Charaka, in his medical treatise Charaka-samhita, speaks of the ‘Tritiya Prakriti’ or the third naturally occurring state of being. Words for this state include kliba (impotent, sterile), napunsak (not male) and kinnara (not quite male) in Sanskrit; pedi (crossdresser) in Tamil; and pandaka (effeminate homosexual) in Pali. These terms can be confusing as they refer to biology (genitalia), psychology (sexual feelings), behaviour (sexual acts) as well as social expression (clothing and public behaviour).

In the Maha-bhasya, composed by Patanjali in Sanskrit 2,300 years ago, sexuality is seen in physical, tangible terms—a man is one who has hair all over his body, a woman is one with breasts and long hair, and the one who is neither male nor female is the ‘napunsak’. In Buddhist literature, greater importance is given to behaviour rather than to biological markings, so we hear of men who have sex with men, or women who behave like men, all of whom are forbidden to join the monastic order.

In Jain scriptures, nearly 1,500 years ago, we find a far more refined understanding of gender and sexuality, with differentiation made between the physical (dravya-purush) and the psychological (bhav-purush), i.e. anatomy and psychology.

Also read: Surat’s diamond heiress is a 9-yr-old Jain nun who now walks ‘bubble-like sansaar’. Barefoot

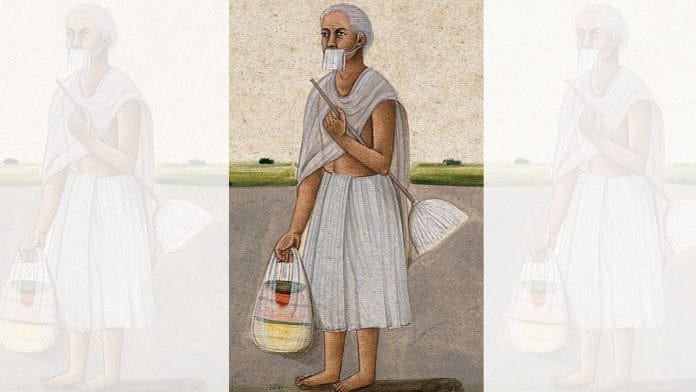

Ancient monks recognized that the body can be male (purush), female (stri) or queer (napunsak). Women were seen as temptation for men and female biology as an obstacle to spiritual progress. Nuns were told that they were one step lower than men in the spiritual ladder. To attain the highest goal, they needed the male biology that allows one to control and even reverse the flow of male sexual fluid (virya).

Attraction for females was known as purush-veda, attraction for males was called stri-veda, and attraction that was not so clear was called napunsak-veda. Of these, the male body which was attracted towards females (male heterosexual) was privileged and seen as most suitable for the monastic path. Jain monks observed that sexual desire for men (purush-veda) is like a forest fire; for women (stri-veda) it is like a dung fire, i.e. most manageable; and desire for queer people (napunsakveda) is like a settlement fire, i.e. the most intense. This was the reason why queer people were prevented from becoming monks, so that they don’t upset the monastic order.

Further, in some Jain texts the classification is based on the object of attraction—male, female or queer. This can be seen in all three genders. There are also references to socialization, with the purush-napunsak being differentiated from the napunsak, meaning the masculine queer from the feminine queer. There are also references to active (padisevati) and passive (padisevavati) homosexual acts in Buddhist literature. All these ideas emerged around 1,500 years ago and were explored in the following centuries.

The purpose, however, was very different from modern gender studies. The latter seek to create an ideal world where all choices are permitted, respected, celebrated and there is no imposition of patriarchal heteronormative structures. Ancient Indian gender studies were designed to appreciate the diversity of nature (anekanta-vada), as well as to identify those who could become monks, outgrow sexual desire and liberate themselves from all karma. This must be further distinguished from Christian attitudes that saw sex as sinful, and Islamic attitudes that sought permission from prophets to approve a particular sexual choice.

This excerpt has been taken from Devdutt Pattanaik’s ‘Bahubali: 63 Insights into Jainism’ with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt has been taken from Devdutt Pattanaik’s ‘Bahubali: 63 Insights into Jainism’ with permission from HarperCollins India.