New Delhi: Warmer European winters, colder North America, and “searing” heatwaves in Australia. Four consecutive years of record-setting heat, and record rise in sea level. CO2 levels higher than ever seen before.

The 25th annual UN World Meteorological Organisation report, released last week, was just the latest analysis to set forth a dim outlook for Earth as it grapples with climate change.

According to the report, all the indicators point to the same conclusion: Climate change is accelerating and its consequences are affecting people on every continent. Apart from the aforementioned factors, it also points to the fact that both Arctic and Antarctic sea-ice extent is below average, and that glaciers are receding.

Glacier records covering 19 mountain regions, the report states, indicate that 2017-18 was the 31st consecutive year of negative mass balance, which means that glaciers lost more mass by melting/calving than they gained by snow/rain.

“This report is another in the long, long list of reports by authoritative bodies on climate change,” Will Steffen, a prominent scientist with the Climate Institute at the Australian National University, said in an email to The Print.

“The message is consistent and clear from all of these reports — climate change is occurring at an increasing rate, it is already having severe impacts on many parts of the world, and the risks of very serious damage in the future are increasing,” Steffen added.

Also read: Study shows climate change has a new victim — a type of cloud

A vicious cycle

Perhaps the most important factor in accelerating climate change is the total greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere. Despite the promises and efforts made by some cities, countries, and businesses, following the Paris agreement in 2015, global carbon dioxide emissions continue to rise.

However, there are other factors at play.

There is increasing scientific evidence of several self-reinforcing feedback loops (aka positive feedback loops) in the climate system that are also believed to be responsible for the accelerating pace.

“For example, rising temperatures make boreal forest (the large band of forests across the north — Canada, US, Russia) more susceptible to insect attacks and fires, which release carbon dioxide to the atmosphere,” said Steffen. “This warms the climate even more, which increases the probability of insect attacks and fires, and so on.”

According to scientists, we are seeing many more of such cause-effect-cause cycles that are making climate change worse, fast.

The disappearing Arctic sea ice is considered by many scientists to be the culprit for the sky-rocketing temperatures in the Arctic.

