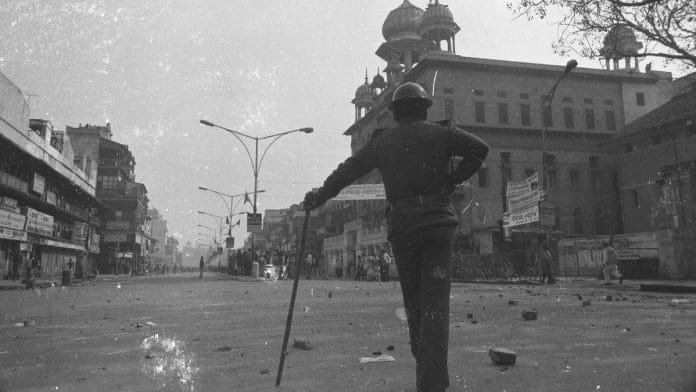

The fact that Mrs. Gandhi’s killers were Sikhs had wide and bloody ramifications for the community.

As the news reached Tihar, there was an alert of some Sikh inmates greeting the news of the killing with slogans like ‘Khalistan Zindabad’. To avoid the situation from turning volatile, we swooped in and immediately isolated them. Even before the assassins were brought to jail, Sikh prisoners were very fearful as they faced angry, murderous fellow inmates.

I felt terrible seeing what was happening in front of me. The Sikhs are one of the most patriotic and hard-working communities in the country and they were being vilified because of the actions of a few militants. But I do have a theory that I have long held – liberal Sikhs had stayed silent for far too long.

Militancy had raged for a long time and if they had taken a stand when it had first started in the early ’80s, we would not have reached where we were. In Tihar, the Sikh inmates who were in jail for terror-related charges were especially scared.

So, the first thing we did was to identify and seclude all of them. This meant that those who were lodged in bigger barracks (the ones that could have up to 200 inmates in one) were moved to either individual cells, or those that could accommodate three or five people. Some inmates were also shifted to high-security solitary cells.

Also read: What’s ailing Punjab’s jails — dreaded gangsters, understaffed prisons & idle inmates

Out on the streets, Sikh men and women were being burnt alive with petrol-drenched tyres thrown at them. Soon the Sikh prisoners realized that, despite guards, they were not entirely safe from this retaliation. Desperate SOS messages came to us from the prisoners as horror stories emerged of mobs burning Sikh homes and businesses while the authorities stood as silent spectators to the violence.

We gave strict instructions to all security guards for round the-clock vigilance and ordered that all visits to Sikh inmates had to be supervised. We needed all the manpower we had to protect the Sikh inmates from fellow prisoners and this is why we moved all guards who were previously stationed around the periphery of Tihar, indoors. Despite this, I cannot say that we were totally immune to the rioting that was happening outside our walls and there were reports of stray incidents of Sikh inmates being beaten up. I am not sure if this was done out of love for Indira Gandhi. I think some used the anti-Sikh atmosphere that was prevalent outside and in the country at the time to simply settle personal scores.

As it usually happens in a riot, there are some people who are just looking to benefit from the chaos and in this case some wily, petty criminals used it to defame us. There were a few isolated instances of some Sikhs being struck, but the word went out that we, the jail administrators, were forcing them to cut their hair. Some even complained that we were forcing them to smoke cigarettes, an absolute taboo for Sikhs. Journalists did not believe our denials and these reports were published in newspapers.

Even the act of segregation that we did in order to provide them security was misconstrued. The Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC) wrote to us to ask why we were exploiting Sikh prisoners, which is when we explained to them that most of those who had been complaining against us were petty criminals who had recently found the Sikh cause as a convenient one to benefit themselves. I could easily spot the troublemakers.

Also read: 4 commissions, 9 committees & 2 SITs – the long road to justice for 1984 Sikh killings

Petty criminals who were regulars in Tihar, started growing out their hair and wearing patkas or saffron scarves around their heads to look the part of Khalistan supporters. Why? First of all, because it was an exciting, subversive thing to be in jail at the time as it got you plenty of attention from the media. But more importantly, it was about the money. At that time, if you could establish that you were a Khalistani or a Bhindranwale supporter, you could potentially get funds from various supporters abroad. The more notorious you were in jail, the larger the donations came from such support organizations in the UK, US, or Canada. People like Harjinder Singh alias Jhinda, who we knew as a small-time thief went on to become a dreaded Khalistani terrorist in front of my eyes. He was always in and out of jail and never for anything more serious than assaulting someone, petty theft or cheating. Post 1984 he completely re-fashioned himself. We were agog when we heard that he was behind Congress leader Lalit Maken’s murder and later in 1986, he was the one who assassinated Army Chief General Arunkumar Shridhar Vaidya, who had led Operation Bluestar.

Harjinder may have found his Khalistani cause in Tihar. He was hanged for General Vaidya’s murder in a Pune jail in 1992. We heard rumours that certain families in West Delhi were giving shelter to sympathizers of the Khalistan cause. Of course, nothing was ever proved. Much more tangible was the impact that we saw inside Tihar.

I think it is for the first time in the history of criminal justice that the inmates themselves asked to be put in fetters or chains. Initially, when the requests came from those that had to appear in Punjab for legal hearings or other matters, we were intrigued.

Then we realized that it was because of the increasing number of militants that were being bumped off as part of the new ‘zero tolerance policy’ of the state. The textbook modus operandi for this was that when an inmate accused of militancy had to travel to Punjab for a hearing, he would be accompanied by Punjab police officials. It was not unusual to hear that en route the prisoner had ‘run away’, never to be heard of again. We soon figured that this was code for when they had met with an ‘encounter’ and eliminated. But if a prisoner submitted a formal request to be put in fetters, the police could not claim he had run away.

Also read: Anti-Sikh riots of 1984 were three days of furlough given to criminals by police, Congress

This request became very common in courts and soon enough encounter killings of this nature also reduced. Meanwhile, Sikhs in the Delhi Police were rounded up and went through intense grilling sessions to check for any proximity or sympathy towards Khalistani groups. We, in Tihar, also did not want to take any chances. It may be seen as discrimination on the basis of religion these days but all Sikh officers were removed from jail duty in anticipation of Indira Gandhi’s two killers being brought to Tihar.

I remember two names clearly – M.S. Ritu, who was the deputy superintendent and another official, B.S. Bhatia – who were removed from their jail duties. Two other Sikh employees were also removed and transferred to a social work department and administration. I am not sure if they knew why they were being moved or whether they were insulted that their loyalty was being questioned, but they submitted to the order without much fuss.

This excerpt from Black Warrant: Confessions of a Tihar Jailer by Sunil Gupta and Sunetra Choudhury has been published with permission from Roli Books.

This excerpt from Black Warrant: Confessions of a Tihar Jailer by Sunil Gupta and Sunetra Choudhury has been published with permission from Roli Books.