Even as Afghanistan and Pakistan have negotiated a temporary ceasefire to end fighting at the Torkham Border Post on the Durand Line, history and experience have shown it is unlikely to last long. Drawn by colonial bureaucrat Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, the border has been rejected by generations of Afghans, who claims it cuts through their tribes, clans and communities. Pakistan is determined not to give an inch, but its strategy isn’t working.

New Delhi: The ending, so local people insist, was delivered by an enraged elephant which threw its rider from its back as it passed through an ornamental gateway in Tunk, near the city of Dera Ismail Khan. Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, it is said, was crushed under the elephant’s feet and later buried, or what was left of him, in the graveyard of St. Thomas Church. The violent death seemed fitting, many whispered, for the English diplomat had carved the land of the Pashtun tribes into two, cutting apart villages, severing clan from clan, and laying the foundation for endless bloodshed which continues to this day.

Like all good tales, I wish the story was true, but it isn’t, sadly. Henry Mortimer Durand, in fact, died in the beautiful Somerset village of Polden, very far from the nearest rampaging elephant. The grave in Tunk, which local people talk about, is in fact of his father, Henry Marion Durand, who was Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, and who did, in fact, die of rampaging elephant.

Hi and welcome to this week’s episode of the Print Explorer. Well, we take a deep dive into the tangled weeds of myth-making and misperception that surround some of the complex conflicts playing out around the world and try to get to the roots of the issue. Last week, Afghanistan and Pakistan agreed to a three-week ceasefire at the Torkham border crossing, which has seen heavy exchanges of gunfire between troops of the two countries.

There have been several similar rounds of fighting, in September last year for example, and before that in February 2023, and this has happened even though the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan or the Taliban has taken power in Kabul. Each time, the fighting has been sparked off by the construction of Afghan military positions in what Pakistan claims is its side of the border. This round of fighting again was sparked off by Islamic Emirate troops or the Taliban building a small bunker inside what Pakistan says is its territory.

I am sure you are asking yourself the obvious question, wasn’t the Islamic Emirate installed in Kabul with decades of help from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), precisely so that a friendly regime could secure the border? If so, why are Islamabad and Kabul still shooting at each other? As the saying goes, once is an accident, twice is a mistake, and three times is a bad habit. The Afghan-Pakistan conflict is deeply ingrained and the story at the Torkham border is deeply ingrained. To understand the story playing out at the Torkham border, we have to go back to the son of the man who fell off the elephant.

Also Read: Will Trump finally revive post WWII plan for Europe to create its own military

The border wars

Late in the 19th century, Tsar Alexander II’s forces stormed their way into the Central Asian Emirate of Kokand, one of the Silk route centres for trade in cotton, silk, livestock, kerosene, matches and slaves often seized from Russian territory. Although the Tsar’s generals Mikhail Skobelev and Konstantin von Kaufmann made short work of the Emirate and soon brought the Ferghana Valley into Russian control, they found themselves confronted by ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbek revolts. Those revolts were to lay the foundations for today’s threats from the Islamic State in Central Asia, but that’s a story for another day.

For our story right now, the important part is the panic Russia’s proximity with Herat in eastern Afghanistan caused in Imperial Britain. As I discussed in the last episode of the Print Explorer, which was on British railway lines in Balochistan, Britain had long practiced a policy of what was called masterly inactivity on its empire’s northwest borders. Masterly inactivity basically meant leaving alone the tribes of what is today Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

The Russian advance, though, created fears in London and in New Delhi that the Tsar might soon move down the Khyber Pass to the gates of Delhi, just as so many ancient warlords and conquerors had done. The advocates of the so-called forward policy, wanting British troops up on the border, pushed for action and they got it. Now, this wasn’t a decision lightly made.

