The Supreme Court-appointed committee’s exit report lays bare a year of bitter turf war with the government regulator.

As the controversial, year-long tenure of the Supreme Court-appointed Lodha committee ended last week, not only does the mandate to reform medical education remain unfulfilled, but its own exit report lays bare a bitter turf war with the government regulator.

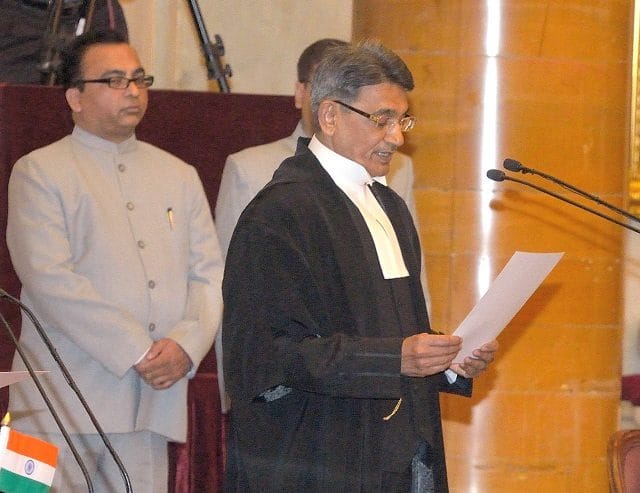

The committee, headed by former chief justice R.M. Lodha, was appointed on May 2, 2016 to bring in transparency and accountability within the Medical Council of India (MCI) and oversee its statutory functioning.

But the policy recommendations in the final report that the three-member panel submitted to the top court, and accessed by ThePrint, are identical to the mandate set a year ago.

The panel, also comprising former comptroller and auditor general Vinod Rai and director of the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences Dr S.K. Sarin, was dissolved last week. The government has now appointed a fresh team of five eminent doctors to oversee the medical regulatory body.

The mandate and recommendations — regarding bringing in a standardised central counselling scheme for admissions, improving accountability and transparency of the MCI and rationalising the assessment procedures for colleges — read almost the same, with a bit of rearranging of words.

By its own admission, the biggest reform the committee recommended was to make it mandatory for medical students to clear an exit test. It says the members gave the “highest priority” to establish a licentiate exam.

The report says it was “the single most important step to ensure high standards of medical education and health care in India” to introduce the National Exit Test (NEXT) for MBBS graduates to qualify themselves as doctors and to secure registration for clinical practice.

But this has not found many takers. Only 12 states and 4 union territories have favoured the idea, the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare said in April.

Another achievement the report mentions is that the committee directed the MCI to follow the “Assessor’s guide-2017” that it had prepared for granting approvals to private medical colleges. The guide lists responsibilities of the regulators, colleges and the ministry. Not only did the MCI fail to implement it, but the committee itself diluted many of the guidelines when it granted approvals to dodgy, under-equipped colleges.

Last month, the MCI debarred 34 colleges which were granted approvals by the committee because they did not meet required standards – exposing the year-long running feud between the two.

The committee report hints at the turf war. It states that the oversight panel’s performance was “amidst all efforts of MCI to defy remedial directives of the oversight committee and frustrate the implementation of the court’s ruling”.

Other key policies that the oversight committee recommended, including the removal of an upper age limit for post-graduate medical courses, increasing the student-professor ratio to 3:1 and designating faculty members in a time-bound manner are yet to see the light of day. But even these were not followed by the MCI because it says it required a lot more groundwork to implement these recommendations.

“The committee has not fulfilled the mandate of reforming the MCI,” a medical college administrator, who did not wish to be identified, said. “Substantial issues like capping fee, fixing a minimum budget to run a medical college and creating a national registry of doctors have been left out.”

Many say the casualty in this contested judicially-mandated exercise is the urgently needed reform in the country’s medical education.

In its report, the Lodha panel has asked the court to direct the MCI to implement its orders with immediate effect. But now the court has passed the buck on to the new committee, making it clear that the regulator is far from being reformed.