Mumbai: In 1999, when Sharad Pawar formed his Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) after severing ties with the Congress, he wanted the charkha (spinning wheel) as its symbol to reflect the party’s Gandhian ideological roots.

When the Election Commission (EC) rejected that request, the party chose a clock as its symbol.

The NCP adopted the party’s constitution and appointed office-bearers for the very first time on 17 June, 1999. The meeting for that, at Mumbai’s Shanmukhananda auditorium, had started at 10.10 am.

And so, the clock in the party’s symbol always shows the time as 10.10.

Twenty-four years on, the NCP has been a lot like its symbol — frozen in time, at least as far as its electoral performance is concerned.

The NCP’s electoral presence in its home turf of Maharashtra and the Lok Sabha is almost the same as it was in the party’s initial years.

The NCP’s national footprint has only shrunk and in Maharashtra, it hasn’t been able to expand beyond its bastions of western Maharashtra and Marathwada.

Moreover, while it has built a strong file of second-rung leadership, it is still overdependent on founder Sharad Pawar for its identity, as was evident from the huge protests by party workers over Pawar’s announcement that he was resigning as NCP chief last month.

The 82-year-old had to eventually take his decision back.

And while the NCP is perhaps the most prominent opposition party in Maharashtra as of today, it is more on account of the weakening of other parties rather than the growth of the NCP.

The Congress’ footprint has been shrinking in Maharashtra, with the party’s vote share having plummeted to 15.87 per cent in 2019 from 27.2 per cent in 1999. The Shiv Sena is also split into two, with both factions being on opposite sides of the spectrum.

“As a party, the NCP is very active. Some or the other party activity is always going on, but this has not led to the development of a pan-Maharashtra presence. That’s why the NCP has not been able to cross its peak of 71 assembly seats in the state that it got in 2004,” Hemant Desai, political analyst, told ThePrint.

Also Read: Bargaining within NCP? Overtures to BJP? The curious case of Ajit Pawar’s political moves

Range-bound electoral performance

Speaking to ThePrint, Nitin Birmal, associate professor at Pune’s Dr Ambedkar College of Arts & Commerce, said: “Since its origin, the NCP has mostly been seen as a Maratha party. Some support base that the party had in the Other Backward Community in the beginning has now dwindled. And the caste factor has limited the NCP’s geographical expansion.”

“Moreover, the party’s leaders have close links with the state’s cooperative sector, which has been especially strong in western Maharashtra and parts of Marathwada, and so the party’s influence is largely in these parts,” he added.

The NCP contested its first Lok Sabha and state assembly election the same year that it was formed — 1999.