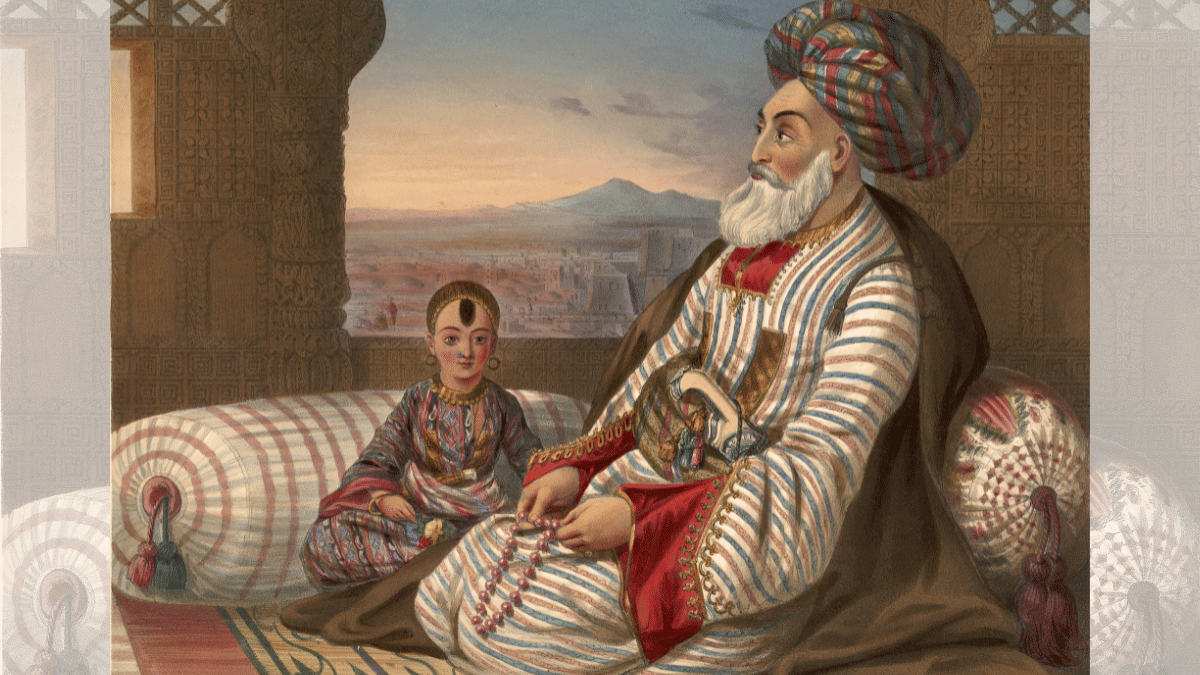

In 1839-1842, the British had occupied large parts of southern Afghanistan and ended up suffering one of the most humiliating defeats in their military history. Then a Russian-backed advance on Herat had been the cause of the British invasion of Afghanistan. Amir Dost Mohammed Khan, the Afghan ruler, who had initially been supportive of the British, was deposed and replaced with Shah Shuja.

To cut a long story short, the British were forced to withdraw from Kabul and massacred on their retreat. Lady Florentia Sale, who was on that ill-fated retreat, later wrote, ‘The sight was dreadful, the smell of the blood sickening; and the corpses lay so thick it was impossible to look away from them, and it took some care to guide my horse so as not to tread upon their bodies.’

Lots of people, their imagination fuelled by pop media, see that battle as evidence that Afghanistan is the graveyard of empires, a kind of unconquerable heart of darkness. Well, no, the British didn’t become a great empire by being broken by one disaster, or for that matter, many.

The so-called Army of Retribution under Major General George Pollock eventually rescued the hostages and levelled parts of Kabul, to make their point. An Indian spy, by the way, had a very big role in that operation and maybe I’ll tell his story in a future episode. Former Emir Dost Mohammed Khan, who had handed himself into British custody in November 1840, was quietly released and made king again.

The British realised, despite their victory, that it cost too much to govern and control Afghanistan. There was no revenue to be raised from the country either, which is why so many warlords invaded the plains regularly. Paying Dost Mohammed to run the country for them was a lot cheaper and just as effective.

Good geopolitics, after all, isn’t about national ego or emotion. The Tsars’ push towards Herat though led the British to reconsider and they went to war again in Afghanistan in 1878, this time passing through the Bolan Pass, Khyber and Khurram to overthrow the pro-Russian Emir Sher Ali. The Afghans won one important battle along the way, the Battle of Maiwand, but were eventually crushed by superior British arms at Kandahar.

The Durand Line

Even though the British had won Afghanistan for the second time, they’d learnt from bitter experience that it cost too much to hold on to. Abdur Rahman Khan, a grandson of Dost Mohammed, who had survived the fatricidal wars which broke out following the death of the old man, crossed back into Afghanistan from Russia in 1880 and laid claim to the throne. Now, Dost Mohammed was insistent he would not accept the presence of a British resident, the kind of political agent who monitored the activities of the courts of other princely states in British India.

