Bihar is the victim again of much pity and some sniggers as an example of a state that abolished its APMC Act and apparently ruined its agriculture. The facts, as we showed in #CutTheClutter Episode 634, are quite different. In fact, we’ve been picking up the signs of positive change in Bihar since 2005, when the Nitish Kumar epoch began. It also taught about the ‘Underwear Index of Economics & Politics’.

I have learnt over the years that if you really want to know what is going on in our country, what is changing and how, who is in or out, how we are feeling about ourselves at any moment and what ideas are being embraced or junked, then hit the road. And keep your eye on the walls as you drive past the countryside.

What you see written or painted on the walls usually gives you a better idea of what is going on than any survey, opinion poll or talking head could.

Because, in our countryside, the walls are the most popular and democratic mass medium, and the best mirror of the current state of economics and politics.

Here is how it works. Depending on how prosperous or backward a region is, you can find writings on the wall selling just about anything — ranging from the latest cars and immigration to “Kanada” in Punjab, to fertilisers and tractors in coastal Andhra, to little more than snuff or anti-itch creams in the poorest districts of east-central tribal India.

In Bihar, where I’ve been travelling during election time since 1989, you would often have seen nothing, because people either had no surplus to buy anything but basic food, or because there were no pucca walls. I had reported the sighting of the first such writings from my travels in the two elections held in 2005 — selling what else but private education, mostly English-medium schools and coaching centres for engineering and medical college admissions.

We had noted then that Nitish Kumar’s message, “it is time to fill your pen with ink” (as against Lalu’s usual “it’s time again to season your lathis in oil”), seemed to reflect better the changing mood in Bihar — from caste empowerment to aspiration for education and a better life.

With his emphatic victory in 2005, Nitish proved that writings on the wall do not lie. As results poured in on 24 November 2010, he proved that fact to us again by winning a second, bigger mandate. Particularly as none of his challengers were able to either match his promise of development, or challenge his track record. That election, quite frankly, looked like a done deal more than any other in recent memory — except, probably, the Rajiv Gandhi landslide of 1984.

It was written on the walls of Bihar, a fascinating story, in an intriguing new script. Don’t jump if I say its alphabet was branded underwear.

You drove two-and-a-half thousand kilometres through Bihar’s political heartland, generally south-east from Patna, criss-crossing the Ganga, through Begusarai, Bhagalpur, Banka and right up to the border of Jharkhand — and you found colour on the once-mostly blank walls of Bihar as you had never imagined.

I call the script intriguing because all that the walls of Bihar seemed to be selling to you was branded underwear. Rupa, Lux Cozi, Amul Macho, all the top desi underwear brands were there, selling the comfort, good looks and feel — and of course sex appeal — from walls, hoardings and signboards, hanging from electricity poles and trees.

All the naughty tag-lines that you might remember from TV ads that were banned for being in bad taste were in evidence, including one featuring briefs with a tell-tale bulge, saying “andar fit, bahar hit”. Obviously on the ball, Rupa, probably our number one underwear company, produced a new brand: ‘Jon O-Bama’. Barack Obama was recently in India, and so, was popular.

Now, naughtiness apart, did we read a message of socio-economic change on Bihar’s walls? And if so, could politics be immune from it? This was a state with widespread starvation, utter misery, and where a large majority had nothing left to buy anything beyond basic clothing to cover their bodies. Somebody was now trying to sell comfort, good looks, even sex appeal of branded underwear here? Did that mean something had changed? Never underestimate the ability of the Indian FMCG marketer to sniff out a new emerging market or consumer need. Which is exactly what the underwear people did in Bihar.

If a state of eight crore people (at the time) was being lifted from utter poverty to at least a level at which many could aspire to a better quality of life than mere survival, you would expect tens of millions to invest in basic comfort — like decent, knit underclothing.

Socio-economic change inevitably finds political expression, and with the results of the 2010 election, you could say that it was the first time in the history of democracy when branded underwear predicted an election better and earlier than any psephologists.

Also read: Punjab’s frustration & anger is rooted in its steep decline, now visible in farmers’ protests

A “kachha-baniyan” theory of political change? Can we get more facetious than that? So, if you’d prefer something more staid or old-fashioned, let’s look at plastic chappals and bicycles. One of the things that caught your attention, and made you feel so humble when you travelled in a Bihar election in the past, was the large numbers of people who came to campaign rallies barefoot.

At five election rallies in 2010, addressed by Sonia, Rahul, Nitish, Advani and Lalu, at Begusarai, Bacharia, Cheria-Bariarpur, Munger and Tarapur, respectively, some of us stooped really low to make a quick count of bare feet. I found only four pairs in Sonia’s rally, which was bigger than any you had seen the Congress hold in Bihar in decades.

One old woman said she broke one chappal on the way; two young girls said their mothers told them to leave chappals at home or they might lose them in the crowd, and only one said she didn’t have any. In Nitish’s rally, there were a few more, maybe about 5 per cent — it was evidently a much poorer crowd from the more deprived and backward sections and castes, and much more animated.

