Will they declare now?’ Tony Greig bellowed, before more visuals of the dressing room drifted in. ‘Nothing, absolutely nothing. He’s leaving them out there. Ganguly is now dragging it out too long.’ The overwhelming fear, of course, was that the lack of a declaration was eating away into valuable time for the bowlers to bowl Australia out. But Ganguly remained stubborn, finally calling back the free-swinging pair of Zaheer Khan and Harbhajan a good seven overs after Laxman had fallen and 15 minutes after Dravid had departed.

Did the thought, then, ever cross his mind that the bowlers wouldn’t have enough time to pick up 10 wickets?

Ganguly laughed.

‘Even my father was getting upset with me, to tell you the truth. He was watching the game from the office of CAB [Cricket Association of Bengal], where he was vice-president. An hour before lunch on Day Five, I get a note from the dressing room attendant. It’s from my father. “What are you doing? Why aren’t you declaring? Don’t you want to win this Test match?” the note read. I tore it up and threw it away. He was certain that I had thrown away a golden opportunity to win.

‘But the only reason I prolonged the declaration was I believed we needed a lead of 370–380 runs against that batting line-up, considering we were going to bowl 70 overs on the final day against them. I did not want to get to a stage where the match could’ve slipped away; in India things change very quickly on the fourth and fifth days. I did not want the chase to get to a situation where I take the catching fielders away and put them in defensive positions.’

With a thicket of hands and legs all around the bat, India won with single-digit overs to spare after Harbhajan dismissed Glenn McGrath for his thirteenth wicket of the match, with a little help from Tendulkar’s right-arm all-spin, those variations getting rid of Gilchrist, Hayden and Shane Warne in one mesmeric spell. And Eden Gardens, cops and all, promptly combusted. Ganguly has maintained that it was the finest hour of his career, its era-defining meaning only heightened after India won the all-but-lost series in yet another thriller in Chennai.

‘Both my high point and low point came against the Aussies. Not winning the World Cup final in 2003, that still hurts,’ he said of the match in which he stuck Ponting’s Australia in to bat, and the captain responded with an unbeaten 140, taking Australia to a score of 359 before it was the norm and beating India by 125 runs. I had a question for him ever since the coin fell on the Wanderers pitch on 23 March 2003, and finally had the opportunity to ask it, so I mustered up the courage and let it fly.

I was expecting annoyance but he only shrugged. ‘No, not a blunder. I still think I made the right decision at the toss. We just didn’t play well enough—bowled too short on a pitch which offered a lot if the ball was pitched up.’

Although I had got what I intended from the interview, it would have been remiss of me not to have asked one of the most influential modern-day short-format batsmen about his exemplary ODI career. But with a rap on the door by one of the book publisher’s people, I was told my time was up and that the TV journalist Barkha Dutt, waiting her turn to interview Ganguly, had long arrived. I had been allotted fifteen minutes and had already taken fifty-five of Ganguly’s time. But he blinked his fingers at the door. ‘Please ask her to wait for ten more minutes,’ he said, then looked at me and raised a princely hand. ‘Carry on.’

So, I did. Was he aware that the game against Pakistan in Gwalior, 2007, would be the last time he represented India in blue?

‘I had no idea that it was. Not for a long time after that match and series had ended, to be honest. I had had a big year. I got more than 1200 ODI runs [1240 to be precise] in 2007. In fact, across both formats [1106 Test runs as well, at an average of 61.44]. After that ODI series against Pakistan, we played a Test series against them, and I scored a hundred in Eden Gardens in the first game. In the next match, in Bangalore, I scored a double hundred in the first innings and 91 in the second. I was in the form of my life.

‘Immediately after the Pakistan series, I went to Australia for the Test matches, and the terrific form continued there. But all of a sudden, I was told that I would miss the upcoming ODI tri-series [the CB Series in 2008] as I was not part of their 2011 World Cup plan. They thought I was too old—I would’ve been thirty-nine in 2011—for the short-format, and both Rahul and I were pushed aside.’

Strange, then, that a career encompassing 11,363 ODI runs was bracketed by neither a great welcome (in Brisbane, 1992), nor a suitable goodbye (in Gwalior, 2007). ‘Yes, that’s the way it goes. I wasn’t expecting to debut in Brisbane in 1992, and I surely wasn’t expecting to be dropped for four years after just one game. So, those 11,000-odd runs were scored in the space of ten years. That’s life. I’m just glad that I finished my Test career on a high—beating the odds to return after my former coach [Greg Chappell] had left me out in 2006; to get all those runs in difficult situations in 2007 and to finish in 2008 against Australia with a series win, a series in which I did fairly well and even struck a hundred.’

I had one final question. When India had won the 2011 World Cup at the Wankhede, I had watched Ganguly position himself by the boundary rope, just a short distance away from reporters Nagraj Gollapudi, Sharda Ugra and I. Then Dhoni clattered that winning six, and immediately I turned towards Ganguly, who was emotional, to say the least. Many years later, I now finally had the chance to ask him this question. As the very men he had fought for when they were establishing themselves, the team that he had helped assemble in its nascence, had finally won a World Cup, did it, then, feel like he had won that trophy as well?