But he did accept the Treaty of Gandhamak, which had ceded the Khyber Pass and the districts of Khurram, Pishin and Sibi to the British. For his sacrifices, Dost Mohammed was given a purse of 6 lakh rupees, then about 60,000 pounds, which would be doubled in 1893. The Emir wasn’t a pushover, clearly, but he was under tremendous pressure.

Abdur Rahman had managed to reclaim Kandahar and Herat in 1888, which had earlier been severed from Kabul by the British, who tried to set them up as independent kingdoms. Alongside, he fought and crushed two major ethnic rebellions. Meanwhile, the Russians had taken Panjshir in 1885, bringing them to within a few days’ march from Herat.

So, the Emir had that to think about too. The real problem lay ahead though. Treaty or no treaty, where exactly did the empires claiming Afghanistan actually have their borders with this country? As Foreign Secretary, Durand was deputed to Kabul in 1893 with instructions to achieve two ends, the great Indian diplomat Satyendra Lamba has written.

First, he was to persuade the Afghans to relinquish their claims to the Transoxus river area of Roshan and Shignan, which were also claimed by Russia under an 1872-1873 Anglo-Russian agreement. In return, he would be given the Wakhan Strip that was to separate Kashmir from Chinese territories. The second bit of the deal was more contentious.

This was an agreement to divide the Pashtun belt into respective spheres of influence of British India and Afghanistan. In November 1893, Amir Abdur Rahman Khan and Mortimer Durand thus entered into the agreement, which created the Durand Line. There are seven short articles.

In the many decades since, there have been enough disputes over all of these articles to write a PhD thesis on. For our purposes, though, one of these disputes was critically important. The preamble of the agreement refers to the fixation of the limits of the spheres of influence between Britain and Afghanistan.

Which bits do you run? Article 4, though, talks about demarcating a borderline. So which was it that they agreed to? To just carve up spheres of influence, or to have an actual border? The small-scale map attached to the agreement doesn’t help resolve this dispute. The actual process of physically transferring the frontier line depicted on the map appended to the agreement onto the ground was to prove extremely challenging.

The map was drawn on a scale which makes the line itself four miles thick. To make things worse, it contains several topographical errors. In places, its cartography does not agree with the textual representation of the terrain in Article 3 of the agreement.

Leaving aside the question of legality, though, Amir Abdul Rehman and his vassals, including the Badshah of Kunar in South Afghanistan, continued to demand taxes and declarations of loyalty from regions south of this line, in areas like Chitral, which were now ostensibly under British sovereignty, or this British sphere of influence. The Durand Line, moreover, tore through communities which were united by centuries of history and kinship. It even cut through houses.

It ran right through Kafiristan in the northeast region of Pakistan, which has a very unique ethnic and religious population mix. In the south, it cut through the tribal areas of the Baloch people and also divided the core Pashtun areas without any regard to tribal identity or sub-tribal identity. The establishment of the Durand Line also ensured that Peshawar, traditionally the summer residence of the Afghan Amir, which was conquered by the Sikhs in 1835, was ceded to the British.

But Peshawar had deep historical ties with Kabul, which continue even today. For these reasons, and because of Afghanistan’s growing flirtation with an economically resurgent Germany, the British went to war again in 1919. This time the conflict was short, sharp and decisive.

The peace treaty signed in 1919 forced Afghanistan to consent to seeing the Durand Line as a frontier. Another critical change was to ensure territory controlled by the Mo’man tribe was firmly handed over to the British, with Afghanistan giving the British the Torkham Ridge. That, of course, is exactly where fighting broke out this month.

Also Read: Train hijack by Baloch insurgents in Pakistan holds critical lesson—railways can drive geopolitics

A rocky path

Following the Third Afghan War, the British maintained something resembling peace in their borderlands. Something resembling peace because they regularly bombed and strafed ethnic Pashtun and Baloch rebels into submission. The Afghans were willing to take this kind of brutal treatment from an imperial hegemon, but not the fragile Pakistani state which succeeded it.

Things went downhill within months of the independence of Pakistan. In the summer of 1948, Pakistani troops slaughtered hundreds of unarmed supporters of the great Pashtun leader Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in what has become known as the Babra Massacre. Even worse, Pakistani combat aircraft bombed the anti-colonial rebel Haji Mirza Ali Khan Wazir or the Fakir of Ipi at the village of Mangolghi, killing 23 of his supporters and their kin.

