For a while, Nehru mostly ignored the young Jan Sanghi as a minor nuisance. But some things were unpardonable. Vajpayee occasionally travelled to Jammu and nearby areas in the valley, and returned to make passionate pleas in parliament to revoke Article 370. In mid-February 1958 Pir Maqbool Gilani, a key aide of Sheikh Abdullah, met and complained to the prime minister that he and other Kashmiris were not being given a permit to enter their home state by the Bakshi government, even as trigger-happy Jan Sanghis like Vajpayee ‘are allowed to go to Jammu and deliver objectionable speeches’.

Nehru immediately shot off a letter to the J&K chief minister Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad: Vajpayee was ‘a highly objectionable person’ who was capable of creating ‘much mischief in Jammu, and upset thereby the policy that you are following’.

That day he also separately wrote to the cabinet secretary Vishnu Sahay, asking him to ensure that the Jan Sanghi was in future denied permission to visit the Himalayan state: ‘I do not like men like Vajpayee being allowed free entry.’ The animosity between the two began to melt, at first inconspicuously, in the second year. This became apparent during a discussion on the international situation in mid-August 1958. While Vajpayee praised Nehru’s overall steering of the country’s foreign policy, he also mildly chided the prime minister for entangling himself unnecessarily in international events which had no direct repercussions for India.

We may like to keep ourselves isolated but events would take us in the grip. However, the question is whether we can discuss in some details the policy of keeping ourselves actually aloof from the disputes of other countries. One requires a voice to speak, but to keep quiet one requires both voice and wisdom. In the international sphere we have developed a tendency of speaking a little more than necessary, and it is my submission that we should practice the art of keeping quiet.

Vajpayee was referring to the recent coup in Iraq, which had overthrown the country’s US-backed monarchy. Suspecting a Soviet conspiracy, the western powers dispatched marines and troops to the area. Nehru felt annoyed to see the US and Britain ‘misread the situation’.

By thinking of developments ‘solely in terms of communism and anti-communism’, the Western powers had ignored the feelings of the Iraqi masses. Nehru warned them against intervening in Iraq, even as he agreed to the Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev’s suggestion of an immediate meeting between the premiers of the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, France and India, along with the secretary-general of the United Nations. The reaction of the Western countries was less than favourable; the meeting was shelved, and the issue was referred to the General Assembly. Vajpayee felt that Nehru’s haste to intervene created an impression that the Russians liked India, while the Americans did not: ‘In short, Russia, in her Cold War, made us a pawn in her publicity fight and we allowed ourselves to be used.’

To his credit, the prime minister did not take offence at being lectured on international relations by a first-term MP who did not yet hold a passport. Of late Nehru had himself been wondering whether being ‘a crusader on the world stage’ was taking too much of his time and attention away from the dire economic situation at home. He thanked Vajpayee for acknowledging that India’s foreign policy was on the right track, adding that he was in ‘complete agreement’ on the need to keep quiet unless India’s interests were involved.

At the same time, Nehru clarified that he was forced to intervene immediately as both sides were psyched for a confrontation in Iraq: ‘All the strategic plans were already there and the armies knew that they had to move from here to there to destroy a particular city and drop atom bombs at such and such place.’ With personal acquaintance, Vajpayee’s respect for the prime minister had grown. He noticed that despite the occasional fits of temper Nehru displayed in parliament, he was amazingly tolerant and unjudgmental towards opposition members.

For his part, Nehru did not mind receiving occasional praise and constructive advice from an adversary who was otherwise always gunning for him; the prime minister could also use the acquaintanceship to build bridges with this insignificant but most vocal of opposition parties. Nehru was beginning to think of Vajpayee as a likeable, bright young man in an otherwise regressive party. While they continued to bicker inside and outside parliament over matters big and small, personally they continued to be warm.

By the end of his second year in parliament, Vajpayee had stretched his limits as the leader of the four-member Jan Sangh. With time he had realized that the speech-making that impressed the crowd at party gatherings was less effective in the business of law-making. He had improved himself: his speeches now had a rhythm that parliament demanded – more pointed and coercive, desperate for immediate attention. But days of research on a subject, followed by patiently sitting all day – in the fourth or fifth row, with three other colleagues – awaiting his turn, depressed him. Sometimes, within the allotted time limit for a debate, his turn just didn’t come.

On others, when he got a chance to speak, his words would not influence the government’s decision. Some mornings he woke up and scanned the newspapers only to find that there was no mention at all of his speech that had been heard with attention in parliament the previous day. Was he slogging away in a vacuum? That said, Nehru never prophesied a prime ministership for Vajpayee. Nehru was upset with MPs like Vajpayee courting arrest in September 1958, only a few days after he had suggested that MPs of distress-affected areas go to their constituencies to help spread order. A month later, Vajpayee mocked Nehru’s proposal to exchange enclaves on the eastern border with Pakistan as ‘bhudaan’ – a gift of land.

‘The Constitution of India does not empower anybody to give away Indian land to others,’ he railed against the Nehru-Noon Agreement in parliament on 8 December: ‘We can annex territory belonging to others, but we cannot give away our land to others. Nobody, not even the Prime Minister, has the right to deprive any citizen of his nationality and citizenship.’ He threatened a country-wide agitation.

Despite opposition from Jan Sangh and socialists, Nehru went ahead with the transfer hoping to win Pakistan’s trust to solve the larger tangle in Kashmir. Speaking at a public meeting in Baroda on 2 November, Nehru noticed a small crowd of RSS–Jan Sangh activists waving placards opposing the Nehru-Noon Agreement. While Nehru wrote them off as the ‘only ones who can be trusted upon to be wrong on every issue’, he pointed out that even the Sangh Parivar had ‘some decent people’, wishing they had more such people. It was a qualifier meant for Vajpayee.

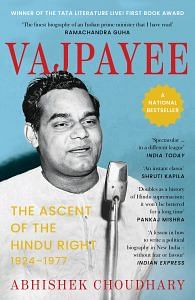

This excerpt from ‘Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924-1977’ has been published with permission from Picador India.

This excerpt from ‘Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924-1977’ has been published with permission from Picador India.