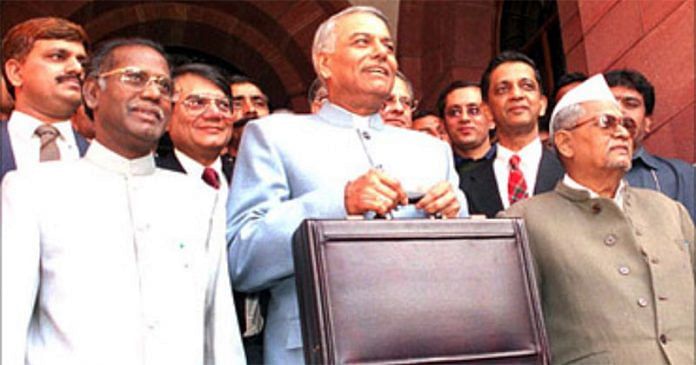

After wondering for an entire week why poor Yashwant Sinha got such bad press on his budget, I found the answer last week, in the middle of the night, on board Air India 443, which arrived from Singapore on the dot at 1.20 am. Now it stood waiting, its doors open to let in fresh air, Kandahar style.

It was waiting, for half an hour, for the stepladder which had obviously not been positioned anywhere close to the parking bay. Weary passengers and crew paced up and down, and celebrated as the stepladder arrived, mounted on a creaky, 1960s vintage Tata truck. But the driver wouldn’t couple the ladder. His reason was pretty sound. Nobody had remembered to put the chocks to block the wheels of the parked aircraft. The driver wouldn’t risk coupling the ladder with an aircraft with unsecured wheels. So another scramble started, this time for the chocks as none had been positioned close to the plane’s parking bay….

It is a long story of a painful night with a bit of Kafka, a bit of Greek tragedy, a bit of magic realism even. And I intend to tell it fully and also explain why I think its lesson is that Yashwant Sinha, and other committed reformers like him, get it all so wrong simply because they fail to convince consumers like you and me, the types trapped in AI 443 and another public sector monstrosity that passes for an international airport in Mumbai, why reform will change our lives for the better. We are told, instead, that reform and privatisation will produce a few thousand crores with which the government could pay its debts. Who cares? You wouldn’t, if after having sweated, waiting for the stepladder, you now had to wage a lonely, hopeless battle for a baggage cart.

This was particularly rough on the woman in black sweatshirt and jeans, travelling by herself and now on the verge of tears. “I will not, I will not, no matter what happens, push and shove for a baggage cart,” she pleaded before bemused airport officials. “Then how else do you expect to find one?” she was asked.

“But nowhere in the world do you have to fight for a baggage trolley. That’s minimum a passenger needs on landing. And there isn’t even a glass of water to drink here,” she was now screaming.

She only got some sympathetic glances, a chivalrous offer by somebody to do the pushing and shoving on her behalf instead, a few official sniggers and finally an excited tip-off. There, run, they are wheeling in seven more carts. You have a real chance…

But what help would it be to even find a cart if now, more than an hour after the flight had landed, there is no sign of baggage on the belt. Bored passengers squat on it, since there is no other place to sit. Even the duty-free shop is inaccessible – uniquely – before the immigration area, so there is no place to even kill time.

Then, a friendly, but utterly helpless Air India official explained the reason why baggage takes so long to arrive at Sahar. The new terminal is designed so poorly that pillars block the way of the baggage tractors. So only one can get in at a time and if two or three flights arrive close to each other, which is the case every night in Mumbai, your baggage could sit for a long time on a tractor in this queue. “Don’t blame us,” said the Air India staffer, “please go ask the Airports Authority if they’ve been employing college dropouts as architects and designers.”

Also read: Off The Cuff with Yashwant Sinha

By this time we were in pretty good company as even the crew of our flight waited along with the passengers for the baggage and finally, at 2.55 am, exactly an hour and 35 minutes after the aircraft doors had opened, the conveyor belt screeched and rattled musically to our ears. But the baggage that came out first didn’t belong to any of the passengers, not even the business class types. All you saw were several odd-shaped plastic and tarpaulin bags which were quietly carried away by uniformed porters, the most efficient people on duty. These, another cynical official explained, were consignments for courier companies. “They are networked rather well here, you know, so their consignment sometimes gets priority over first class baggage,” we were told. Our bags did arrive, some time later. But the story of the night is not over yet.

“What exactly are you carrying in your bags?” asked the hound from customs as several of us walked through the green channel.

“Personal effects,” I said.

“What else are you carrying?” he persisted.

“Well, if I am walking through the green channel, it means I am stating that I am carrying nothing dutiable. So if you still have doubts, please check my bags,” I suggested.

“Oh, just put them on the x-ray machine,” he said. The bags, in his book, also included my solitary lounge suit that I was carrying on my shoulder, in a transparent, plastic garment cover. But I swallowed my pride and waited at the other end. The woman at the monitor was too bored to even look at what was passing through the scanner. But she wouldn’t suffer fools like me so easily.

“See what you have done? Your baggage has blocked our machine,” she poured contempt as I extricated my suit from the x-ray belt.

“How is it my fault?” I asked.

“See how stupidly you put your baggage there. How can we work with passengers like you?”

One more kick in the pants and I escaped from the great public sector/Government of India trap that is supposedly our biggest international airport, the real Gateway to India. Behind me, others were being insulted even more brutally. No wonder, just a while back, the woman in the black sweatshirt was telling her family on the mobile phone: “I am fine, even if there is no baggage cart. But let me tell you, if you wish to feel like a respectable, dignified Indian, please go to China. Here you can’t even feel human.”

What is there in this story for Yashwant Sinha who is now being pilloried for presenting a budget so dreary that it wiped nearly Rs 70,000 crore from the BSE market cap and so status quoist despite his promise of reducing the government’s holdings to a minority in key PSUs? The central lesson is that people like us, who survive the AI 443 kind of ordeal in various aspects of our lives in all parts of the country all the time, in the hands of a system where crucial services are run by the pampered, almighty PSUs, need to be told why privatisation and disinvestment are good for us.

How do we care if it would help Sinha pay off some of his debts? But if it means we will have cleaner, less corrupt airports, better airlines, more efficient banks, safer railways and, generally, more competition and choice of our marketplace, we will all be on his side. The reason he, and other reformers, are shy of saying so is that if there is one thing governments are scared of, it is their own employees. But this notion is stale, stupid and suicidal. Even the staff of the PSUs that have been exposed to competition have changed for the better, and dramatically so. State Bank of India, Unit Trust of India and Indian Airlines are prime examples of this. So if he wants to be remembered as a genuine, radical reformer rather than a mere tinker of conventional wisdom, Sinha has to learn this crucial lesson. This is the bullet he needs to bite.

Postscript: I did not have to push and shove, as an Air India employee marked me out as one of her airline’s privileged flyers by presenting me with a baggage cart.

Also read: Yashwant Sinha: My problems with Sangh Parivar increased when I became BJP finance minister