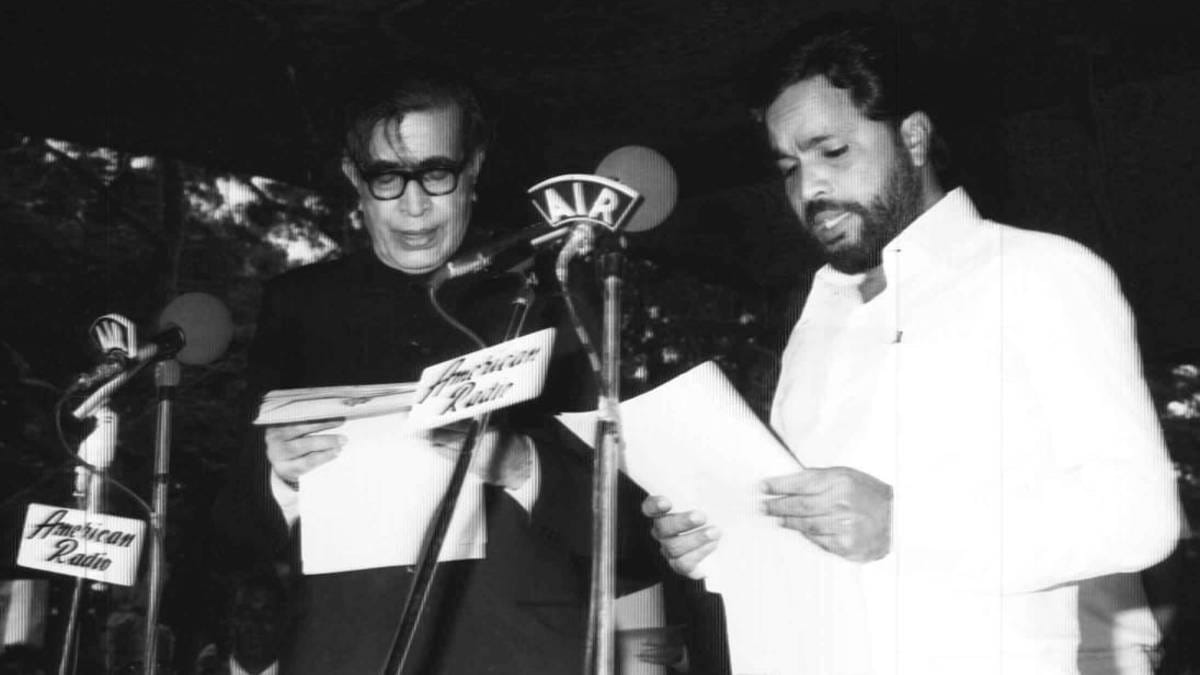

Bengaluru: Siddaramaiah, 77 years old, Wednesday became Karnataka’s longest-serving chief minister, surpassing the record held by D. Devaraj Urs.

He has completed 2,792 days as CM, against Urs’ 2,790 days over two terms (1972-77 and 1978-80)—a significant milestone given the historical volatility of Karnataka’s political landscape.

Urs’ tenure was broken by President’s Rule but he returned to power two months later.

“I never did politics to break someone’s record; I just got the opportunity. I do not even know how many years or days Devaraj Urs served (as CM),” Siddaramaiah told reporters in his home district of Mysuru Tuesday.

Despite ongoing speculation of a change in leadership, Siddaramaiah remains confident—and even defiant—of completing a second full term in office. “It all depends on the (Congress) high command’s decision,” he told reporters.

Should he achieve this, it would be another historic milestone in a state where fractured verdicts, volatile politics and frequent regime changes are the norm. He is only the third CM so far to have completed a full-term in office, the others being Urs and S. Nijalingappa.

Siddaramaiah’s rise has been meteoric and shows immense political astuteness, analysts and political observers say.

“The importance of Siddaramaiah in our times is that he is the only CM who speaks the language of social justice. Because no other national or state-level leader is making certain bold statements that Siddaramaiah has been making, although one may have a problem with the language or the imagination of social justice,” A. Narayana, faculty member at Azim Premji University and political analyst, told ThePrint.

Siddaramaiah’s image as a champion of the backward classes, his constant attacks at the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), mobilising of support against Hindi imposition, demand for higher share in central taxes and relentless attacks on Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Union Home Minister Amit Shah and the BJP are also what makes it that much harder for the Congress and Rahul Gandhi to replace him, according to the analysts.

Also Read: How redoing Karnataka ‘caste census’ weakens CM Siddaramaiah without strengthening Shivakumar

‘What does a shepherd know about finance?’

Siddaramaiah was born in August 1948 at Siddaramanahundi, a nondescript village in the district of Mysuru (or Mysore as it was called back then). He hails from the Kuruba community (traditionally shepherds), and broke social and economic barriers to first get a law degree and then won election after election since his first poll outing in 1978 when he became a taluk board member in Mysuru.

In his initial years as an advocate, Siddaramaiah was deeply influenced by socialist thinker Dr Ram Manohar Lohia and later came under the tutelage of professor M.D. Nanjundaswamy, founder of Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha, a powerful farmers’ movement started in 1980.

“When I was preparing the first budget as finance minister, there were gibes like ‘what does a shepherd know about finance?’ But I did not pay heed to such insults,” Siddaramaiah recalled.

