New Delhi: Rameshwar Singh heard the first boom at 10 pm while he was locking the gates to his house in Haryana’s Rajawas village, on the foothills of the Aravallis. The ground beneath his feet shuddered. The dogs started howling. For ten minutes, the booms and blasts got faster and louder.

The stone miners, who were operating in the neighhouring village, Ushmapur, some two kilometres away, were moving closer to Rajawas after a gap of eight years. For Singh and the other villagers, it was a foreshadowing of the dark times back in 2016 when his village hosted a stone mine. It had scarred the land. Groundwater also sank to alarmingly low levels. Half the villagers left their homes. The remaining contracted respiratory ailments, skin infections and other diseases, Singh said.

“The blasts from the mines used to feel like earthquakes. People had to leave their homes because the walls and the ground cracked. Nearly everyone in the village now has some form of respiratory infection.” The 68-year-old farmer blames his chronic bronchitis on the mining activities of 2016.

“We will not allow another mine to come up here,” he said.

Biologists consider the Haryana Aravallis as an ecological desert, overgrown with Prosopis and degraded in many parts.

Rajawas and hundreds of villages along the Aravalli Range are fighting a battle against rampant illegal and legal stone mines. Despite court orders, including a May 2024 Supreme Court ban on fresh mining leases in the Aravallis, the mountains are being mindlessly ravaged for stones to fuel the state’s focus on high-rise apartments, roads and office complexes. It has pitted villagers against miners, environmental activists against the Haryana government, with the police filing complaints and counter-complaints.

The irony is that Rajawas is part of the 22,400 hectares area that has been classified as protected forests. The Centre marked this portion of the hills for compensatory afforestation to make up for the loss of a million trees in the Great Nicobar, where the Narendra Modi government is undertaking a mega-infrastructure project.

There is no official record of which mountains fall under the Aravallis, even though it’s one of the oldest ranges in India, if not the world.

However, a state ministry official with the mining department told ThePrint that there are no illegal mining operations on the Haryana side of the Aravallis. The mining operation at the village near Rajawas is sanctioned. And that’s because it’s not considered part of the mountain range. There is no official record of which mountains fall under the Aravallis, even though it’s one of the oldest ranges in India, if not the world.

“The area where the new mines are allotted in the hill near Rajawas is not part of the Aravallis. It is a different hill. Its close proximity to the range could create this confusion, but we are following all rules here,” said the official who did not want to be named. Stretching from Champaner in Gujarat to Delhi, passing through Rajasthan and Haryana, the 693-km Aravalli Range acts as a groundwater recharge zone and a protective barrier against the desertification of the Delhi-NCR region.

The rampant mining activities have come at a high environmental and human cost. But even “biologists consider the Haryana Aravallis as an ecological desert, overgrown with Prosopis and degraded in many parts,” as per a 2019 survey by the Centre for Ecology Development and Research (CEDAR) and World Wide Fund (WWF) India.

Environmentalists warned that these mines are also drying up the region’s groundwater, polluting the skies. The latest report by the Haryana state government showed that Mahendragarh, the district under which Rajawas falls, has the first traces of groundwater only at a depth of 2,000 feet.

Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director (research and advocacy) at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), said that the Aravallis act as a “green fence” for the already vulnerable Delhi-NCR region.

“The Aravallis essentially acts as a sink, which filters out many greenhouse gases. It performs essential ecological services. The range is also a vital water recharge point for a region that is becoming exceedingly water-parched,” warned Roychowdhury.

Ambiguity around Aravalli

“There will be no mines here,” sarpanch of Rajawas said.

On 14 August this year, the sarpanch of Rajawas, Mohit Ghughu, received a letter from the regional officer of the Haryana Pollution Control Board in Mahendragarh district, informing him of a proposal to lease 119.5 acres near the village for a new mine. The mine will have a production capacity of 1.4 MTPA (million tonnes per annum), and there are plans to station three large stone crushers on the site.

Ghughu knew he had to stop it. Within 15 minutes, the entire village gathered in the Panchayat office to chalk out an action plan to stop the mine. The next few days were spent meeting officials from the state environment and mines departments to register their protest. The entire village stands together in this decision.

“There will be no mines here,” Ghughu said.