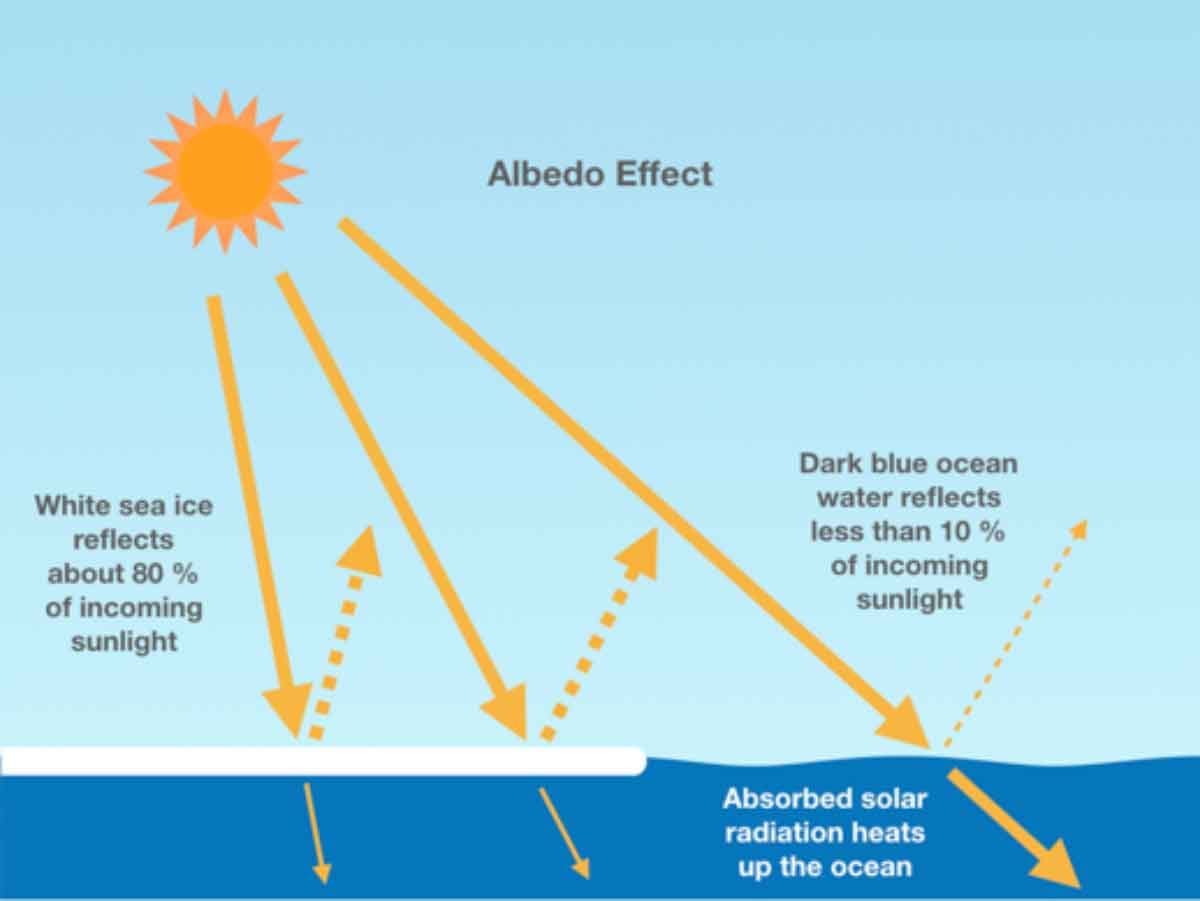

“Global warming causes ice and snow to melt, which exposes the dark ocean or land underneath. Dark surfaces absorb more of the sun’s energy rather than reflect it back to space, so more warming occurs,” wrote Jennifer Francis, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Research Center, US, in an email to The Print.

“That warming melts more snow and ice, which exposes more dark soil and ocean [and so on],” she added.

Some studies suggest that the sea ice and land snow feedback loop alone might be amplifying global temperature rise by 25 per cent or more.

In other words, it is accelerating global warming as if we were emitting an additional 25 per cent or more of the greenhouse gases we are currently ejecting by burning fossil fuels.

Also read: How global media goes wrong on coverage of climate change

Permafrost

A recent UN report concluded that it is now inevitable that winter temperatures in the Arctic will increase by 3°C to 5°C over 1986-2005 levels by 2050.

It also warns of another, potentially catastrophic, feedback loop — thawing of permafrost.