To many Pashtun in Afghanistan, it began to look like the post-imperial age was exactly like the imperial age. And they didn’t like it. Afghan-Pakistan relations were descending into the abyss by 1950.

To push back against Pashtun nationalist sentiment, Pakistan closed the border and blocked trucks from carrying fuel to Kabul. The Afghan government responded by turning to the Soviet Union for help. Then, Pakistan allowed King Amanullah’s pretender brother Amin Jaan to reside in Waziristan just across the border.

Kabul newspapers responded by declaring the Fakir of Ipi the President of Pashtunistan and publishing accounts of state assemblies being created for what they described as Northern and Southern Pashtunistan, i.e. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. In October 1950, a tribal Lashkar or raiding group from Afghanistan even tried to seize the Bogra Pass leading to Quetta. This sparked off full-blown fighting with the Pakistan Army.

The declaration of West Pakistan to be one unit, a single province, just like East Pakistan was a single province, further drove Pashtun and Afghan disaffection. Tribal groups began regularly clashing with Pakistani troops in regions like Zoab. Mobs in Afghanistan attacked Pakistani diplomatic missions, and transit and trade were regularly disrupted.

In July 1973, a military-led coup brought the regime of Mohammad Dawood Khan to power in Kabul. Dawood Khan was a frank nationalist and his relations with Pakistan were poor from the outset. Dawood asserted Afghanistan’s claims to the ethnic Pashtun enclaves of northwestern Pakistan.

In response, the regime of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto backed Islamist groups who were facing the wrath of the new political order in Kabul. The Islamists who would become prominent in the course of the anti-Soviet jihad, people like Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Burhanuddin Rabbani and Ahmad Shah Masood, had taken refuge in Pakistan by 1974. A political movement made up of these Islamists and clerics was soon cobbled together by the Pakistani ISI.

They were used to retaliate against Afghan support for Baloch and Pashtun nationalists. In July 1975, small groups of trained Islamists, armed and funded by Pakistan’s covert services, infiltrated into Afghanistan’s provinces, hoping to stage a coup. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its limited resources, the coup of 1974 degenerated into a rout, with Afghanistan’s intelligence and military services soon kicking the rebels back to Pakistan.

Islam, or ethnic identity?

Following the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the long jihad which followed, Pakistan gambled that its support of Islamists would bring ethnic Pashtun sentiment to a close once and for all. After all, after the invasion, Pakistan and Kabul were united in a war fought in the name of Islam against foreigners who were cast as seeking to crush the faith. Events after the rise of the second Taliban emirate though show ethnic identity isn’t as weak as the ISI might have imagined.

