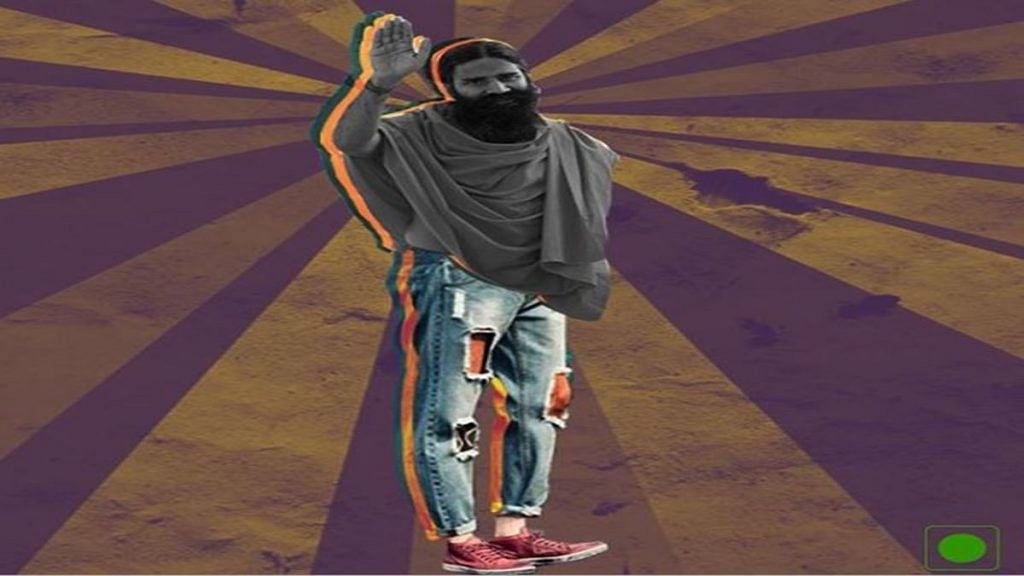

Baba Ramdev inaugurated Patanjali’s first apparel store ‘Patanjali Paridhan’ in Delhi last week. The 4,000 sq ft store sells everything from saffron langots to ripped jeans.

ThePrint asks: Can Levi’s compete with Baba Ramdev’s Patanjali sanskari ripped jeans in India?

Those who buy Levi’s are not buying the jeans but the brand, and may never wear Patanjali

Reporter

Do you dress just to cover yourself? Of course, not. Your clothes are also a means to communicate your ‘self’ to others.

Baba Ramdev’s plan to destabilise multinational brands may read like an attractive news headline, but in reality, it may not hold any relevance. A customer who wears brand Levi’s may never wear brand Patanjali. He/She is happy to pay ten times more for Levi’s because he/she is not buying the jeans but the brand. Clearly, price plays no role.

In FMCG, ‘giving a tough competition’ to Nestle and Colgate was possible because the food category is not a status symbol. Shoppers consider trust factor while buying food items which Baba Ramdev enjoyed because of his known face and achievements in yoga and herbal medicines. His formula of spending several crores on advertisements also worked well. The firm’s food business made an immediate connection with the consumer.

But the case is not same for apparels. According to a study by Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, Pune, customers give low priority to advertisements and trust while buying apparels.

Psychological satisfaction rather than utility satisfaction is expected to play a major role in apparel purchase decisions. “I may wait for discounts at Levi’s for the other three months but I will never buy Patanjali,” says a research scholar at Delhi University.

Bernard Arnault, the owner of LVMH, the most powerful group in the world selling luxury items, had said: “We sell dreams, not products.”

In price-conscious India, Patanjali will find many takers, but people who are out to buy dreams will only buy Levi’s.

Patanjali is going to kill local non-branded jeans manufacturers

Journalist

The Indian consumer no longer believes that everything that Baba Ramdev sells is ayurvedic. Patanjali is now an empire that wants to enter every market sans product quality research.

