As the hostilities ramped up, India asked the Soviet Union to make a public announcement that intervention by any third parties—a reference to both US and China—could not but aggravate the situation in every way. The Soviets were reassured of India’s intentions, but did not wish to make any public announcement.

Nixon and Kissinger were now on tenterhooks. The Soviet Union was not stemming the war in East Pakistan. The new geopolitics involving China was confusing them. White House chief of staff Alexander Haig interrupted an Oval Office conversation on 12 December to say that the Chinese wanted to meet urgently. Kissinger thought this was totally unprecedented and felt ‘they are going to move’. Kissinger warned Nixon: ‘If the Soviets move against them [the Chinese], and we don’t do anything, we’ll be finished.’ Nixon asked, ‘So what do we do if the Soviets move against them? Start lobbing nuclear weapons in, is that what you mean?’ Kissinger replied, ‘Well, if the Soviets move against them in these conditions and succeed, that will be the final showdown.’ He added, ‘If the Russians get away with facing down the Chinese and if the Indians get away with licking the Pakistanis…. We may be looking right down the gun barrel.’

Nixon and Kissinger were both inaccurate and irresponsible in this reckless speculation. The Chinese had in fact sent a message to the US to the effect that they had carefully studied the options and felt that the Security Council should reconvene and push for a resolution calling for a ceasefire and mutual withdrawals. They were thus favouring diplomatic rather than military action. There was not a word about moving against India. Or a posture against the Soviet Union. Kissinger’s gambit with China to check the war had failed. The Chinese had refrained from acting because they were not inclined to militarily back Pakistan, they did not want to aggravate their problems with India and push it closer to the Soviet Union. India’s diplomacy was also working. Indira Gandhi had written to China the previous day seeking its understanding of India’s predicament and asking Zhou to exercise his undoubted influence on Yahya to acknowledge the will of the Bengalis.

With both the Russian and Chinese gambits having failed, and its appetite for direct intervention lost, the US reluctantly directed its attention to multilateral diplomacy at the United Nations. On 14 December, the Soviet leadership sent a message to Nixon that, ‘we have firm assurances by the Indian leadership that India had no plans of seizing West Pakistan territory’. The same day, a draft resolution came up in the Security Council, tabled by Poland, then a Soviet proxy, outlining conditions of the ceasefire.

Before the resolution came to the Security Council, Yahya Khan spoke to Bhutto on the telephone and told him that the Polish resolution looked good: ‘We should accept it.’ Bhutto had replied, ‘I can’t hear you.’ When Yahya repeated himself several times Bhutto only said, ‘What what?’ When the phone operator in New York intervened to inform them that there was nothing wrong with the connection, Bhutto told her to ‘shut up’. Clearly, Bhutto had no intention of following Yahya’s instructions. Bhutto went on to make a moving speech at the Security Council meeting and closed by declaring, ‘I will not be a party to the ignominious surrender of part of my country. You can take your Security Council. Here you are. I am going.’ Bhutto then tore up the resolution papers with a dramatic flourish and stormed out of the meeting. That spelt the end of the Polish resolution. Bhutto’s decision to walk out of the UN triggered Pakistan’s surrender on the battlefield and a decisive victory for India.

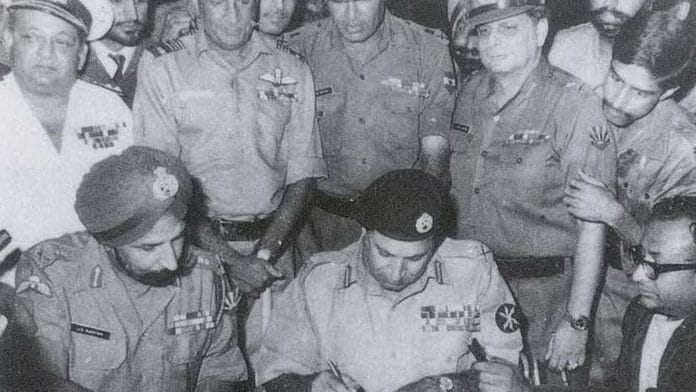

The war ended at 4.55 p.m. on 16 December, thirteen days after it began, when in Dacca, General Niazi unbuttoned his epaulettes, removed his revolver and handed it to Lieutenant General J. S. Arora. He then went on to sign the Instrument of Surrender. The speed and scale of the operation made the victory decisive. India held 93,000 prisoners of war.

The same evening, India announced a unilateral ceasefire on the western front, effective from 17 December.

The eventual outcome was influenced by chance and circumstance; it was not what the planners began with. The contingency plan drawn up by the Indian Army did not specify the capture of Dacca as the military aim, nor did the subsequent modifications to the war plan identify it as the main objective or earmark resources for each capture.

Had Bhutto accepted Yahya’s advice and accepted the UN resolution, Pakistani troops may not have needed to surrender. Bhutto seems to have played a larger and more clever game. Military analyst Raghavan plausibly observed:

Singed by his experiences with the military, both under Ayub and Yahya, Bhutto seems to have concluded that the new Pakistan must be built on the ash heap of the army’s decisive defeat. He was not wrong. Bhutto’s decision to walk out of the Security Council saved the day for India and precipitated the ceasefire, leading to a decisive and unambiguous victory for India.

For the Americans, the creation of Bangladesh was a done deal and the saving of West Pakistan was the illusion of success they created. For Indira Gandhi, it was unthinkable for India to enter West Pakistan where it had no political base, as against Bangladesh, where it had political allies in Mujib and his forces.

‘It’s the Russians working for us,’ said Nixon when he met Kissinger.

‘Congratulations Mr President,’ said Kissinger, ‘you have saved West Pakistan.’ Writing their respective self-congratulatory memoirs later, both Nixon and Kissinger claimed credit for saving West Pakistan. ‘By using diplomatic signals and behind the scenes pressures,’ wrote Nixon, ‘we had been able to save West Pakistan from the imminent threat of Indian aggression and domination.’ Kissinger went a step further, ‘There is no doubt in my mind, that it (the declaration of ceasefire) was a reluctant decision resulting from severe pressure which in turn grew out of American insistence, including the fleet movement.’

This excerpt from Ajay Bisaria’s book ‘Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan’ has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.

This excerpt from Ajay Bisaria’s book ‘Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan’ has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.