Chang’e-4 landed on the far side of the moon Thursday, setting the stage for a new chapter in India and China space race.

Bengaluru: China made history Thursday by becoming the first country to land a spacecraft on the far side of the moon, a feat India is expected to repeat soon with Chandrayaan-2.

Not a lot of information is available on Chandrayaan-2 just yet, but the overall mission is similar in objectives and area of operation to the Chinese craft, Chang’e-4. Its launch date is yet to be announced, but its landing site is expected to be close to that of Chang’e-4.

Mission profile and objectives

Chandrayaan-2, India’s second mission to the moon, will comprise an orbiter, a lander named Vikram [after the father of Indian space programme Vikram Sarabhai], and a rover.

It was supposed to be launched Thursday, but the mission was postponed.

The landing site for the Chandrayaan-2 rover is expected to be between the two craters Manzinus C and Simpelius N near the southern pole of the moon.

The orbiter will go around the moon at an altitude of 100 km, acting as a communication relay between the lander/rover and Earth.

The far side of the moon can never be in direct line-of-sight with Earth, proving direct radio communication impossible, which is why the orbiter is needed.

It will carry five instruments: A radar that will probe a few metres below the surface to detect water ice, two spectrometers to study the minerals on the surface, one that studies the lunar exosphere and a camera for geology.

The Vikram lander will perform a soft landing on the lunar surface. It consists of four payloads that will study moonquakes, heat properties of the lunar regolith (soil), the lunar surface charging due to radiation, and measure of electrons in the atmosphere when radio waves pass through it.

The six-wheeled rover will be deployed by the Vikram lander soon after landing, and will operate on solar power. It will have two cameras in the front that function as the rover’s eyes: Their combined imaging will provide a 3D visualisation of the path ahead, enabling scientists to plan its next move.

Four of its grooved wheels have independent steering, which will enable them to get unstuck from the lunar regolith. A total of 10 electric motors will help the rover navigate.

The mass of the orbiter, lander and rover respectively is expected to be 2,379 kg, 1,471 kg, and 27 kg. The mission is expected to last a year, with the lander and rover both working for about a fortnight.

The Chandrayaan mission is completely indigenous, with all parts and payloads developed by India.

Also read: China’s Chang’e-4 first spacecraft to land on dark side of the moon

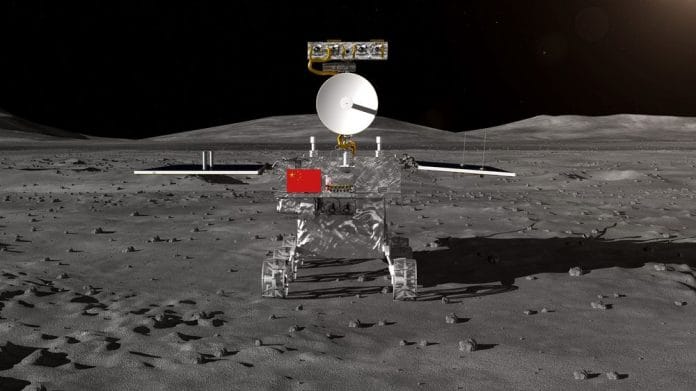

China’s eyes on the moon

China’s Chang’e-4 is one of the country’s six missions for lunar exploration, all of which work in pairs.

Chang’e-1 and 2 were orbiters (2007 and 2010), Chang’e-3 & 4, landers (2013 and 2019), while the fifth and sixth missions will be aimed at bringing back samples in the 2030s, with China also planning to build a lunar outpost on the south pole of Earth’s satellite.

The Chang’e-4 landing site is the Von Kármán crater in the South Pole-Aitken basin, a large impact structure believed to have formed when a big body collided with the moon. It covers nearly a quarter of the moon’s surface.

The collision is expected to have exposed the lunar mantle, the region just below the moon’s crust but above the core.

By exploring this region directly, we expect the rover to learn more about the early solar system, lunar activity, how the moon was formed, and by extension, more about how Earth was formed as well.

While Chandrayaan-2 will have an orbiter going around the moon, Chang’e will use a relay satellite in a halo orbit (orbiting an empty point in space) at the L2 Lagrange Point (points in a two-body system where the gravitational pull of the two bodies, such as Earth and the moon here, cancels out, enabling a stable orbit to ‘park’ spacecraft).

This satellite, called Queqiao, was launched earlier last year.

The lander carries with it a biosphere experiment consisting of tomato, potato and a flowering plant’s seeds, and silkworm eggs, within a sealed container.

The biosphere will function by itself, where if the eggs hatch, the carbon dioxide will feed the plants, and their photosynthesis will feed the larvae. A miniature camera will send progress images of the experiment. It carries two more cameras to map the terrain and a spectrometer to study the solar wind.

The 140-kg rover, named Yutu-2, is also solar-powered and operated by six wheels. It contains four payloads: A camera as ‘eyes’, a ground-penetrating radar similar to Chandrayaan’s, a spectrometer to identify minerals and trace gases, and an analyser to study the formation of lunar water and the interaction of the solar wind and the lunar soil.

The rover and the lander together weigh 1,200 kg. Chang’e-4 carries international payloads developed by Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Saudi Arabia. The mission is expected to last a year, but Chinese scientists are confident it will go on longer.

Indo-China space race

Both India and China are competing to race ahead in space exploration, with India targeting a second moon mission, a Venus mission, and a second Mars mission in the coming years.

China too has the same missions lined up.

As ISRO continues to announce a stream of missions, China set a world record with 38 launches in 2018.

India developed its own indigenous GPS, just as China did theirs.

The Chinese have also seen tremendous involvement of private players, raising the value of their space industry, and India is yet to play catch-up.

The Chinese space budget is estimated to be nearly Rs 56,000 crore a year, second only to the US. By contrast, India’s budget is less than Rs 10,000 crore.

Even so, 2019 looks all set to prove another exciting year for the space race brewing in Asia.

Also read: Chandrayaan-2 to be launched in Jan 2019: ISRO chief

India has the zero sum mentality to everything. Even China’s space program is perceived as a race, which India is in no position to compete but wasting its little valuable resources instead of developing its ailing economy and broken infrastructure for Indians welfare.

It will not land on far side of the moon. please correct this wrong info.

The main objectives of the Chandrayaan-2 mission are to show the ability to soft-landing on the lunar surface and then run a robotic rover on the surface. India has successfully launched the Chandrayaan-2 mission on July 22, 2019, and is now on its way to the moon and it’s going to be a soft landing. The main scientific goals include the studies of lunar topography, mineralogy, elemental abundance, the lunar exosphere and the signatures of hydroxyl and water ice.

China sent 1st Chinese to space in 2003 in their manned mission, we will send Indian through Indian mission to space in 2022, where is the race, I don’t get it. Be realistic.

Both India and China have made humanity proud. Great to see the great passion of both in exploring the fascinating science and technology.

Again, when has China said it was in a space race with India or the USA as the article’s author implies???

As far as I can read, the Chinese take on space exploration is more “slow and steady” and “lets learn our stuff” rather than “we got to beat the Indians” or “bury the Americans”. Correct me if I’m wrong.

It’s interesting. But should India’s space policy be seen as a competition with China? It would be a mistake to renew at the Asian level the space competition of the early 1950s between the US and the USSR. We quickly saw the consequences of such a competition. One must be realistic and be at the level of the means of India, and not contribute another area of rivalry between India and China, which does not exist. Except maybe in the mind of the article’s editor !!!