit’ti nahin hamari (There’s something about us that our existence can’t be erased),” he said.

Post-demonetisation, Modi added, the people of India had lived the true meaning of these words through their resilience.

And it wasn’t the first time an Indian politician had quoted these lines. In 1991, Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh too used them to stress India’s strength and persistence in his iconic budget speech.

More recently in Pakistan, Army Chief Asim Munir used the words in his speech to Overseas Pakistanis to highlight Pakistan’s superiority among Islamic nations.

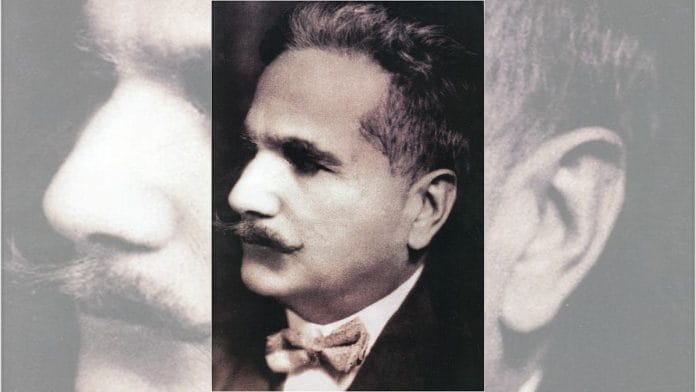

More than six decades after India’s Independence, Modi borrowed these lines from Pakistan’s national poet, Muhammad Iqbal. Taken from Iqbal’s Tarana-e-Hindi (1904), the words have found surprising champions over the years, beyond these occasional tributes. But Iqbal doesn’t sit comfortably in modern Indian political history. The Indian Right often dismisses him as the intellectual architect of Muslim separatism, and the Left disagrees with his ideas of nationalism.

Commonly known by the honourific, Allama, Iqbal is revered on the other side of the border as the ideological father of Pakistan. His image is printed on currency notes, he is praised in state textbooks, and his birthday is a national holiday.

For Pakistani journalist Rana Muhammad Asif, Iqbal is the poet everyone quotes—but no one truly understands.

“Perhaps the reason Iqbal remains so widely quoted is that he still offers something to everyone—nationalists, secularists, Islamists, and revolutionaries alike. But to truly understand him is to confront the uncomfortable: that his vision defies simplification, and his legacy resists ownership,” he told ThePrint.

Nationalism, socialism, Islam & Iqbal

Allama Iqbal’s legacy is often associated with the two-nation theory. Long before the word “Pakistan” found currency, the poet stood at the pulpit of the 1930 Muslim League session in Allahabad (now Prayagraj) and spoke of a dream.

“The formation of a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims,” said the philosopher-poet.

And yet, the same Iqbal who inspired Partition through his political sermons was also a searing critic of religiosity. As Raza Mir notes in his 2022 book, Iqbal: Poet of the East, he was a poet of the proletariat.

While he has been dismissed by progressives and socialists for his nationalist ideas, Iqbal dismantled not only class structures but religious authority in his first Urdu poem in 1928, Mir wrote.

“These temples, churches, mosques—they’re all stomachs, and we are the morsels. May God protect the defenseless poor!” wrote the poet.

Iqbal’s verse wasn’t afraid of confrontation—with god, with the State, or with the self, Mir added. His Lenin – Khuda ke Huzoor Mein portrays the Russian revolutionary demanding justice from god himself.

It’s this revolutionary spirit that led early Leftist thinkers like Sajjad Zaheer to seek Iqbal’s endorsement when founding the Progressive Writers’ Movement.

Yet, the Left wasn’t always kind to him. Sahir Ludhianvi famously responded to Iqbal’s radical call to burn barren fields with a plea for redistributive justice instead of destruction. Even progressive writers like Ali Sardar Jafri and Mulk Raj Anand viewed Iqbal as a contradictory figure, both as a revivalist and a revolutionary, Mir wrote.

“Iqbal once proclaimed that his personality had two facets: he was practical and businesslike externally, but also someone who lived in a dream world and transcended reality internally,” said Jamia professor Anisur Rahman, who wrote The Essential Ghalib (2024).

“Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru once told him [Iqbal] that he was a patriot, whereas Jinnah was a politician, and there were many similarities between them,” Rahman added.

Also read: Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan awed Oxford, charmed Mao. Stalin called him ‘Professor’

Intellectual architect of Partition

Born in 1877 in Sialkot, now Pakistan, Iqbal studied in Lahore, Cambridge, and Heidelberg. He was a philosopher, political thinker, and, most of all, a rebel who refused to be boxed in.

He is best known in India for writing Saare Jahan Se Achha (1904), a hymn to Indian unity. By 1930, however, he was advocating for a consolidated Muslim-majority state in Northwest India. This ideological pivot has led many in the country to brand him the intellectual architect of Partition.

His verse, Tarana-e-Milli, had a pan-Islamic message, and was seen as promoting a unified Muslim identity over national boundaries. This led to Ludhianvi parodying the poem in the film, Phir Subah Hogi (1958).

Just before his death on 21 April 1938, Allama Iqbal entered a public debate with Deobandi scholar Hussain Ahmad Madani over whether Islam and nationalism could coexist. In his 2012 book, The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal, author Iqbal Singh Sevea wrote that the two clasjed through letters, speeches, and poetry. Madani argued that Islam allowed for a political identity based on territory, citing Quranic sources and Islamic history. Iqbal vehemently disagreed, calling nationalism “the greatest enemy of Islam”.

Also read: Morarji Desai scolded Vajpayee for drinking alcohol. He was India’s puritan PM

Misunderstood poet of East

Today, Iqbal is remembered through State-managed myths. In Pakistan, he is the philosopher who dreamed of the nation. In India, he is either a nationalist poet or a scapegoat for Partition.

In 2021, Iqbal’s last surviving daughter, Munira Salahuddin, recalled him as a gentle father who admired the Turkish independence struggle and believed education was the path forward. His descendants run Dabistan-e-Iqbal, a Lahore-based institute dedicated to teaching his philosophy without state interference.

“On the failure of the democratic model in Pakistan, Iqbal’s couplets are misquoted to justify wrong actions,” wrote former Pakistani ambassador Muhammad Tariq.

Pakistani poet Atif Tauqeer views it differently.

“Iqbal’s verses are now used more for political sloganeering than for appreciating their rhythm, nuance, or philosophical depth. His true legacy lies in the imaginative force, linguistic brilliance, and moral boldness of his work,” he said.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)