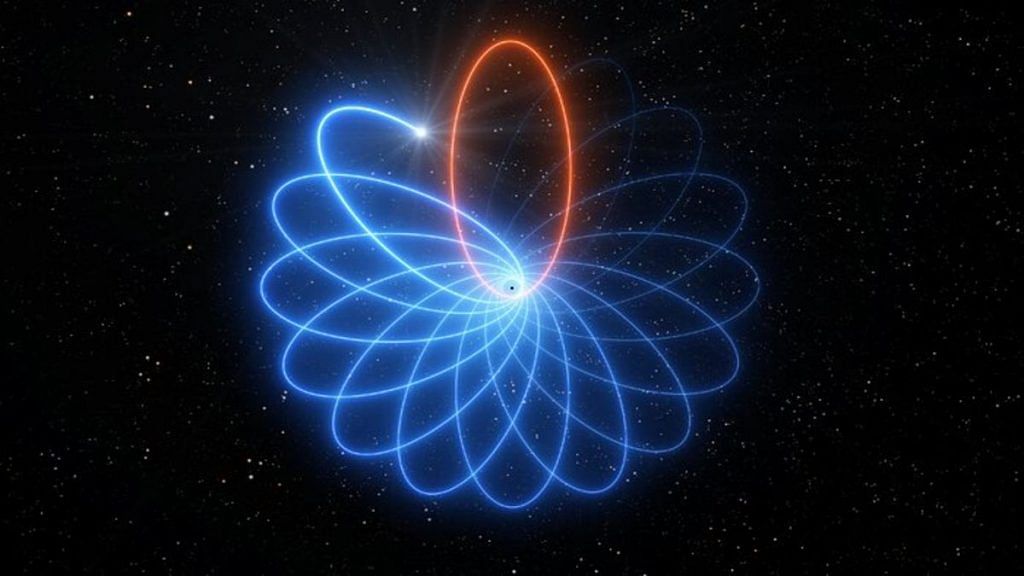

Bengaluru: S2, a huge star in the Milky Way, is locked in a dance around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the galaxy, astronomers have found. Its orbit around the black hole is not an ellipse like the Earth’s around the sun, but rather a rosette, a flowery pattern, that sits exactly in line with predictions made by physicist Albert Einstein in his Theory of General Relativity.

The findings were backed by 27 years of high-precision observation of S2 by the Very Large Telescope of the European Southern Observatory — a 16-nation intergovernmental science and technology organisation — and published Thursday in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. The telescope is located in the Atacama Desert in Chile.

The orbit of S2, the researchers said, does not stay in place and undergoes a change because of a “wobble”, called precession, which occurs as the star goes close to a black hole, triggering relativistic effects as predicted by Einstein in his theory.

Relativity states that a body as massive as a supermassive black hole would “bend” or warp the geometry or fabric of space-time, and the findings directly confirm this.

“Einstein’s general relativity predicts that bound orbits of one object around another are not closed, as in Newtonian Gravity, but precess forwards in the plane of motion,” said Reinhard Genzel, director at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) in Garching, Germany, and the project lead, in a press release.

“This famous effect — first seen in the orbit of the planet Mercury around the sun — was the first evidence in favour of general relativity. One hundred years later we have now detected the same effect in the motion of a star orbiting the compact radio source Sagittarius A* at the centre of the Milky Way,” he added.

“This observational breakthrough strengthens the evidence that Sagittarius A* must be a supermassive black hole of 4 million times the mass of the sun.”

Also Read: Earth has a second moon — car-sized, dark and temporary

Supermassive black hole at centre of Milky Way

Supermassive black holes (SMBH) are the most dense black holes found in the universe, and the one in the centre of our galaxy is said to have at least as much mass as 40 lakh suns. The black hole is about 26,000 light years from the sun, and is called Sagittarius A* or Sgr A* (pronounced Sagittarius A star).

S2 orbits Sgr A* at an average distance of 20 billion (2,000 crore) kilometres, about 120 times the distance between the sun and earth, taking 16 years to complete one revolution. This makes it one of the closest stars ever known in orbit around the black hole.

At its closest approach, the star zips around Sgr A* at almost three per cent of the speed of light.

As it approaches its closest point to Sgr A*, called the pericenter, it precesses or wobbles in orbit by coming closer to the black hole each time because of the warping of space-time.

This kind of precession is called ‘Schwarzschild precession’, named after German astronomer Karl Schwarzschild, who calculated mathematical solutions to Einstein’s field equations of general relativity.

As S2 swings around Sgr A*, it shifts by approximately one-fifth of a degree or 12 arc minutes, thus drawing a tighter curve and continuing on a slightly shifted egg-shaped orbit, like a spirograph design.

The astronomers were able to determine that such a tightening of the orbit is not due to the presence of any other unknown object or groups of stars, but directly from the effects of Sgr A*.

In the solar system, Mercury, the planet closest to the sun, has been known to follow a similar orbit — a fact known since before the times of Einstein even though astronomers of yore were unable to explain this orbit. When Einstein applied his calculations to the orbit in 1915, they fit so perfectly he reportedly had heart palpitations. Mercury’s orbit changes by 43 seconds of arc per century.

The S2 findings mark another step in understanding the science of Sgr A* and other black holes, like being able to determine the spin of the black hole. More powerful telescopes, such as ESO’s upcoming Extremely Large Telescope, could help see much fainter stars that could be orbiting much closer than S2 and could experience more relativistic effects from the supermassive black hole.

Also Read: First highest-resolution images of Sun are here, reveal never-seen-before features