Famous Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib once wrote, ‘Ik roz apni rooh se poocha, ki Dilli kya hai, to yun jawab main keh gaye, yeh duniya mano jism hai aur Dilli uski jaan (I asked my soul: What is Delhi? She replied: The world is the body, and Delhi its life).’

Delhi is a wonder in its own right – a microcosm of India encapsulated within a city. From the narrow, bustling lanes of Daryaganj and Matia Mahal to the opulent expanses of Greater Kailash, Delhi accommodates everyone, yet remains divided – not by caste, but by class. This class divide plays a pivotal role in Delhi’s politics, shaping electoral outcomes and governance priorities.

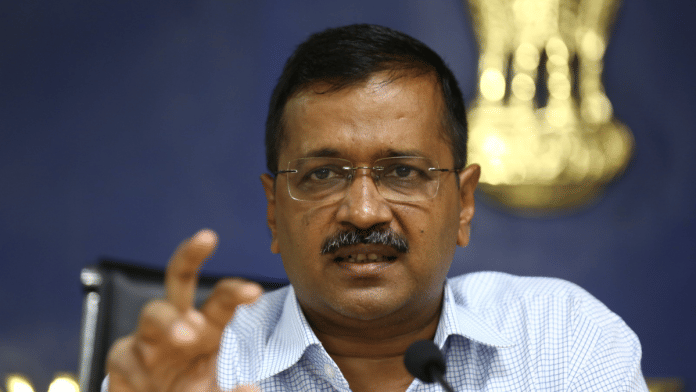

Former CM Sheila Dikshit strived to uphold the pluralism and modernism of Delhi. She worked relentlessly to improve the city’s infrastructure and garnered support across different classes. However, with time, the middle class (particularly the lower middle class) grew disillusioned with her governance. Enter Kejriwal, a middle-class professional who understood the socio-economic hierarchy of Delhi like no other. The AAP came to power and retained its hold by strategically appealing to the poor, lower middle class and segments of the upper middle class.

Governance in Delhi is unique in its immediacy – the city-state’s relatively small size means that government policies have a direct and tangible impact on its residents. The AAP’s early success was rooted in its focus on key public sectors and its well-crafted welfare policies. However, by the 2025 Delhi Assembly elections, the party’s governance record was under scrutiny. The anti-incumbency sentiment against the AAP after 10 years in power was at its peak. With the arrests of Kejriwal, Sisodia and other key leaders, the party struggled with a leadership vacuum. In their absence, Atishi, Saurabh Bharadwaj, Kailash Gahlot (who later joined the BJP), Gopal Rai and Imran Hussain attempted to manage governance while simultaneously campaigning against the arrests of their top brass. The result was

a glaring administrative failure.

Sanjeer Alam, associate professor at the CSDS, noted in the Lokniti-CSDS Delhi election survey: ‘The results of the 2025 Assembly elections show that the AAP lost more than two-thirds of the seats it had bagged in 2020.’

Also read: When a Delhi lawyer wasn’t recommended as a judge because his nickname was ‘Boozer’

An Anti-Kejriwal Election

After resigning as CM and securing bail from the Supreme Court, Kejriwal emerged from jail, declaring the Delhi Assembly election his ‘agnipariksha’. The entire campaign revolved around him, underscoring a clear message – the waning popularity of the AAP supremo.

Kejriwal’s declining popularity was not an overnight phenomenon. While the AAP’s own missteps played a crucial role, the BJP’s sustained narrative-building against him also contributed significantly.

Until 2020, Kejriwal was functioning smoothly, delivering on his promises and enjoying considerable public support. If we compare him with other populist leaders like Mamata Banerjee, Hemant Soren, M.K. Stalin, Yogi Adityanath or Himanta Biswa Sarma, a common factor emerges – their ability to deliver on schemes, even amidst challenges. Many of them faced opposition from the central government, yet they managed to implement their policies effectively.

Kejriwal, however, faltered in this aspect over time. While his contributions to education and healthcare remain undeniable, the past five years have seen a decline in these sectors. Many mohalla clinics shut down or ran out of medicines, and after Sisodia’s imprisonment, the AAP’s hallmark education reforms also lost momentum.

As mentioned before, at the heart of Kejriwal’s appeal was a threefold promise – good governance, honesty and his image as a ‘common man’. The BJP systematically dismantled all three. While the AAP blamed the central government and the LG for obstructing its work, the average citizen was less concerned with the reasons and more affected by the fact that progress had stalled.