But so few bare feet in the most backward regions of Bihar should’ve convinced you of the change, if the underwear on the wall didn’t. Bihar was in the midst of a virtuous transition, enjoying a sweet turn it had even stopped dreaming of. And it showed on its proudest and even politically the most significant new asset, its beautifully tarred roads. Not just the highways, but even the rural roads built under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana. Like many other chief ministers, Nitish saw road-building as the easiest picking in a state that, to any serious leader, would look like an orchard of low-hanging fruit.

Lalu had to blame himself because Nitish’s success with road-building devastated him in the 2010 election. Lalu it was who made the state of roads into a telling political metaphor in Bihar. He first dismissed them as a luxury for the rich with cars. Then, he promised to build roads as “chikna” (smooth) as “Hema Malini’s cheeks”. But he just wasted his time and his state’s money till his people decided to check out an alternative in Nitish. And a vast majority of them thought they made the right choice in the second election of 2005.

There are moments in my life when I so love my job. Usually, these are selfish moments of petty journalistic conquest, like a scoop in the paper, an interview with somebody I may have adored, or just the hack’s privilege of being in a newsy place: Assam in the year of Nellie and other tragedies, 1983; Amritsar, Operation Bluestar, 1984 and in New Delhi’s great killings of the Sikhs in the same year; the Tiananmen Square massacre, 1989; the former Soviet bloc, as it unravelled, in 1990; the Al Rashid Hotel in Baghdad during the bombings of the first Gulf War, 1991; Kabul as the mujahideen won the first — and “good” — jihad against Najibullah in 1993; and so on. But these were all moments of sadness and tragedy, and only a heartless reporter would look back on them with any feeling of accomplishment, if not joy.

Also read: Modi govt gave an unwanted gift to farmers. Now it can’t even handle rejection

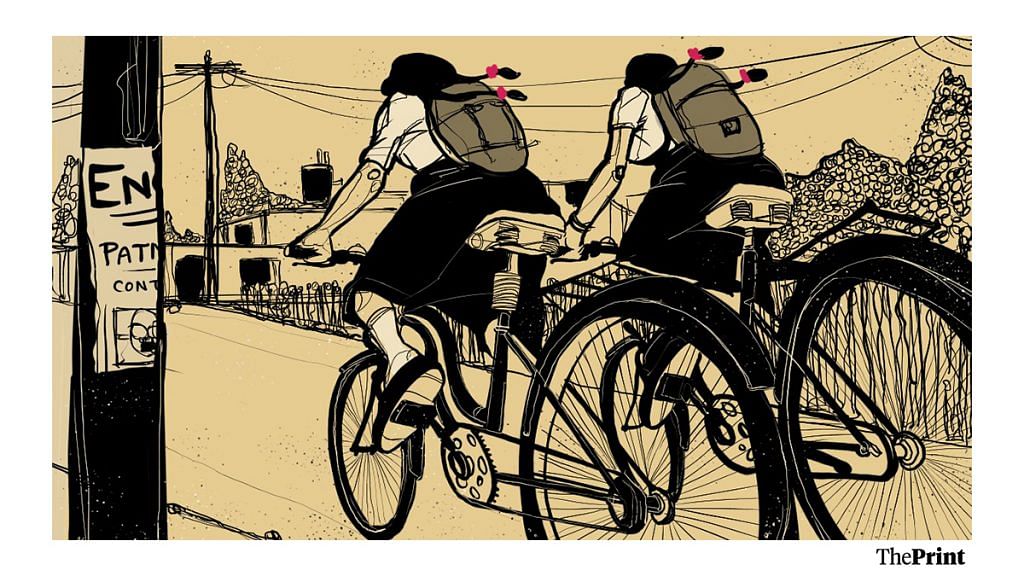

But in Bihar, there was a sight to cherish that made me love my job as well. It would light up your eyes, cheer your saddest, darkest hour, put a bounce in your step and, most of all, convince you once again that there was hope even for the worst-governed, the most neglected parts of our country — young girls, dozens and dozens and scores and scores of them, mostly in school uniforms, riding bicycles on the state’s new roads.

Don’t miss the link between the roads, bicycles, uniforms, and the results of 24 November 2010. Nitish decided to attack the problem of low enrolment and large dropout rates for his state’s girls by offering a free bicycle to any girl moving to class nine. Four lakh bicycles had been distributed by then, and you already saw a revolution of sorts on the wheels. Meanwhile, high school enrolment for women had trebled.

If you wanted convincing beyond the writings on the wall, the underwear ads, you looked at people’s feet, at the roads, at the bicycles and the proudly smiling faces of some of India’s poorest young women riding them. You would see change, change for the better, and change brought about entirely through old-fashioned democratic politics that we, the urban well-heeled, so love to denounce as India’s curse.

(This article was first published in November 2010)

Also read: What Modi govt proposed but farmers rejected — assurance on MSP, 7 amendments to new laws