The Kurubas, one of the more backward communities in Karnataka, have over the years become a force to reckon with in the state’s deeply caste-centric politics and society.

Siddaramaiah’s political trajectory was shaped by the discrimination he faced in his early years, which he converted into his biggest strength.

Like Urs, Siddaramaiah too got backing from the AHINDA (Kannada acronym for minorities, backward classes and Dalits) although he now keeps his legacy distinct from that of Urs.

“(There is) no comparison between me and Devaraj Urs,” Siddaramaiah has said, stating that both leaders worked at different points in time.

Urs and Siddaramaiah are both from Mysuru, and the CM seems to suggest that the similarities end there.

But analysts point to many similarities and differences between the two leaders.

‘Not party but coalition builder’

Siddaramaiah unsuccessfully contested the Mysuru Lok Sabha polls in 1980 but entered the state legislative assembly three years later when he defeated D. Jayadevaraja Urs of Indira Congress in Chamundeshwari, standing as an independent. During his political career spanning over four decades, he has contested 13 elections and won eight of them.

He started his innings as an MLA by extending support to the coalition headed by then CM Ramakrishna Hegde and becoming the chairman of Kannada Kavalu Samithi (Kannada Watchdog Committee), giving an insight into the tactful politician he would go on to become.

“To be successful in Karnataka politics, one has to be a coalition builder. And Siddaramaiah has done that with great success,” said one Bengaluru-based analyst, requesting anonymity.

Siddaramaiah proceeded to serve as the minister of animal husbandry, sericulture, transport, education and other departments. In 1994, he became finance minister under H. D. Deve Gowda and has since presented a record 16 budgets, wielding influence over the treasury to this day.

Analysts compared Siddaramaiah with Urs and the two leaders’ perception of politics.

Urs had revolted against then Congress leader Indira Gandhi and led a breakaway faction, while Siddaramaiah revolted against his mentor, Deve Gowda of the Janata Dal (Secular).

They say that Urs conducted his politics as a “statesman” but Siddaramaiah is more of a politician and administrator.

Though many leaders, including Veerappa Moily, S. Bangarappa and several others were under the direct tutelage of Urs, Siddaramaiah entered the assembly a year after his death.

“Urs was a party builder and created the opportunities for himself. In Siddaramaiah’s case, he is not a party builder and his politics was limited to occupying places that were vacant and being at the right place at the right time,” Narayana told ThePrint.

After being denied the CM’s position within the Janata Party and later Janata Dal (Secular), Siddaramaiah was expelled from the party by Deve Gowda in 2005.

He then joined the Congress in 2006 and was made Leader of the Opposition in Karnataka post the 2008 assembly polls, and then the CM in 2013, with the Congress overlooking several seniors, including Mallikarjuna Kharge, for the post.

Urs had won his first term as party president and then led the Congress to elections again as chief minister. In contrast, as sitting CM, Siddaramaiah lost in Chamundeshwari in 2018 and scraped through in his second seat of Badami.

Even in 2023, Siddaramaiah was asked to contest the assembly polls from his home seat of Varuna as the Congress was apparently not sure about him winning from a new constituency.

Urs & Siddaramaiah’s policies

Siddaramaiah, according to those who know him, is concerned about the legacy he leaves behind, while Urs is already considered an icon of social justice in Karnataka.

The former CM ushered in land reforms in 1974 and his Ulidhavanige Bhoomi (tillers are the owners of land) policy marked a significant change in the state’s social, economic and political landscape. Though this would lead to several land-owning communities distancing themselves from the Congress, it would give the party a whole new constituency of support, including the poor, landless and oppressed classes.

“Essentially, he (Urs) didn’t allow them (people who lost land) to go to court and created land tribunals and then he ensured that the majority in each village got land. He created a political base of it,” said the Bengaluru-based analyst.

Siddaramaiah would follow suit, ushering in a wave of welfare-based politics, including the “Bhagya” schemes in his first term as CM and welfare guarantees in the second.

Urs also pioneered the backward-class reservation policy in Karnataka, constituting the state’s first backward classes commission. Siddaramaiah has also tried to empower the OBCs (Other Backward Classes) by action, but has fallen short of any actionable consequence.

Analysts pointed out that Urs operated during the Emergency, which gave him more powers to implement revolutionary reforms and usher in changes that were seen as essential at the time.

Under Siddaramaiah, Karnataka was the first state to undertake a comprehensive socio-economic survey in 2015. However, he is criticised for not implementing its report as remaining in power was seen as prioritised over social justice.

According to Narayana, Siddaramaiah’s clamour for social justice is not backed by “vision”. But he acceded that both Urs and Siddaramaiah operated under different circumstances and different high commands.

“In terms of individual actions, you cannot expect Siddaramaiah to replicate Urs because they had to operate at different times. In terms of substance, what Urs did had vision and Siddaramaiah’s measures lack that. He (Siddaramaiah) did certain things which are unique but not necessarily revolutionary,” he explained.

Siddaramaiah strengthened the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan & Tribal Sub Plan, introduced reservations in government contracts, brought in scholarships and other incentives for the OBCs. But his “revolutionary reforms” were more directed towards the SC/ST communities than the OBCs. He has also been trying to get the Kuruba community into the ST fold despite stiff resistance.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Who are Panchamasali Lingayats & why they’re so important in Karnataka politics