To say whether Levi’s would be able to compete with Patanjali’s sanskari jeans is an insult to the global brand which has spent a lot of hard work and money for research-based production of durable, easy-fit jeans.

Ripped, slim-fit or torn, the Indian consumer will throw it away if it becomes a rag after one wash, which doesn’t happen with Levi’s.

Consumers will continue to wear Levi’s because of its comfort, quality and fitting. Brand value and consumer habits take time to change. The only product differentiation that Patanjali is offering is of it being ‘swadeshi’ (even with torn jeans). But there are swadeshi jeans that Indians have been wearing ever since jeans became fashion.

So who will wear the Patanjali brand jeans? The desi consumers who wear cheaper, local and non-branded jeans that aren’t advertised, will now have the option of wearing Patanjali brand jeans (cheaper variants) from a glossy store.

Patanjali is basically targeting people who never chose to wear branded jeans due to its price under the garb of swadeshi and lower prices.

Patanjali is going to kill the local non-branded jeans manufacturers.

Baba Ramdev’s Patanjali Paridhan jeans aren’t actually competing with Levi’s at all

Journalist

The simple answer is no — because Baba Ramdev’s Patanjali Paridhan jeans aren’t actually competing with Levi’s at all. Just because you’re making a similar product, doesn’t mean you’re vying for space in the exact same market: price points, target demographics, marketing and brand value, among a myriad of other factors, determines the space you will occupy in a competitive marketplace — fuelled by product differentiation.

Sanskari ripped jeans stand as symbols of a swadeshi #throwback — evoking in their branding a sense of nationalistic pride for domestic, home-grown production. In the current climate, Baba Ramdev is cool for a vast number of people led by majoritarian thinking. Levi’s, meanwhile, continues to be reserved for those still nursing a colonial hangover. Like its high price point, Levi’s sits at a shelf high enough to be just of out of reach for middle-class aspirations, but low enough to be scoffed at by brands like Gucci.

There was a time when Levi’s enjoyed one of the highest brand recall values — synonymous with ‘jeans’ altogether. But times are changing, and as the Indian market opened up to a flurry of affordable, yet fashionable, apparel stores from around the world, the era of Levi’s soon faded into the background. The consumer emerges victorious, with a plethora of choices ranging from H&M, Zara, Forever 21, Wrangler, yes Levi’s, to brands like Patanjali. Jeans aren’t FMCG goods – people tend to care more about what people think about the jeans they wear than the toothpaste they use.

Patanjali’s impact on Levi’s will depend upon ideological competition between capitalism and nationalism

Journalist

The impact of Ramdev’s “sanskari” jeans on Levi’s India business will depend upon the competition between two ideological forces: Capitalism and nationalism.

Famous Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter outlined three strategies which firms adopt to compete in the marketplace: Cost leadership, differentiation and focus. A firm that wants cost leadership will price its products at or slightly below market price level, maintain decent quality and cut costs substantially. A differentiator’s product, on the other hand, will have a unique aspect to it for which the differentiator generally charges a premium over normal market price.

In the case of Levis, it’s clear that it’s consumer base isn’t very price sensitive. Jeans of comparable quality from various other brands are available at much cheaper prices but that hasn’t eroded Levi’s market share. The capitalistic urge to appear different, to spend more because you can, is difficult to contain.

“Sanskari” jeans, however, has a differentiating aspect to it at no extra market premium. It is swadeshi. For Patanjali to compete with Levi’s, it needs to stress upon primordial nationalism. In that case, some of Levi’s consumer base may shift towards Patanjali. Although in the long run, I don’t see nationalism overcoming people’s capitalistic impulses.

Also, there is another aspect to this debate. While Levi’s as a premium brand won’t get affected, other low-priced brands most certainly will. Patanjali, with tacit government support, will not only emerge as a low-priced cost leader but will also be a differentiator. It’s an enviable scenario for any market player.

By Neera Majumdar, journalist at ThePrint.