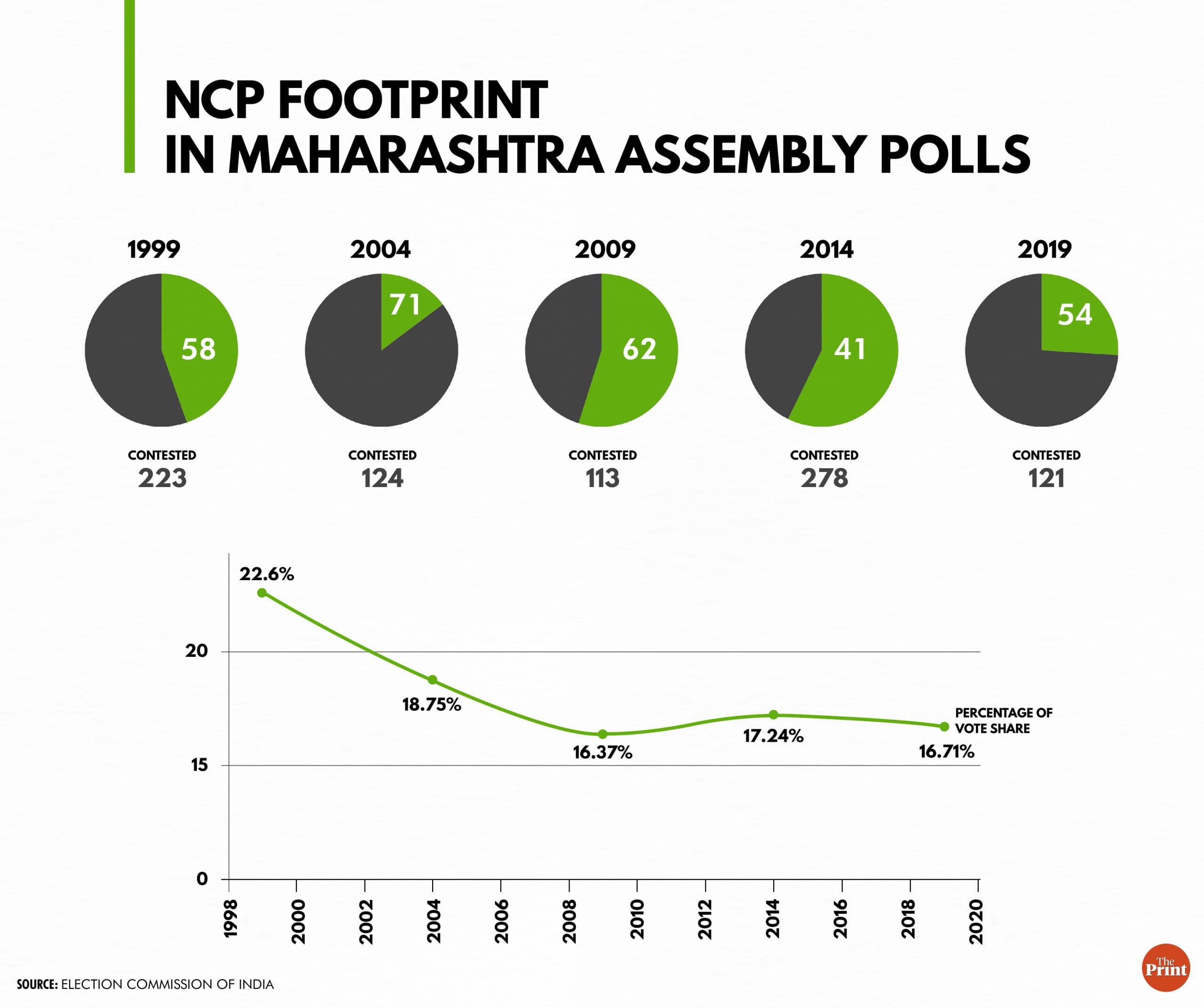

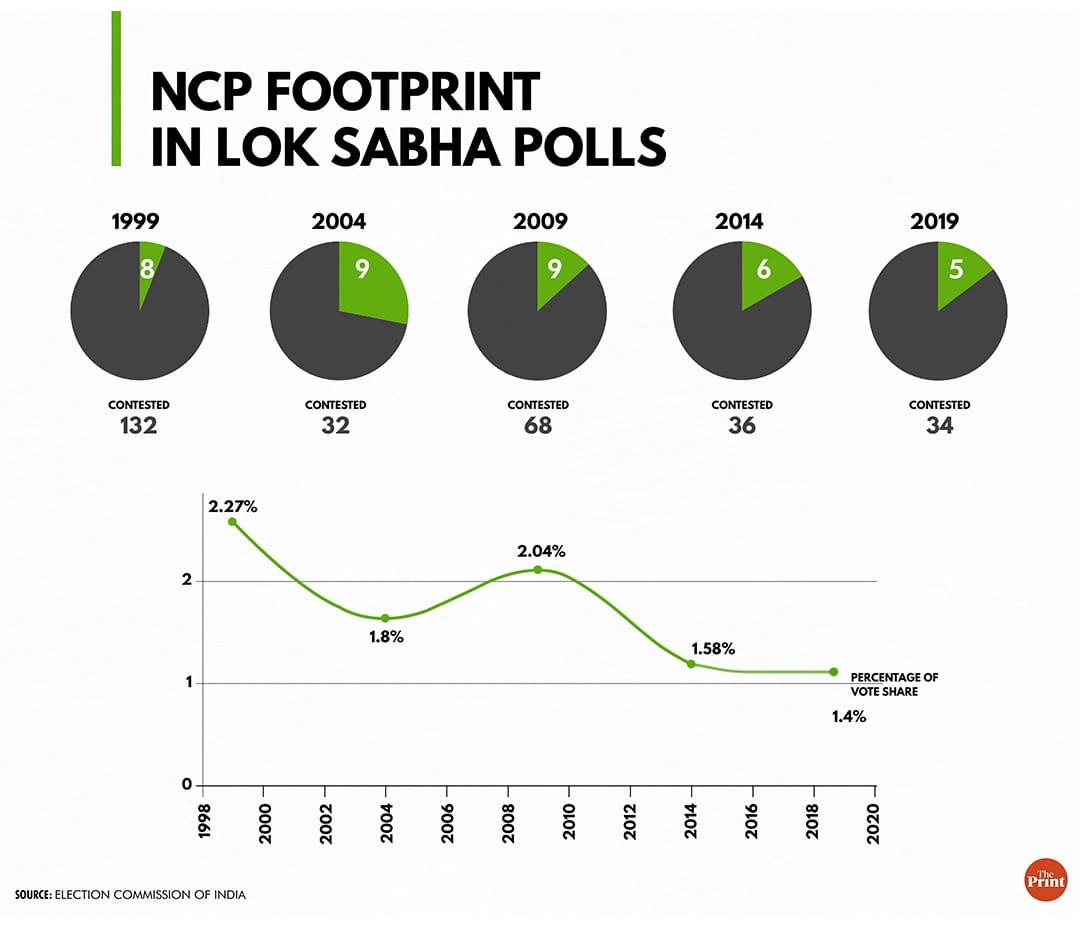

According to EC data, in the Lok Sabha, the party won eight seats with a 2.27 per cent vote share, while in the Maharashtra assembly, it won 58 seats with a 22.6 per cent vote share.

