On 17 December 1921, we were busy making a football field for the madrassah, when the police came and arrested me under Section 40 of the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR) and took me to Peshawar jail. Instead of the lock-up, I was put in jail. After me, my other associates were also arrested. I was locked up in the cell where criminals are normally kept. When I entered the cell, a nauseating smell invaded my nostrils. Looking around, I saw a pan full of human excreta. I came out immediately and told the warden that it was repulsively filthy and that it should be cleaned. He replied curtly that this was a jail and that I should move into the cell at once.

Night and day, I was alone in this cell. My meals would be passed to me through the iron bars. Only when the addict sweeper of the jail would come to the cell to clean it, would its gate be opened, and when the cleaning was done, the gate would be locked again. At the time of cleaning too, a warden of the jail would stand over the head of the sweeper. The next day I found out that our other associates were also locked up in similar cells. Only Abdul Qaiyum Khan Swati and I were refused bail. When they realized that we were not prepared to pay bail, they removed us from these cells and took us before the deputy commissioner.

The deputy commissioner was a strange man, and so was the case against me. When the deputy commissioner asked as to what offence I had committed, he was told by the police that, for one, I had participated in the Hijrat movement and, for another, was now establishing free madrassahs. The deputy commissioner told him that if I had done the Hijrat once, then why was I allowed to return? I told him that, regretfully, they had not only taken over our land, but now they were not even prepared to allow us to live in it. On this, Sahib bahadur (the deputy commissioner) got angrier and directed his men to put me back in jail, sentencing me to three years rigorous imprisonment. Abdul Qaiyum Swati, too, like me, was sentenced to three years rigorous imprisonment.

Also read: What Bacha Khan’s daughter told me about his treatment by Pakistani authorities

The tale of the jail

You will recall that an article used to be published monthly on life in jail in the Pukhtun magazine under the title, ‘The Twentieth Century and I’. But due to my repeated arrests and due to my busy schedule, that subject was left incomplete. Since I was now confined in the jail at Hazaribagh and had no books to read, I thought that I should take advantage of this forced inactivity and make an effort to complete that article under the new title of ‘The Tale of the Jail’ (15 October 1931).

The condition of this jail was deplorable. The poor prisoners had to face many hardships. The staff was corrupt to the core and took bribes. Prisoners who had some money led a reasonably good life, while those who did not were miserable. The strange thing was that, in this jail, the darogha was not the one in sole authority; each employee had full powers, and each one ensured that his orders were obeyed. No one had any respect for the darogha; he had no authority, and no one obeyed him either. The reason for this was that he was an old man and was about to go on pension. The other reason was that he did not understand English. He had been promoted from a sepoy to a darogha, and the superintendent did not understand anything but English. So, the affairs of the jail were managed by the deputy darogha, Ganga Ram. The awe in which he was held was infinitely greater than that of the darogha. On account of this, the management of the jail was badly affected. When I was confined in the cell, a few prisoners from Peshawar came and said that they would bribe the darogha to take me out of the cell. But I told them that on moral grounds, I opposed the idea of giving bribes. That I was not a prisoner as such, but one who refused to provide surety for release on bail.

The food in this jail was inedible. The darogha used to pilfer, and the deputy darogha too had his share. I would grind grain in my cell. The chickpea that was given to me to grind was all weevilled and did not contain one grain that was whole. Its flour could not be sifted either, because then all that would remain would be the chaff. They would not bake bread from this kind of flour because its weight would decrease. Here, too, the poor prisoners were cheated. Bread baked from this flour could not even be held because it would break into small pieces and fall apart; so, it was held with both hands. I had never eaten chickpea flour bread and that too which contained more than 50 per cent impurities, on which one could not chew. With great effort I would eat only one piece… What can I say of the quality of its dal and spinach?

When someone falls sick in jail, he is taken to the hospital. But I was a political prisoner, there was no going to hospital for me. Only this badly lit, small room had fallen to my lot, in which I stayed all alone, day and night. The doctor would bring medicines for me here, and the superintendent would check on me once a month. After a few days I got better. I lost forty pounds in the one and a half months I stayed here. On account of a bad diet and lack of vegetables, I got pyorrhoea. My teeth got infected, my gums receded, and blood would ooze from them. Because of a poor diet, a disease had struck all the prisoners and four or five of them died almost each day. No one bothered to ask, because in the government of the British, a prisoner is not considered to be a human being and is treated like an animal. Nobody feels sympathy for the poor prisoners.

