Bengaluru: ISRO’s ambitious human spaceflight programme is headed by a woman, V.R. Lalithambika. In 2018, Canadian physicist Donna Strickland became the first woman in 55 years to win the Nobel for physics (she shared it with Frenchman Gérard Mourou) and only the third to do so in history.

It has been a long and arduous journey, but more and more women are defying centuries-old stereotypes and shackles to emerge as pioneers in different fields of science.

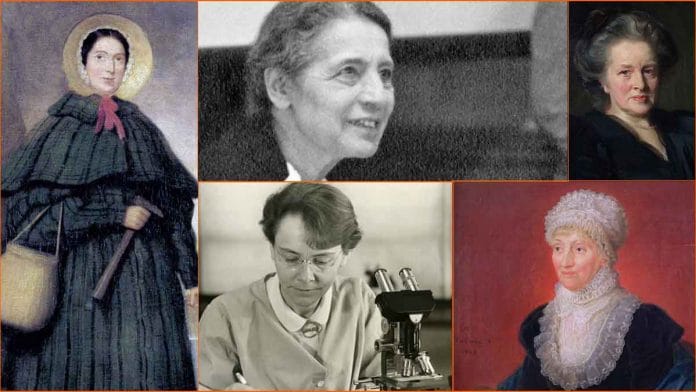

As the world observes the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, instituted by the United Nations in 2015 to address gender imbalance in these fields, on 11 February, ThePrint looks back at five trailblazers history took long to recognise.

Caroline Herschel (German astronomer, 1750-1848)

The lesser-known Herschel sibling, Caroline was the sister of astronomer William Herschel, who discovered Uranus and infrared radiation.

Caroline started off in astronomy by helping her brother catalogue objects in the sky. The siblings improved lenses to observe the night sky and went on to discover over 2,500 objects.

She was an astronomer in her own right who notched several firsts: She was the first woman to discover a comet (she went on to discover several), to win a gold medal from the Royal Astronomical Society (1838), and the very first woman to be paid for scientific work. She has an asteroid named after her, as well as a crater on the moon and a space telescope.

She was infected by typhus at the age of 10, which permanently stunted her growth. At her tallest, Caroline stood at just over four feet.

Caroline wasn’t very happy with the initial trajectory her life. She trained as a singer when her brother was a conductor, but as he drifted towards astronomy, she was forced to, too.

She noted in her memoir how she was like a “well-trained puppy” for her brother, doing his bidding, and caring for him as he focussed on building a legacy in astronomy.

Eventually, she developed a keen interest in the science herself and enjoyed her work immensely.

Lise Meitner (Austrian-Swedish physicist, 1878-1968)

Lise Meitner was well-known in European scientific circles for several reasons: She was the first female physics professor in Germany, a leading authority on nuclear physics, and Jewish. When Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in the 1930s, she was forced to flee the country and settle in Sweden.

She is most noted for her discovery of nuclear fission and co-published her results with two male colleagues in early 1939.

The three physicists were at the time probably the only ones in the world who understood that nuclear fission — where atomic nuclei split into two parts — releases tremendous amounts of energy.

This principle was the basis on which nuclear weapons were built during World War II.

However, Meitner was not awarded the Nobel Prize for her part in the discovery, with her colleague Otto Frisch winning it in 1944.

The Nobel committee reveals nominations after 50 years of an award, and Meitner’s rejection process revealed that one of the factors might have been the undermining of Jewish researchers’ scientific record in Germany.

Several posthumous honours have been conferred on her, including naming the element Meitrnerium after her.

She was the first student of physicist Max Planck, who had until then rejected women students, as was the norm. But after becoming only the second woman to get a Physics PhD from the University of Vienna, she went on to work in radiochemistry.

Just after World War I, where she served as a nurse working with X-ray machines, she struggled with a massive internal conflict centred on pursuing Physics when surrounded by death.

