Chain-stitch embroidery did not originate in India; the earliest surviving evidence for its use is in China in the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), with superb examples recovered from a tomb at Mashan in Hubei Province and also from the Pazyryk tombs in the Altai Mountains. Whether the use of chain stitch in India is an independent development or was introduced from China is not known. Chain-stitch embroidery is not the exclusive preserve of Mochi embroiderers in India and its use is not confined to western India: embroideries from Bengal also use the stitch, often leading to controversy over their origin. A group of embroidered hangings made for export to Portugal, often with figurative motifs on a dark blue silk ground, has sometimes been attributed to Gujarat purely on the basis of the use of chain stitch, whereas earlier, undisputedly Bengali export embroideries also relied heavily on the stitch for both outlining and in-filling of motifs.

At what date the Mochi community started embroidering on cloth rather than leather is an unresolved question. It seems undisputed that the skill was learned from Sindhi leather embroiderers (whether in Sindh itself or in Gujarat), and the comments of Barbosa and Linschoten from the 16th century noted above, suggest that the art of embroidering on cloth was already well advanced by that time, although Barbosa’s remark that the embroidered quilts and bed-hangings that he so admired in Cambay were made by ‘Moorish [i.e. Muslim] washerwomen’ suggests that a quite different community may have been responsible, as Mochi embroiderers would have been Hindu men rather than Muslim women.

Some oral traditions of the Mochis state that a Muslim fakir (holy man) from Sindh taught the Mochis the art in the mid-17th century: this is the version given in the 1880 Gazetteer of Bombay Presidency (see Ch.2, p.35). But other versions, such as that recounted by Prof. L.D. Joshi in an article of 1966 in the Gujarati journal Pathik, state that the transfer of knowledge from Sindhi to Kutchi craftsmen occurred during the reign of Maharao Desalji of Kutch (r.1718–41). This version of the story of how the Kutchi artisans secretly learnt the art of embroidery is worth quoting in full:

During the time of Maharao Desalji, Sindhi artisans were invited to embroider as well as repair the royal tents. The idea sparked in the mind of the Raoshri that, if this art is learnt by craftsmen from my kingdom, it would enhance the prestige of the realm. Kutch’s connoisseur king mooted the idea before his artisans. Till this time, there was no awareness of this art in Kutch. Royal tents were made of silk on which embroidery was done with very costly zari-cording. This expensive work was done in great secrecy by Sindhi kaarigars (artisans). They would keep the tent closed so that no one could learn their art.

A desire awoke in the hearts of Raoshri Desalji and his queens to bring this art to their land. They gave encouragement, declaring themselves as patrons. Soon enough, the skilled artisans of Kutch came forward despite being denied any help from the Sindhi craftsmen. The Kutchi craftsmen vowed they would pursue till they have learnt and mastered the technique relying on their own wit and skills. In the tent where the Sindhi kaarigars were secretly at work, entry was strictly forbidden. The plucky Kutchi kaarigars found a way out—they would drive tiny holes into the tent cloth and glimpse the design from a distance with one eye till they could learn the technique of Sindhi workmanship as it took shape on the tent walls. With abundant patience and painstaking labour, they dispossessed the Sindhis of their art. Thereafter, the art flowered with Kutchi talent and dexterity. Within a short time, the Sindhi artistry appeared coarse before the finesse and fineness of the Kutchi stitch-craft.

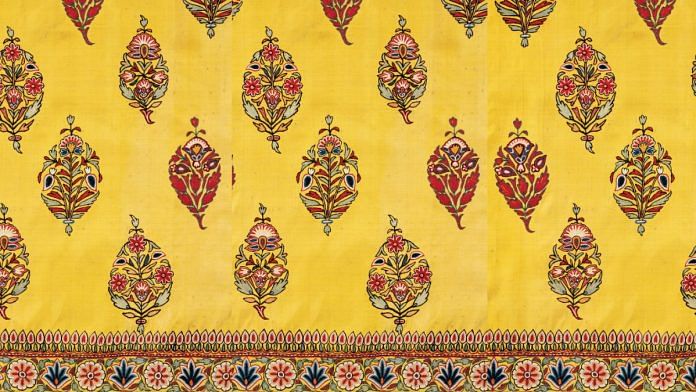

Today, with the exception of Kutch, nowhere else is work of such refined delicacy made. The kaarigars of this art can largely be found only in the towns of Kutch. The embroidery of Kutch in general is rarely mentioned by Western travellers; one exception is Marianne Postans Young, whose book Cutch, or Random Sketches taken during a Residence in one of the Northern Provinces of Western India (published in 1839) includes a brief paragraph describing aari work and praising the embroiderers, who ‘display much taste in their native designs.’

This excerpt from The Shoemaker’s Stitch: Mochi embroideries of Gujarat in the TAPI Collection by Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from The Shoemaker’s Stitch: Mochi embroideries of Gujarat in the TAPI Collection by Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.