According to the mining department official, a detailed mineral survey was conducted in the area, but the project has yet to receive a no-objection certificate (NOC) from the environment department.

“State environment departments often use the lack of official demarcation of the range to omit hillocks and approve mining activities,” said Kailash Meena, an environmental activist who has worked extensively to stop mining on the Aravallis.

“When you don’t know what or where the Aravalli range is, how will you protect it?”

In May this year, the Supreme Court, while asking the state governments of Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi and Gujarat not to give any fresh mining leases in the Aravallis, ordered that a committee be set up to prepare a uniform definition of the Aravalli hills and range.

But until this is done, government departments are free to follow their own interpretations of which hills are part of the Aravallis. It’s why Singh’s Rajawas village is now facing the prospect of another mining project in their backyard.

The ambiguity around the clearances for mining projects does not stop here. In 2023, the forest department notified 506 acres of Aravallis falling under the Forest (Conservation) Act 1980, this was part of the 22400 hectares marked as protected forests by the Centre and subsequently by the Haryana government in a notification dated 20 June 2023. The 506 acres falling around Rajawas was a part of the total 22400 hectares that was marked as protected forests. Rephrased the sentence to make it more clear) This included khasra (land parcels in government records) numbers 91 to 124 in Rajawas. The government marked this portion of the hills for compensatory afforestation for losing a million trees in the Great Nicobar, where the Centre is undertaking a mega-infrastructure project.

“The government agencies are trying every trick to pass this project,” said Chirag Ghughu, activist.

The protected forest status does not allow construction or development activities in such areas unless separate permissions are sought from the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC). The Haryana environment department and MoEFCC officials did not respond to ThePrint’s queries about the legality of the mining project on protected forest land.

“How can the mountain next to this one be part of Aravallis, but this one isn’t? The government agencies are trying every trick to pass this project,” said Chirag Ghughu, a 28-year-old resident of Rajawas who has taken up cudgels on behalf of the other villagers.

Operating on loopholes

“The village is so close to the site that the stones would roll down and reach the village. For months, we lived inside a cloud of dust and smoke. But no one cared,” Chirag Ghughu said.

In his torn pair of slippers, Bansi, a shepherd and a local tourist guide, leads a group of tourists through the hills. As they struggle to keep up with his long strides, he stops to tell them about the rich flora and fauna around them.

“Civets, nilgai, jackal and mongoose,” Bansi said. “I have also seen a leopard here once.” Plucking leaves from an unfamiliar plant along the tracks, he claimed it has medicinal properties and is native only to the mountainous region within Haryana. Others have now vanished, he explained to the group.

During the hearing, the Supreme Court was informed that in Rajasthan alone, 31 hillocks disappeared due to rampant illegal mining. It had made a similar intervention in 2002 when mining activities were banned in the entire Aravalli region in Haryana and Rajasthan. However, subsequent inspections and surveys confirmed that illegal mining thrived in the states and had destroyed around 25 per cent of the range since 1967-1968. In 2018, a report by the Forest Survey of India (FSI) also confirmed that illegal mining was rampant in more than 3,000 sites across Aravallis in Haryana and Rajasthan.

Roychowdhury also pointed out that razing green pockets on and along the Aravallis also increases the risks of man-animal conflicts in the nearby villages.

Rajawas village’s vehement opposition comes from bitter and painful experiences. They have already experienced the repercussions of living near a stone mine. The memories are not fond.

In 2015, a stone mine was sanctioned in khasra numbers 91, 96, 97, 98, 99, 102 and 103 near Rajawas. As the land custodians, the government agencies needed the village’s approval to proceed with the project.

Back then, the government sold these mines to the villagers as a “dream project”, said Mohit Ghughu.

They were promised employment and development in exchange for allowing these mines to function. But what followed was a nightmare. They lived under a haze of smoke and dust. Trees were razed. The animals like four-horned antelope and golden jackals disappeared from the landscape. They could no longer hear the birds with the constant boom from the mine. Their wells dried up.

Seven years later, the land remains barren. Chirag Ghughu pointed to the site. It’s hard to miss the brown patch (nearly a third of the mountain) on an otherwise green stretch that looks like a mountain has been wrenched from the land. Such patches are becoming increasingly common on the Haryana side of the Aravallis. It’s barely a kilometre from Rajawas.