She also almost discovered the neutron, but instead, handed over her work and helped English physicist James Chadwick do so by corresponding with him. Chadwick eventually won the Nobel for this discovery.

Also read: Men are first authors in 3 times as many academic papers published in India as women

Mary Anning (British palaeontologist, 1799-1847)

Mary Anning is most famous for her discoveries of fossils that revolutionised how we now understand prehistoric life and biological evolution on Earth.

Born into poverty, as a child, Anning helped her father collect fossils along the beach, and polish and sell them.

She is widely believed to have been the inspiration for the famous tongue twister, “She sells seashells on the seashore”, inspired by a song by Terry Sullivan.

After her father passed away, Anning continued selling fossils and shells. After a chance discovery of the skull of an animal initially thought to be a crocodile, Anning dug around and discovered all the remaining bones.

Her collection of bones created the first complete fossil of any prehistoric animal, in 1811. It was an ichthyosaurus that lived 200 million years ago.

For the rest of her life, Anning hunted the beaches of Lyme Regis in England, now famous for the innumerable dinosaur fossils it holds. She also discovered a full structure of the long-necked marine creature, the plesiosaur, and the flying non-dinosaur, the pterodactyl.

Her work wasn’t easy. Her seaside home was flooded on several occasions by the same waves that revealed fossils to her, and she and her dog nearly died as a result once.

Anning was born into a religious family of 10 siblings who believed that life originated according to the Bible’s creationism.

When she was a toddler, she was struck by a lightning flash that killed two others. Her survival was hailed as miraculous.

However, Anning’s unusual discoveries are said to have helped the budding field of paleontology look beyond religious books and into the history of the Earth.

Barbara McClintock (American geneticist, 1902-1992)

Maize seems like an unusual thing to dedicate one’s life to, but that is exactly what McClintock did.

Much before CRISPR came along, McClintock studied cytogenetics, researching how chromosomes were related to behaviour. In the 1930s, she developing a staining technique by which individual chromosomes could be identified and studied.

She discovered jumping genes, sequences of DNA that move between the genome, but her findings were dismissed as junk science and not recognised until 50 years later.

McClintock was born to a homoeopathic physician. She was initially named Eleanor, but her parents, who found the name “too feminine”, changed it.

She is said to have developed an affinity for science at an early age, but her mother prevented her initial efforts to pursue the field over fears she would become too educated for prospective suitors.

But McClintock eventually enrolled at Cornell University, where she studied botany and earned a PhD.

Her first major recognition came in 1944, when she became only the third woman to be elected to the US National Academy of Sciences. In 1945, she became the first woman president of the Genetics Society of America. Her work earned her the third Nobel awarded to a woman in the field of physiology or medicine.

She pioneered the use of Neurospora crassa, which is now considered a model species for genetic studies.

McClintock would frequently talk about how difficult it had been for male geneticists to take her seriously, an experience that stalked her through most of her life.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (British doctor, 1836-1917)

Known as the first female physician in all of England, Anderson scored a lot of other firsts in her home country. She was the first woman dean of a medical school, first woman mayor and magistrate, first woman surgeon, and the co-founder of the first all-women hospital.

She was influenced strongly by her American namesake, Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman doctor in the US.

Born into a family of ironworkers, she was taught by a governess. Her career began as a nurse, after which she was allowed to attend to patients and operations. Her experience allowed her to obtain a private certificate in anatomy.

When she found out that colleges in Paris accepted women students, she self-learned French and applied.

Anderson, who also spoke Italian and German, was an avowed suffragist who helped circulate citizen petitions to allow women heads of families to vote. As a mayor, she gave speeches in favour of voting rights for women.

While she was never awarded or even considered for the Nobel, her legacy is epitomised by several buildings named in her honour — over 20 hospitals and medical institutions in England are named after her and her writings are preserved in the national archives at the London School of Economics.

Her daughter Louisa Garrett Anderson also went on to become a groundbreaking feminist.

Also read: More girls than boys in India want to become psychologists or journalists: Cambridge survey