While the party’s vote share has narrowed over the years, the number of seats it has been winning has mostly remained in the range of 41 to 71 in the state assembly and five to nine in the Lok Sabha.

The NCP was recognised as a national party in January 2000 as it held “state-party status” in Maharashtra, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Manipur and Nagaland.

In April this year, though, the Election Commission took away the NCP’s national status after conducting a review and concluding that the party no longer satisfied the conditions for state-party status in Arunachal, Meghalaya and Manipur.

Desai said: “The NCP has spent more than 17 of the 24 years of its existence being in power. Its politics has been framed by being in power. And when it has been in the Opposition, it has faced criticism of not being a strong enough Opposition, of going soft on the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).”

‘The Maratha party’

NCP leaders ThePrint spoke to admitted that despite constant activities and programmes involving party workers and field visits by their senior leadership, the party has not been able to, quite literally, push boundaries.

Leaders pointed to how the NCP hadn’t been able to reclaim its space in Maharashtra’s Konkan region after some tall leaders, such as Uday Samant, Deepak Kesarkar and Bhaskar Jadhav, all formerly with the NCP, shifted loyalties to the undivided Shiv Sena.

Samant and Kesarkar quit the NCP before the 2014 assembly polls, while Jadhav left before the 2019 state election. Both Samant and Kesarkar were part of the rebellion of Shiv Sena MLAs led by Eknath Shinde last year, and are now ministers in the Shinde-led state government.

The NCP leaders also pointed to how regions such as Vidarbha and Mumbai have been elusive for the party.

One reason, they say, is that the NCP has not been able to shed its initial “Maratha party” tag, while the other reason is that successive state leaderships failed to take up programmes to popularise the NCP and expand its base outside its core regions.

“That is changing though. For the past four or five years, we have had robust membership drives, monthly interactions with karyakartas and regular tours across Maharashtra by the state president (Jayant Patil),” an NCP functionary told ThePrint.

Another Mumbai-based NCP leader recalled how Pawar, shocked by the deaths due to a stampede on a foot overbridge at Mumbai’s Elphinstone Road Station (now known as Prabhadevi) in 2017, had admitted to a few leaders that the party should have taken up issues of Mumbai more persistently.

“I remember him saying ‘apla Mumbaikade durlaksha jhala’ (we ignored Mumbai),” the NCP leader said.

‘Pawar brand of politics a bit too cultured’

Earlier this week, speaking to reporters, MLA Rohit Pawar, Sharad Pawar’s grandnephew, expressed frustration with senior NCP leaders for not speaking up when political rivals make allegations against their party chief.

Many in the NCP, including some from the very senior leadership, share the same frustration, party sources told ThePrint.

But, ignoring political allegations instead of responding to them or negating them, and even keeping political rivals close is, after all, a part of the Pawar brand of politics, it is said.

A former NCP leader who defected to another party told ThePrint: “Even today, if any of the leaders who have quit the party want to meet Pawarsaheb, he will not say no. He will not allow any of his party leaders to unnecessarily raise criticism against us.”

“The BJP keeps criticising him (Pawar), and yet he goes and meets chief minister Shinde to invite him for a programme. He likes to keep his politics civil, but sometimes it sends a different message to the public,” the leader added.

A senior NCP functionary pointed out that Pawar’s politics is “a bit too cultured” for the times.

“Pawarsaheb prefers restraint, his politics is very cultured. So, our leaders haven’t been groomed with the spirit of aggressively responding to allegations. This sometimes creates a negative perception about Pawarsaheb, creating a cloud of doubts about his political intentions. And this affects the party’s prospects,” he said.

Birmal, however, sees the flatlines in NCP’s political base and performance as its single largest achievement in 24 years.

Maharashtra has a multi-party system of politics with little scope for extreme regionalism — unlike in some southern states — for any party to expand beyond a point, he said.

“Western Maharashtra has rapidly urbanised in the past two decades, and the NCP, despite having a rural image and being seen as a farmers’ party, has managed to retain its hold on the region. The BJP’s aggressive expansion has eroded almost every party’s base, but the NCP has by and large protected its turf,” Birmal pointed out.

“Retaining what the party had is an achievement in itself,” he added.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Loyalty, boundaries, revolt — what shapes the ‘Pawar brand of politics’ and where it’s headed