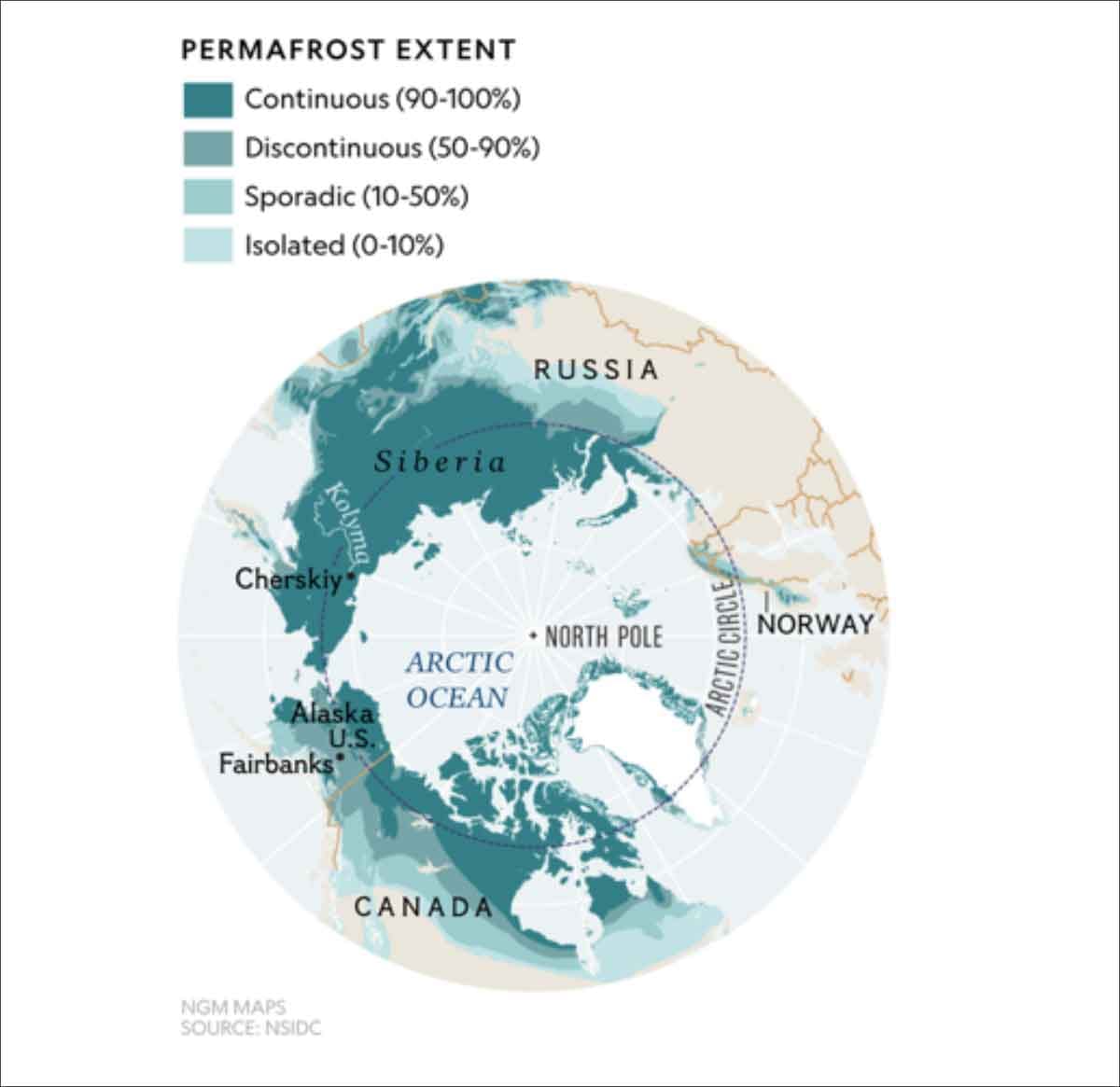

Permafrost is land that has been frozen for two or more consecutive years. About a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere is covered in permafrost.

The top layer of permafrost soil is rich in plant and animal remains. Due to rising temperatures, the permafrost is starting to thaw.

As it thaws, microbes in the soil decompose the organic matter and release carbon dioxide and methane, both very potent greenhouse gases, which contribute further to rising temperatures and, in turn, to more permafrost thawing.

It is estimated that the entire world’s permafrost holds 1,700 billion tonnes of carbon, which is twice the amount currently present in the atmosphere. Permafrost also contains frozen viruses of deadly, unfamiliar diseases that could threaten life across the globe if released. This is one Pandora’s box we do not want to open.

These feedback loops, along with several others, have global implications. Warming over the Arctic, for example, is accelerating the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, thus increasing its contribution to sea-level rise.

Greenland is the largest island on our planet with a total area of about 2.16 million sq km.

More than 80 per cent of its surface is completely covered in ice that is more than a couple of kilometres thick in some parts, forming the second-largest ice sheet in the world after Antarctica. And it is melting. Since 2012, Greenland has become the largest single contributor to sea-level rise, adding about 13 millimetres every year.

Currently, Greenland holds enough ice to raise global sea level by 7 metres or 23 feet. Although it is unlikely that all of it will melt anytime soon, if the Arctic feedback loops continue unchecked, it could have serious repercussions for low-lying islands and coastal cities.

Some of the world’s most populated cities like Mumbai in India, Dhaka in Bangladesh, New York in the US, and Venice in Italy, are only a few feet above sea level on average and highly vulnerable to sea-level rise.

