Bengaluru: A new study published in the journal, Nature Climate Change, has attempted to examine the effects of extreme cold waves in the oceans, which have not been very well researched before. Researchers from Australia, France, the UK and South Africa analysed the deaths of 260 marine organisms belonging to over 80 species affected in a single event off the South African coast in 2021, which, they discovered, was an extremely intense cold wave in the waters.

The authors also studied the sea surface temperature data of the last 41 years in the region, and included 33 years of wind records in their analysis, to figure out the intensity and frequency of such cold ‘killer events’ in this region. Their data showed that these cold waves resulted in species migration.

They used the data from tagged bull sharks over the last 40 years, and showed that these sharks change their behaviour and habitat as a result of cold upwellings in the ocean. The sharks avoided waters with temperatures lesser than 19°C, and also started swimming closer to the surface to avoid deeper colder waters.

The researchers further discovered that these extreme cold waves increased in intensity between 1981 and 2022.

The report suggests that these cold events could result in ‘bait and switch’ situations, where a species’ range expands due to rising temperatures of water, while unexpectedly also exposing them to extreme cold events in the same regions.

This is particularly dangerous for migratory marine megafauna species like bull sharks, that are operating dangerously close to their long-term thermal limits, the study explains, increasing their vulnerability to sudden and extreme temperature changes in the ocean.

The researchers have sought more investigation into marine cold waves, an understudied aspect of climate change.

Also Read: Pacific islands leaders grant whales & dolphins ‘personhood’ status. India did it over a decade ago

Breaking down a killer cold wave

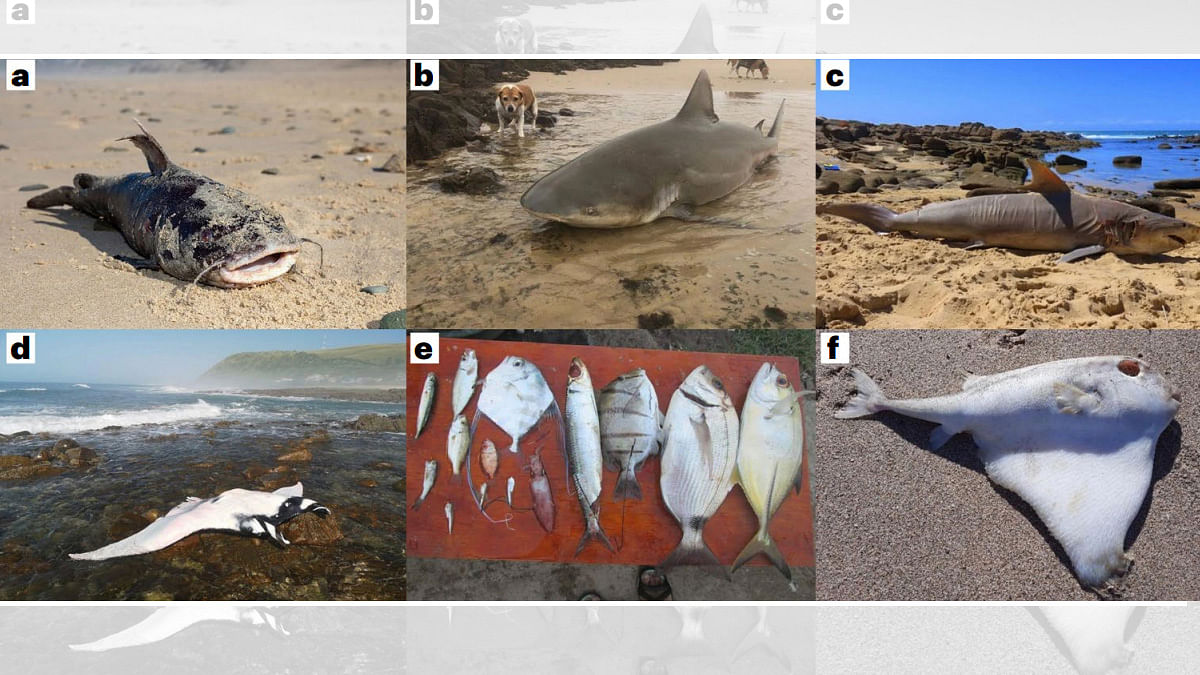

The 2021 marine cold wave, which occurred within a system called the Agulhas Current, culminated in the carcasses of at least 260 organisms getting washed up along the coastline of South Africa on 2 Marchthat year.

The dead animals included not just megafauna like various sharks, but also deep sea organisms like those belonging to the octopus family (cephalopods), manta rays, and more. Nearly three quarters of the animals were at the closest boundary to the poles in their habitat.

Temperature and wind data indicated that warming waters were resulting in wind currents that favoured the formation of cold upwellings in the Agulhas Current, and less mildly in the East Australian Current, both in the Indian Ocean.

Bull sharks tend to live in tropical and sub-tropical waters where the temperatures are warmer. Long-term monitoring data indicates that they move poleward. Data from observing 4,702 individuals showed that temperatures below 19°C are too cold for bull sharks.

Data collected off the coast of Australia also match the same findings. In cold wave events on both coasts, sharks were observed to swim closer to the surface when migrating through cold waters.

The research suggests that if cold upwellings become more frequent and intense, sub-tropical and tropical marine megafauna will be pushed to the edge of their thermal limits. The authors surmise that such cold upwellings can lead to contracts in megafauna habitat among mobile marine animals resulting in large-scale ecosystem changes in the oceans.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: India’s first semi-cryogenic rocket launch deferred 3rd time in 2 weeks. Here’s why