“The village is so close to the site that the stones would roll down and reach the village. For months, we lived inside a cloud of dust and smoke. But no one cared. We reached out to the environment and forest department and the pollution control board, but we were turned away,” alleged Chirag Ghughu.

A part of a village, closer to the mining site, resembles a ghost town. Families were forced to abandon their homes—the walls of these houses have deep fractures; the ground below them has cracked, and some structures have been outright split in half. With their homes destroyed, they left for Mahendragarh and other nearby towns.

“The impact of the blasts created these fractures. How does one live in these homes then?” Chirag Ghughu said.

According to a 2012 notification by the Haryana Mines and Geology Department, no mines should function within a “250-metre radius” from the outer periphery of the defined limits of a village, national highway, district or outer district roads. The mines near residential areas should also use only manual and mechanical crushers instead of fracturing the mountains with blasters. But none of these precautions were followed, the villagers allege. The mining official that ThePrint spoke to refused to comment on the specifics of the allegations, claiming to not be in-charge of the office during that period. He, however, said that in legally tendered mines all precautions are maintained.

Those who were left behind continue to bear the brunt to date. Many of the residents, especially senior citizens, women and children, have developed respiratory illnesses, long-term skin problems and eyesight issues.

Bansi Lal, a 75-year-old retired teacher in the village blames his severe “eyesight problem” on prolonged exposure to the coarse particles released after the mine blasts.

“After the dynamites went off, people would curl up in their houses to protect themselves from the impact. The pollution released after a mine blast is not like exposure to regular pollution. The particles are coarse, and it would feel like someone has thrown sand in your eyes,” Lal said.

Like Chirag Ghughu, the sarpanch and the rest of the village, the retired teacher is determined to not let this happen again—whatever the cost.

Threat to life

Meena, 46, who is from Rajasthan’s Neem ka Thana, has dedicated his life to protecting the Aravallis. He has faced threats to life, and spent time in jail, but hasn’t stopped. Now, he is in Rajawas to help the villagers fight the mine project.

“I started creating awareness against illegal mining on the Aravallis in 1998. I would make pamphlets and distribute them and would conduct inspections myself. When these contractors and workers started observing me, I started receiving threats,” Meena alleged.

A senior police official from the Haryana police department explained stone mining in the Aravallis operates as an organised criminal nexus. Once a site is identified as a potential mine, the mining contractors do everything from flexing money and muscle power to influencing government officials to bag the mining contracts, said the police official, who did not want to be named.

In fact, over the last few years, dozens of police complaints have been registered against the mine operators for not following basic safety guidelines.

“The most common violation that we register from a mining site now are the operations of overloaded trucks. But till about a decade back, illegal mining was a dangerous operation. Many police and government officials have been killed, beaten up and transferred out. The people involved in this business are very powerful,” the police officer said.

In 2022, a deputy superintendent of police near Haryana’s Nuh, Surendra Singh Bishnoi, was run over by a stone-laden truck when he was trying to stop activities at an illegal mine. A day after Singh’s murder, the driver of the truck was arrested, but a preliminary inquiry concluded that the accused had no connection to a ‘mining mafia’. The accused used to quarry stones on a local scale, according to statements by the police.

“In Rajasthan, just on the other side of Rajawas, some villagers were killed by local goons when they were going to file police complaints against illegal mining. A case was filed, but investigations ended at a dead end,” Meena claimed.

For the local police, cracking this nexus has been challenging. But they claim to have made progress in stunting the illegal operations to a great extent.

In Haryana, between January and June last year, fines worth Rs 21.56 lakh were slapped on suspected miners in Gurugram and Rs 40 lakh were recovered as penalties from mines in Nuh. Early this year, seven contractors were fined Rs 23 crore for illegally mining stones worth Rs 4 crore in the last 1.5 years in Rajasthan’s Neem ka Thana.

“A lot of the criminal activities around the mines have been controlled because of increased attention from the media, courts and environmentalists, though cases continue to be reported,” said the Haryana police official.