Also read: The many ways climate change will leave us high & dry, in one table

‘What happens in the Arctic’

It is a common saying in the climate science community, ‘What happens in the Arctic, does not stay in the Arctic’.

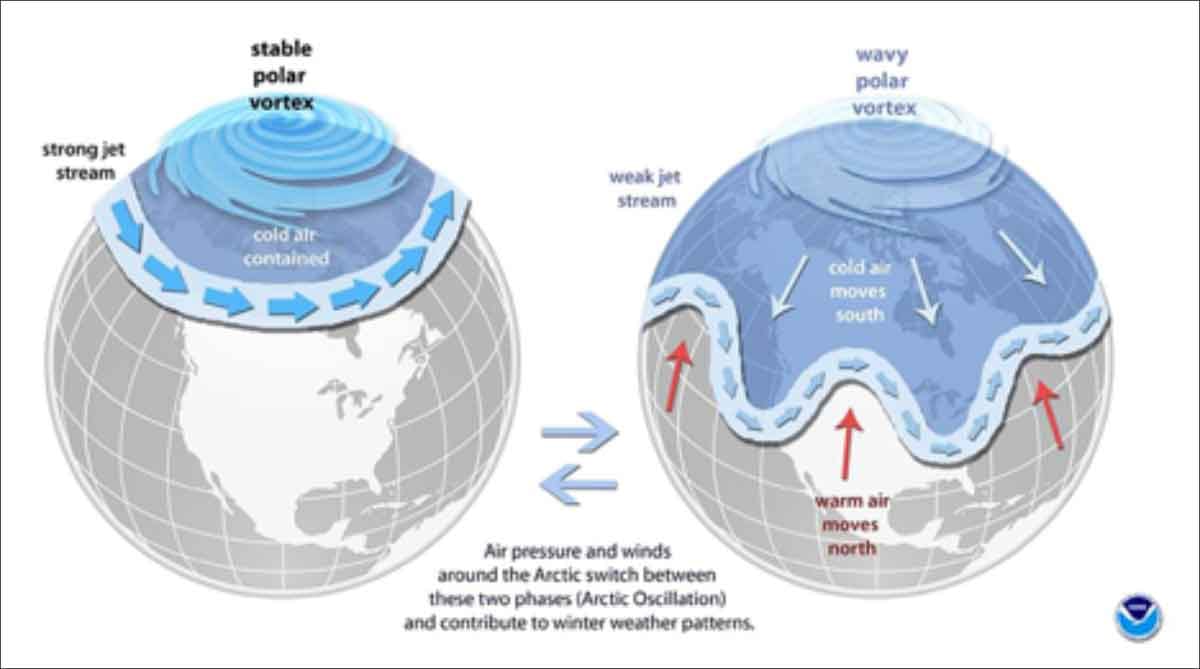

Some recent studies show a strong link between warming in the Arctic and extreme weather around the world, due to the disruption of the polar jet stream.

The polar jet stream can be thought of as a river of fast-flowing air circling the northern hemisphere high above the ground.

“The difference in temperature between the Arctic and areas farther south is the main ‘fuel’ that drives the jet stream, so if the Arctic warms faster [due to the positive feedbacks], the temperature difference decreases, and that fuel is diminished,” said Francis.

This should concern all of us because the jet stream creates almost all of the weather we experience.

“If the [jet stream] moves slowly, our weather conditions become more persistent. If that goes on long enough, it can result in droughts, prolonged heat waves, flooding, and long cold spells… the multi-year drought in the western US states is one example [of disrupted jet stream behaviour],” Francis added.

Our climate is an interconnected web of many processes that affect one another. It is imperative that when we talk about climate change, we discuss the possibility of complex exponential changes rather than a simple linear response to our activities.

It follows that if countries around the world do not get their acts together, climate change may soon get out of our control and drive itself. According to the UN, we must reduce our carbon emissions by 45 per cent by 2030, and to net zero by 2050, in order to avoid runaway climate change. This is a daunting task with nothing less than our future generations’ survival at stake.