Kejriwal’s arrest further eroded public confidence. Initially, many still believed he was not corrupt. However, as he faced repeated rejections of bail and a prolonged legal battle, public perception shifted. Unlike Hemant Soren, whose singular arrest allowed room for a conspiracy theory, the AAP saw multiple top leaders taken into custody in the liquor policy scam. Gradually, the belief solidified that the party that had once stood against corruption had itself succumbed to it.

The final blow came with the ‘Sheesh Mahal’ controversy (more on this later). Even those who were hesitant to accept the corruption allegations found their doubts shattered when the BJP strategically circulated videos showcasing Kejriwal’s opulent lifestyle. The footage was widely shared on WhatsApp, ensuring that no Delhi voter remained unaware of it. This narrative destroyed the very foundation of his ‘aam aadmi’ image. By the time elections arrived, public sympathy had evaporated and Kejriwal himself had become the focal point of voter resentment.

Ultimately, Delhi’s mandate was not a resounding endorsement of the BJP – it was an unmistakable rejection of Kejriwal.

Also read: There’s no statue of Begum Mofida Ahmed in Jorhat. She was 1st Assamese Muslim woman MP

Middle-Class Factor

The middle class of Delhi has historically played a crucial role in electoral victories. In previous elections, a pattern had emerged: while Delhi’s middle class voted for the BJP in the Lok Sabha elections, they leaned towards the AAP in the Assembly elections. In 2025, this trend shifted. Alam observed, ‘Compared to 2020, AAP’s support among the poor fell by 11 percentage points. Its vote share among the lower classes declined even more sharply – by 18 percentage points. Although the AAP saw a section of the middle-class voters also move away from it, it was among the rich that the party lost hugely.’

The CSDS data highlights a gradual shift in Delhi’s middle-class voting patterns. In 2015, the AAP secured approximately 55 per cent of the middle-class vote. By 2020, this figure had dropped slightly to 53 per cent, with the BJP’s support rising from 35 per cent to 39 per cent. This indicated a growing inclination towards the BJP among the middle class, forcing the AAP to recalibrate its strategy.

Recognizing this, Kejriwal made an unprecedented move before the 2025 Delhi elections – he released a ‘Middle-Class Manifesto’. This manifesto, accompanied by a seven-point charter of demands for the Union Budget, aimed to address the middle class’s economic concerns.

The key demands included a significant increase in education spending, urging the government to allocate 10 per cent of the budget to education (up from the current 2 per cent), capping private school fees and expanding scholarships. In healthcare, the AAP advocated for a 10 per cent budget allocation and the removal of taxes on health insurance. The manifesto also proposed raising the income tax exemption limit from ₹7 lakh to ₹10 lakh and removing GST on essential commodities. For senior citizens, it promised free medical services, robust pension schemes and a 50 per cent concession on rail travel.

By highlighting these tangible issues, the AAP sought to position itself as the party that understood and prioritized middle-class aspirations. However, the BJP, well aware of the significance of this demographic, played its trump card just days before the election. On 1 February (four days before polling), Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a massive tax relief: individuals earning up to `12 lakh annually would pay no income tax. This single move resonated deeply with the middle class and tilted the electoral balance in the BJP’s favour.

Ashish Bhattacharya, a 56-year-old banker from Chittaranjan Park, summed up the middle-class sentiment: ‘What was Kejriwal giving us? We don’t send our children to government schools, we don’t go to mohalla clinics, we always get electricity bills above 300 units, so we don’t get any relief. Our wives and daughters don’t travel by bus. Yet, our tax money was funding freebies for others. We were being used.’

This sentiment was prevalent across Delhi’s middle class. The AAP spokesperson Priyanka Kakkar, however, offered a different perspective: ‘It would be incorrect to attribute our defeat solely to the middle class. We lost by only a few percentage points to the BJP, which means we still enjoyed support across various sections for our work and honest governance.’

Echoing his concerns, 38-year-old IT professional Ritesh Verma from Malviya Nagar told me:

I voted for AAP in three consecutive assembly elections because I believed they were challenging the status quo. Even when the party shifted its focus to freebies, I continued to support them, as they were helping the lower middle class and the poor while ensuring basic services remained intact. But look at Delhi today – the roads are crumbling, drains are clogged, water shortages are rampant and pollution worsens every year. Despite AAP being in power in Punjab, they have failed to address stubble burning. Instead of governance, all we see is constant confrontation with the Centre. At this point, it seems more practical to have the same party ruling both Delhi and the Centre to ensure better coordination and essential services.

This excerpt from ‘The Aam Aadmi Party: The Untold Story of a Political Uprising and Its Undoing’ by Sayantan Ghosh has been published with permission from Juggernaut.

This excerpt from ‘The Aam Aadmi Party: The Untold Story of a Political Uprising and Its Undoing’ by Sayantan Ghosh has been published with permission from Juggernaut.