His award of the Nobel Prize for Literature provided Rabindranath with the opportunity to speak to the world through his lectures. He was convinced that his world mission was ‘divinely willed’ and therefore he became enthused to write the lectures directly in English. The lectures were subsequently published as collections of essays with the titles Sadhana: The Realisation of Life (1913), Nationalism (1917), Personality (1917), Creative Unity (1922), Talks in China (1924, 1925) and The Religion of Man (1931). These books are important even now because they represent what Rabindranath sought to communicate to the East and the West for a change in the world’s psychology in order to embrace the new environment of the new age. That change would need a new and alternative education founded on a different freedom, a different universalism.

Rabindranath’s essays were written out of concern for the ‘Nationalist’ direction in which the Western nations were taking their own people and, in the process, also influencing the diffident East. He referred to Nationalism or Nationalist with a capital ‘N’ because Rabindranath’s objection was to territorial nationalism, in other words to the aggressive policies of the nation-state. His goals were different. His goals were for India to uphold the multiplicity of the local communities within India’s geographical boundaries, for India to combine with the unity in the diversity of Asia, and for the West to move towards ‘world change’ through an effort to reach the unity of mankind. The Santiniketan endeavour for a new education was intended for a move away from Nationalism, Patriotism, Statism, and also Capitalism. To give an example Rabindranath insisted on the best technology for Visva-Bharati’s scientific activity but without the greed of profit that Capitalism stood for. The Santiniketan experiment presented a challenge to embrace humanity with a message that Rabindranath was idealising for the future of mankind.

In the 1920s and the 1930s Santiniketan became, as if, India’s guest house for the world. Rabindranath travelled to thirty countries in five continents across East and West from 1912 to 1932 with his appeal for international cooperation. Wherever he went, he invited men and women to Santiniketan if they felt an empathy for his idea of international cooperation. He invited artists, craftsmen, musicians, scholars, economists, ethnologists, malariologists, agricultural scientists, even dislodged Jewish intellectuals like Alex Aronson, whose Santiniketan Diaries are published. Aronson first came to Santiniketan in 1937 after finishing his Bachelor’s degree in English Literature at Cambridge. He had met a young Chinese scholar at Cambridge who had been to Santiniketan and told him about the place, told him about Rabindranath’s educational experiment, a community where the Hindus and the Muslims stayed side by side in harmony. In an interview with me on a later visit to India Aronson mentioned how he wrote off to Santiniketan asking anxiously if he could come so as to get out of the oppression of Central Europe at the time. The Santiniketan administration wrote back promptly asking him to come, offered him a teaching job and a half fare from England to India for his travel. Aronson stayed for seven years in Santiniketan. Aronson told me ‘Santiniketan became a salvation for him, a shelter from Auschwitz, not just merely a physical shelter but a spiritual shelter. He added that Santiniketan was just the right place for a Central European who wanted to develop himself.’

Other examples are extant. Tan Chameli Ramachandran, who is a practising artist in Delhi today, belongs for instance to that more or less forgotten Santiniketan history. Her father, Tan Yun-Shan, was the Chinese scholar who came to Santiniketan from Malaya where Rabindranath met him during his travels in South East Asia and invited him to Santiniketan. Professor Tan came and lived in Santiniketan till the end of his life. In his interview to me Professor Tan said that he found Santiniketan to be like a big family where everyone gathered around Rabindranath in the evenings. He added Santiniketan is his spiritual home. Chameli was born in Santiniketan and named after Santiniketan’s favourite flower, chameli.

Also read: Not wearing a saree may be an issue in Carnatic music. Wearing one won’t be a bed of roses either

Europe was in turmoil, its old ideals were shattered by the First World War, and that is why there was need at this time for a spiritual understanding and cooperation between the nations. Rabindranath felt strongly that a meeting of the minds of the East and the West should take place at the Santiniketan ashram and the Santiniketan school. He wrote to his friend William Rothenstein,

The Santiniketan quest was for a cosmopolitan cultural identity without the hegemony of any one culture over another or of any one nation over another. The foundational idea was for a ‘meeting’ of minds and hearts from all possible backgrounds towards an understanding of other histories and cultures. An example was the Austrian student of art history, Stella Kramrisch, who came to Santiniketan in 1921 on Rabindranath’s invitation to teach European art history and went on to become a celebrated head of the Oriental Section of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The opportunity to take part in Santiniketan’s Visva-Bharati initiative led Kramrisch to a passionate and scholarly career in Indian Art.

Connecting with the world was one aspect of the Santiniketan ideal from its very inception. There was also its other ideal of ‘total activity’ to learn about life in all its variety. With time the rural scheme of Sriniketan was made into a regular laboratory for carrying out experiments by the visiting experts with the participation of the local villagers. Rabindranath was convinced that there was no hope for the peasants without the application of modern techniques in agriculture.

As early as in 1906 he had sent his son Rathindranath and his friend’s son Santosh Chandra Majumdar to the University of Illinois in the USA to study agriculture and dairy-keeping with the goal of applying that knowledge to the villages surrounding the Santiniketan school. Rabindranath wrote, ‘If we can possess the science that gives power to this age we may yet win, we may yet live.’

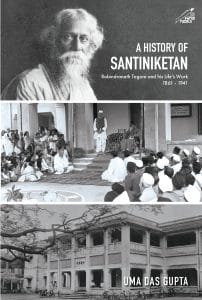

This excerpt from A History of Santiniketan: Rabindranath Tagore and his Life’s Work 1861-1941 has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.