The latest turn in the nuclear issue, with India’s top scientists going public with their concerns and insecurities, has brought back the memory of a delicious little story from my reporting years. A young IAS officer, and one particularly gifted with a spectacular sense of humour, once told me of his first week on deputation with the Department of Atomic Energy. The chairman, he said, told him plainly that DAE was a place for scientists. It did not particularly need IAS officers, except one, to answer Parliament questions. That was to be one of his major responsibilities he said, and then set out the principles. Never lie to Parliament, he said, but never tell a straight truth. They can’t handle it. So, the principle is, when they ask you your name, tell them your date of birth.

When he told me the story, we laughed and promised to exchange notes at a later date on whether this worked. I met my idealistic civil servant friend sometime later and asked how was it going at the DAE and whether the principle laid down for him in dealing with Parliament worked any more effectively than the department’s fits-and-starts reactors.

He said it worked brilliantly, and explained how. There was this MP, for example, who wanted to know the per unit cost of nuclear power produced in India compared with other sources. The answer could be five words. But it was five pages long and, in the words of my very pleased friend, worth five rounds of applause in Parliament. I do not have to repeat the five pages, but the answer went something like this: India’s nuclear programme is entirely for peaceful purposes but because it’s been the victim of sanctions and discrimination, our scientists have had to develop everything, every little technology, every nut and bolt, indigeneously (first applause). We are proud of our scientists for setting up sophisticated power plants and carrying out a peaceful explosion (applause II). Because of restrictions on uranium exports to India, our scientists are working on an entirely indigeneous technology of pressurised heavy water reactors (PHWR) (applause III). Because of the technological challenges involved, the development has been delayed, but you will soon see our very own swadeshi plants at Narora and Kalpakkam (applause IV). And finally, because of the uniqueness of the technologies our scientists are developing, it is not possible to calculate the cost per unit of the power produced yet, or to make comparisons with other means of power production, or with nuclear plants overseas (applause V).

Talk to anybody who has dealt with our nuclear establishment, and he will tell you some story like this. Sure enough, nobody would be disrespectful, or not proud of DAE’s achievements, particularly on the weapons front, but nobody would deny that for nearly half a century, this has been perhaps the most secretive, unaccountable, protected and pampered scientific establishment in any democracy. The ministry has mostly been controlled directly by the prime minister of the day, the DAE chief has enjoyed high official status (not answerable, mostly, to anybody but to the PM) and super-high access. And pampering has extended, most importantly, to protecting DAE from the prying eyes of auditors and other institutions of oversight. Our MPs, in any case, have never shown the intellect, diligence, or courage to raise real questions or seek real answers to them.

Also read: Modi versus Modi

India’s nuclear programme was set up by Homi Bhabha under Nehru’s paternal care as primarily a civilian programme that acquired a strategic dimension as the Chinese moved closer to their own nukes. As with most civilian nuclear programmes in developing countries, some of India’s first reactors were imported. But imports and access to foreign technologies began drying up as India’s nuclear weapon ambitions became clearer, especially after the first nuclear test in May 1974. The political and scientific leadership accepted the price that India’s civilian nuclear development had to pay because of the strategic imperative.

Initially, the military dimension may have come as an add-on to a largely civilian programme. But now, with two hostile nuclear armed neighbours, a credible, minimum deterrent was a necessity that superceded all else. So no problem if nuclear power generation targets were years behind schedule, if much of India’s nuclear research was no longer peer-reviewed, and if frequent reports of radiation leakages and risks were brushed under the carpet. We needed, first of all, a bomb, not just a scientific device but a deliverable weapon, in large enough numbers to provide credible deterrence even in a second strike against Pakistan (mainly) but also China, and then a delivery vehicle.

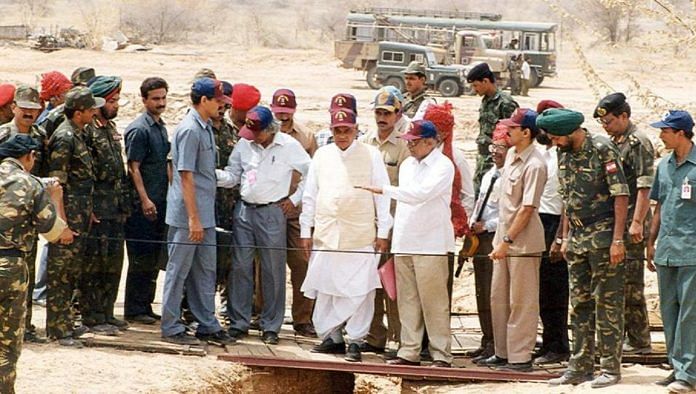

Thanks to the selfless work of hundreds of nuclear and rocket scientists, working on minuscule government salaries, and denied international academic review or appreciation, India acquired both, and Pokharan-II was a public announcement of that fact. Is it any surprise then that it was post-Pokharan that the NDA government began a conscious, deliberate and determined campaign (scripted quite brilliantly by Jaswant Singh and Brajesh Mishra) to pull India out of this nuclear apartheid of a half century. A minimum credible deterrence was in place. Enough capacity was available to be kept in the strategic domain to replenish or increase the arsenal in years to come. So the challenge now was to make legit, what had been achieved through so much secrecy and some subterfuge. The July 18 Manmohan-Bush agreement was one more logical step in that campaign.

In the days I used to frequent the strategic conference circuit, I had a favourite question to wake up audiences of bored counter-proliferationists in post-lunch sessions. How come most of India’s nuclear hawks are from the South? And then I would suggest, darkly, that this is some kind of a southern plot to get the Punjabis on both sides of the border to incinerate each other so Tam Brahms could rule all of India! Following one such session at Salzburg in 1994, General K. Sundarji (one of the leaders of the southern nuclear hawk-pack) took me out for a walk. Everything is now ready, he said. India needs just a couple of years and then all this subterfuge will end. The challenge then will be to integrate India’s nuclear establishment with the civilian world, of restoring it back to its role of developing power and other civil technologies.

Of course, he said, it will be tough, because everybody has begun to enjoy the challenge, as well as the protection of the sanctions. Even tougher, he said, will be to convince the Indian political establishment, media and public opinion that “more is not needed when less is enough”. It was an expression he was to use in some of his subsequent writings, as if initiating that process of moulding public opinion. A pity he is not around today to say this even more forcefully. He could have contributed a great deal to countering the suspicion and insecurities pushed forward by a few so-called experts and members of the nuclear establishment still heady on a cocktail of nostalgia laced liberally with Pokharan II testosterone.

The latest turn in our nuclear policy is the Indo-US engagement. By helping India’s still shy and suspicious nuclear establishment towards its much-deserved coming-out party, Manmohan Singh is only taking to its logical conclusion a process initiated by Nehru, nurtured by Indira and then strengthened by Vajpayee. Just because it might involve a handshake with Bush or just because some of our scientists suddenly show stage-fright, is no reason why India should lose this opportunity. With a minimum credible deterrent in place, and future capability intact, there is no percentage for India to keep its nuclear establishment in the same shadowy domain as North Korea or Pakistan. After four decades of ambiguity we took the big risk in Pokharan II and it worked. This is the time to enjoy its rewards. This is a moment of confident re-assertion rather than insecurity because, as the late Sundarji had put it so tellingly, in the business of nukes, more is not necessary when less is enough.

Also read: A new, clear doctrine