When the disease spread, the superintendent got worried and, for its prevention, would occasionally summon two or three other Englishmen for consultations. But the disease could not be controlled by consultations alone, and nor is this possible. The disease was the outcome of bad food and vitamin deficiencies and nobody bothered to investigate that aspect. Who was there to do so? The problem arose because of the corruption of the jail employees. Even the ration that the government had authorized for the prisoners was stolen from them. The superintendent was strange and totally unaware of what was going on. He was led in whatever direction his subordinates chose, because his eyes were shut to the realities of the situation.

On the day of the superintendent’s visit, he always made it a point to visit the latrines. That day would be a particularly trying one for the prisoners. Those who had loose stomach were greatly inconvenienced and humiliated, because once the latrines were cleaned, no one was allowed to use them until the inspection was over. If a prisoner had the urge to relieve himself, and had the courage to seek permission, he would run hurriedly to relieve himself. He would hardly have squatted, when the lambardar would be upon him. Sometimes he would ask for permission once or twice but instead of being given permission, would be humiliated. I have personally seen many poor prisoners who have relieved themselves in their trousers. Curses apart, this is that moment of humiliation which God may save everyone from. The British have enacted laws for us, but they are only meant to deceive the world. They are meant neither for them nor for their employees.

Also read: When India sent scores of prisoners to Iraq as sweepers during World War I

My sin in jail

Early one morning the superintendent and the darogha, Ganga Ram, entered my cell. The superintendent’s look and attitude towards me had undergone a change, and from his appearance it was clear that he was angry. In his hand he had a sheet of paper. He read it out to me, pointing out that under the jail rules, these constituted serious offences, and that he wanted to institute a criminal case against me. He had accused me of the following crimes:

‘You are a dangerous revolutionary and inciting others to revolution in the jail. You preach to the jail employees that service of the government is a sin. On account of your preaching, the sweeper of these cells has resigned from service. You carry out propaganda amongst the prisoners and make efforts to incite them to rebellion.’

I replied that I would say nothing about the institution of a case against me, and that he should proceed as he considered just and appropriate; that whoever had informed him of all this, had not reported the truth but spun a tale based on a web of lies and falsehood.

As to the other allegations, they were baseless. No doubt, I had preached but not for them to violate the rules of the jail, or to incite them to revolt. On the contrary, I had persuaded them not to fight amongst themselves and to peacefully serve their sentences – performing the labour assigned to them, and not to bribe anyone. Whenever this preaching brings about a diminution in the income of Ganga Ram and his employees, I am declared a rebel and an evil person. Then I told him that this jail was passing through a very bad time, and he was blissfully unaware of it all, and nor could he be informed about it. Even if he was informed, he could not bring about any reforms. That, the other night, he had come on his rounds. There was noise coming from a barrack; that he had gone and seen for himself what the quarrel and noise was about. Did he understand what this noise was about? I did not know what his staff had told him, but the fact is that the quarrel was over alcohol. I have not seen such corrupt and bad-charactered officials that I see in this jail. On my saying this, the man cooled down somewhat as his eyes were opened to the truth.

He told me that it would be best if I could give him a written response to the allegations levelled against Ganga Ram. I sent in my written reply, and later found out that he had summoned Ganga Ram and other officials to his bungalow and reprimanded them. But despite knowledge of all this, I was not taken out of the cell because they had warned him that if I were taken out, the prestige and honour of the government in general, and his, would suffer and the administration of this jail would be adversely affected.

When the news of my solitary confinement in the cell reached the other prisoners, they were provoked. I was put under strict security. I would send messages to the prisoners to be careful, as I knew full well the tyranny to which innocent prisoners could be subjected.

If the condition of a political prisoner and the circumstances in which he is detained in jail cannot be made known outside, who can get to know the conditions in which the other criminals are held! Anything can be done with them, even if they are to be burnt in a fire. I myself know full well, that if anyone wants to see the justice and civilization of the British, they should visit the jails.

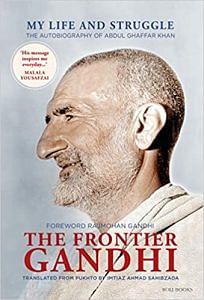

This excerpt from ‘The Frontier Gandhi’ a translation of the Pukhto ‘My Life And Struggle: The Biography of Abdul Ghaffar Khan’ by Imtiaz Ahmad Sahibzada has been published with permission from Roli Books.

This excerpt from ‘The Frontier Gandhi’ a translation of the Pukhto ‘My Life And Struggle: The Biography of Abdul Ghaffar Khan’ by Imtiaz Ahmad Sahibzada has been published with permission from Roli Books.