Election issue

“Unregulated mining sites are a hotbed of violations”

At Rajawas, villagers gathered to discuss the arguments against the mines ahead of a public hearing, which is mandatory before any development project is initiated near a residential area. It was initially scheduled to be held on 17 September, but was cancelled at the last moment by the government officials. The new date is yet to be communicated. In the middle of the meeting, a villager rushed in with news of a labourer’s death. He was working at the mine in neighbouring Ushmapur village. Such deaths are routine at these mines.

Nobody is surprised. “Unregulated mining sites are a hotbed of violations,” said Meena. Members of the citizens’ movement People for Aravallis have many stories of faceoffs with the ‘mining mafia’.

Neelam Ahluwalia, a former journalist and the founding member of People for Aravallis, said that if citizens were to turn their heads away, it wouldn’t be long before Delhi-NCR would turn into a desert. Her team and Meena are closely working with residents of Rajawas to file a petition against the proposed mining site.

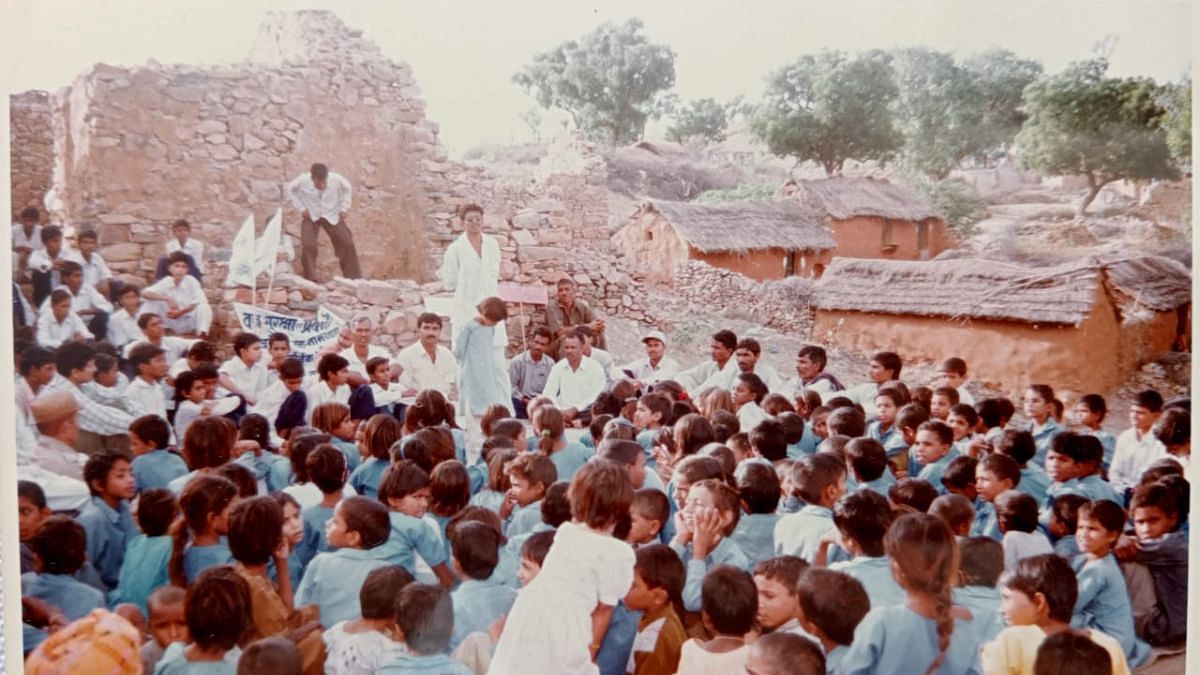

The village has been active over the last fortnight. They are preparing for the public hearing. Petitions are being drafted, placards are drawn, and residents, even from neighbouring villages, are being mobilised to protest against the upcoming mines. Children are being taught slogans demanding the protection of the hills.

The idea is to put on a united front before the mining contractors and government officials, who are already trying everything to receive a go-ahead for the project.

Residents also want to use the upcoming Haryana polls to voice their concerns. All political parties coming to the village for campaigning must detail their plan to end stone mining in the Aravallis and demarcate the range as a critical ecological zone (CEZ).

“For us, this is an election issue,” Ahluwalia said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)