A grin tore across his face.

‘I still remember I came down to the ground and stood by the boundary rope to see how it felt to win a World Cup. I was commentating at Wankhede Stadium when the producer told me that I needed to be on air when India wins the World Cup. And I said, “Sorry, no chance.” I was not going to do it. I told the producer, “I’ve listened to everything you have said so far, but I am not going to listen to you now.” I really wanted to know what it feels like to be on the ground when our boys have a World Cup trophy in their hand. And what an atmosphere it was down there! I get goosebumps thinking about it right now.

‘Yes, even though I had finished playing for the country, I felt that I was a part of it. These were my boys too. That evening, every Indian felt like they had won the World Cup. I was no exception.’

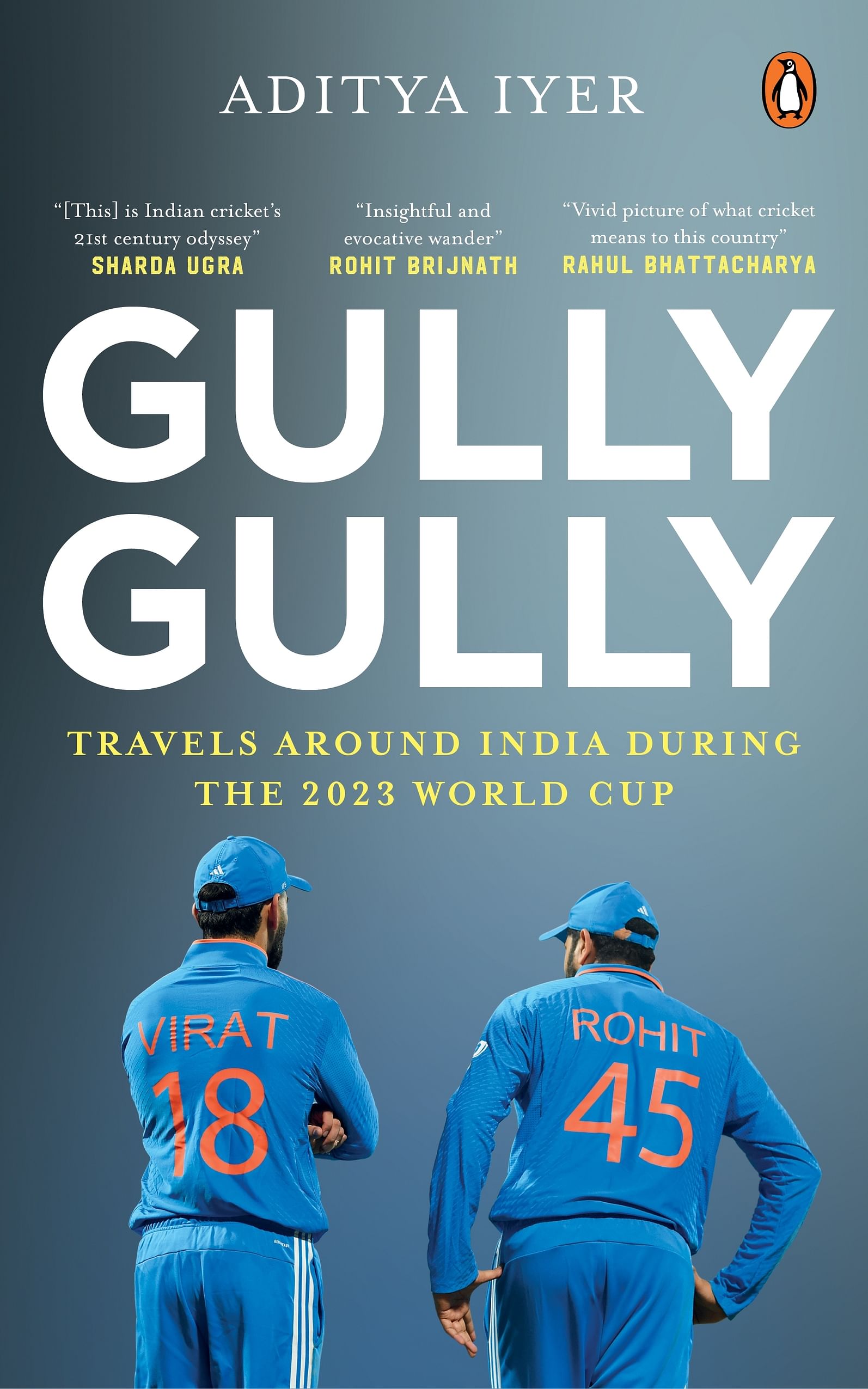

This excerpt from Gully Gully: Travels Around India During the 2023 World Cup by Aditya Iyer has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Gully Gully: Travels Around India During the 2023 World Cup by Aditya Iyer has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.