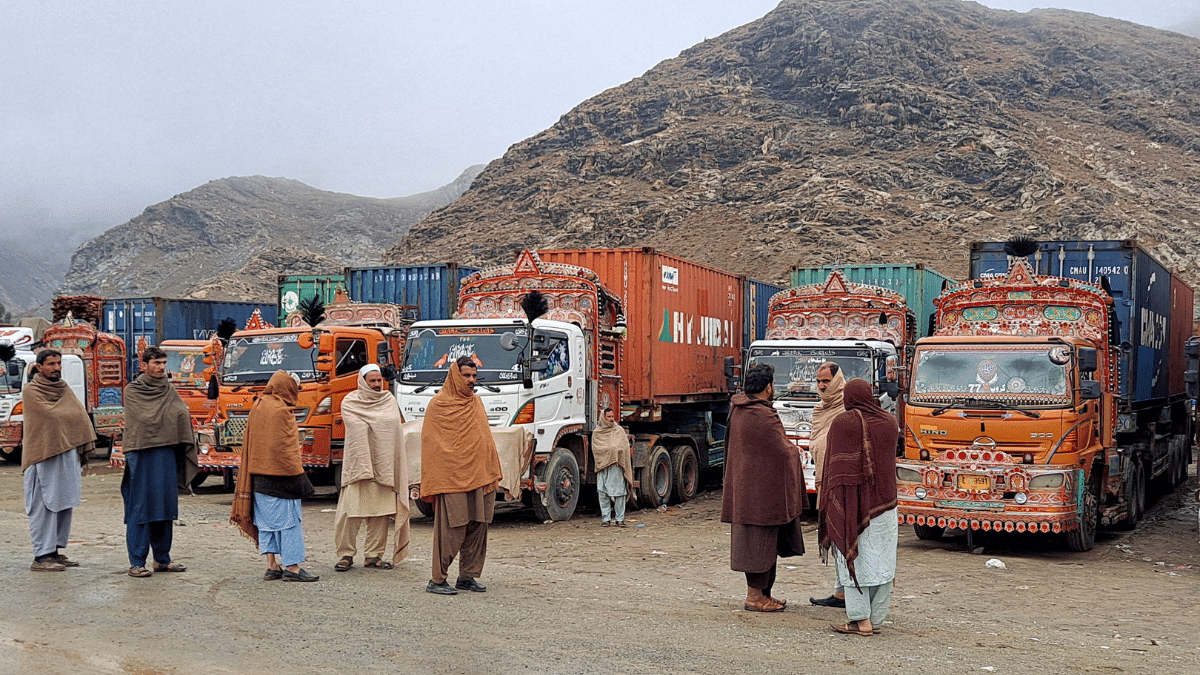

Feelings of Pashtun brotherhood or nationalism haven’t disappeared because of the creation of a political movement in the name of Islam, any more than Bengali nationalism disappeared after the creation of Pakistan. From the very first days of the Islamic emirate fighters occupying Kabul and then arriving at Torkham and Khyber, they made their anger against the Durand Line known. Go through YouTube, you’ll find many videos of Taliban fighters mocking Pakistani troops on the other side of the Durand Line and vowing to attack them.

The Pakistani state has been trying to make with steel what could not be achieved through political means. From 2017, it set about completely fencing the Durand Line. The Torkham crossing point between Nangarhar and Peshawar now requires a visa and pass for Afghans to get into Pakistan and for Pakistanis to go the other way.

Fencing though has caused massive public resentment in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Afghan republic used to condemn the fence with the strongest of statements. President Ashraf Ghani at a public gathering in Paktia said, ‘Those people who want to divide us with barbed wire should think again. Aeroplanes and bombs didn’t separate us. The fence only needs a few cuts’. He added that the fence is incapable of, ‘erasing history, love and brotherhood are inseparable’.

Even now with the Taliban in power, the fence isn’t doing much in practice. From jihadists to smugglers and just ordinary citizens, coming and going across the Durand Line seems to be almost as easy as ever. In Chaman city of Pakistan’s Balochistan province, interviewers told one group of scholars that it’s impossible to distinguish between the residents of Chaman and the Pashtuns of neighbouring Shpin Boldak, Kandahar and the wider southern region of Afghanistan.

Inhabitants of the border cities predominantly hail from the same Achak Zai tribe. Many are related by marriage. Large numbers of Chaman residents have land, homes and family members living in Shpin Boldak and Kandahar.

The Islamic Emirate’s officials, to the dismay of Islamabad, have been speaking the same language Ashraf Ghani did. Islamic Emirate Director of Finance and Administration at the Ministry of Martyrs, Kalimullah Afghan, speaking to a gathering on 24 November 2023, told Pakistanis, ‘Afghan refugees didn’t live on your soil. They lived in autonomous and occupied Pashtunistan. They lived either in Balochistan or Peshawar, which is occupied Pashtunistan, the land of Greater Afghanistan.’

He wasn’t the only one talking like this. Calling the Durand Line an imaginary line, Acting Minister of Borders and Tribal Affairs, Noorullah Noori also said, ‘we neither have an official border with Pakistan nor do we have a zero point with Pakistan.’

And Acting Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Abbas Tanukzai also said, ‘we have never recognized the Durand Line and we will never recognize it. Today, half of Afghanistan is separated and is on the other side of the Durand Line. But Durand is the line which was drawn by the English through the heart of Afghans.’

The heart of Afghans. Remember exactly what Ashraf Ghani called that border. The clashes on the Torkham border on the surface are efforts by the Islamic Emirate and Pakistan to jockey for influence.

Pakistan wants to show Kabul it can choke livelihoods and the Afghan economy, if terrorism continues across the border. The Islamic Emirate, for its part, wants to show it can escalate conflict in the Afghan-Pakistan borderlands and inflict real pain on Islamabad. Yet, whatever deal the two sides arrive at is pretty much certain not to stick.

True peace between Pakistan and Afghanistan needs acknowledgement that the borders drawn by colonialism might not always be the best way to organize the co-existence of peoples who have lived on both sides of those borders for millennia. To find an agreement that works will require a level of political imagination and wisdom that very few nation-states have shown in the post-colonial world.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Why Trump’s bid to end China’s rare earth mineral monopoly may trigger a geopolitical headache