India has a population of 1.3 billion. Its demographic mix itself is daunting: over 4,635 communities, 78 per cent of which are not only linguistic and cultural but social categories. Its religious minorities constitute 19.4 per cent of the population, of whom Muslims account for 14.2 per cent. The human diversities are both hierarchical and special. The de jure ‘we’ is, in reality, fragmented and divided by yawning gaps that remain to be bridged; hence the need for social cohesion and inclusion.

There is talk at times of Greater India and of the glory of a distant, imagined past. Will this, in terms of territory or population or both, assist or hamper this process?

According to the Annual Report of the Ministry of Home Affairs, India has 15,106.7 km of land border and 7,500 km of sea border. A feature of our land borders is that major or minor points of contention have persisted with regard to borders with Bangladesh, China and Pakistan, and attempts to resolve them continue with many limitations and varying degrees of success. This, consequently, has remained a significant challenge in the conduct of foreign relations with neighbours and has at times resulted in armed conflicts with varying results. The alternative, of a meaningful framework for effective cooperation on the basis of equality and mutual benefit, is yet to crystallize.

Either way, national security within existing borders becomes the first objective of foreign policy. The wherewithal for it is the national security apparatus to counter formal and nonconventional threats. This cannot be so in isolation since India is part of the global community and contributes to its ideals and objectives. Hence, importance is attached, since its inception, to diplomacy and the structure and activities of the United Nations and other multilateral agencies.

Any set of policies have two ingredients: principles and practices. The principles of Indian foreign policy were spelt out in early years and were focused on non-alignment with power blocs and autonomy in decision-making. Problems with neighbours of necessity assumed primacy but not at the expense of wider issues of global concern—war and peace, regional conflicts, decolonization in Africa—and in each of these India played a role of significance. The Korean War and the role played by Nehru to end the war is an early example. President Truman’s comment on it is noteworthy: ‘Nehru has sold us down the Hudson. His attitude has been responsible for us losing the war in Korea.’ In a sense, India defined itself in opposition to the Cold War and focused its international energies on the Non-Alignment Movement.

Today the global scene stands transformed. Two decades of the 21st century have witnessed changes in power structures. As with earlier bipolarity, unipolarity too has collapsed. The United States, despite the size of its economy and technological superiority, is a retreating power. Europe has discovered its strength in a non-homogenous European Union. The Soviet Union has been replaced by Russia and a number of its erstwhile units are seeking their own place in the sun, unsure of their affinity to the former arrangement. The Arab world, linguistic affinity apart, hardly agrees on any core unifying agenda. Israel has succeeded in securing its place in the sub-region.

For us, the priority has to be immediate proximity. China is a neighbour with whom we have a long border with disputed segments as well as environmental issues of a complex nature. It is militarily and economically stronger. There have been periods of military confrontation followed by commitments to maintain the status quo. There exists a vibrant trading relationship, adverse yet beneficial to segments of our economy.

Also read: Goan bakers brought bread to Mumbai. Then passed the mantle to Iranians

China’s economic progress is dazzling; its political structure and social cohesion are impressive. Its plans to expand influence on land and sea are at times unnerving. Yet, the outside world is barely aware of its diversities and its domestic tensions. It is nowadays felt that in view of new challenges, particularly in maritime security, India’s active participation in Quad would accrue strategic benefits. Here, two questions arise. What is the nature of threats faced by us and to what extent will it be addressed by Quad? Secondly, would it enhance or lessen our freedom for strategic options?

Another obvious example is Pakistan. Here the subjective is as relevant as the objective. The legacy of 1947 and perceptions emanating from it remain relevant in varying degrees with actors and spectators, and has caused occasional glee and more frequent sorrow. Despite political and economic disparities, it is a nuclear power and uses this status to its benefit.

Other areas of tensions relate to water and boundary disputes with Bangladesh and the complex question of Tamil citizens of Sri Lanka. None of these have been resolved and all remain subject of patient negotiations within frameworks of commitment to cooperation for mutual benefit. A complex set of considerations influence relations with Nepal.

In a wider sense, the global order has changed and thrown up new challenges. The expectation that the UN system will become more democratic and egalitarian has not materialized but new platforms for focused cooperation on a range of matters relating to human survival have come forth and nations are being compelled to participate in them seriously.

While priorities in foreign policy of any country cannot be done sequentially, precedence or ordering is unavoidable, more so because problem areas are seldom single-issue ones. The same holds for problems that transcend national borders and are regional in nature. Thus, with neighbours, matters of war and peace and human survival cannot be deferred or put on the backburner. In each of these and in actual practice, a nation’s own ideals on bilateral or global problems inevitably play a role.

Policymaking begins with specific, immediate and mediumterm objectives. A developing country like India seeks external assistance, technology and technology transfer, and expertise in different ways and at different times. These have to be identified along with resources. Thereafter, they get moulded in a policy framework and pursued through professional and political initiatives. Room is made for setbacks and the challenge at all times is to accommodate setbacks in a wider framework of continuing cooperation.

India is a status quo power and does not seek territories of others. It is also committed to working for a peaceful world and a peaceful South Asia. Doubts about these commitments are sought to be raised by some, relating to the happenings of 1947, to our being the successor state to the British Indian Empire, to our ‘map or no map’ statement, and to the stages through which a boundary problem became a boundary dispute with unfortunate consequences.

Recent happenings worldwide have shown that problems beyond human and governmental control have arisen on account of pandemics, water resources and environmental degradation and climate change. None of these can be addressed nationally; each requires united global responses, each needs to transcend traditional patterns of voluntary commitments, and instead be based on maximum capacity commitment. New technologies must not be monopolized.

The five big ideas for foreign policy should therefore be related to the following: (i) national security with regional boundary and water disputes, (ii) regional cooperation, (iii) pandemics, (iv) environmental degradation, and (v) climate change. The foregoing should not be seen as the rant of a pessimist but a realistic reading of the present and the foreseeable future.

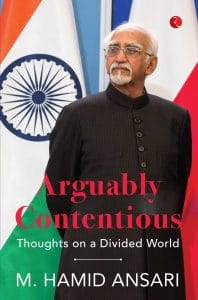

This was an address delivered by the former Vice President of India on 30 May 2021, organized virtually by the Council for Strategic and Defense Research in New Delhi.

This excerpt from ‘Arguably Contentious’ by Hamid Ansari has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from ‘Arguably Contentious’ by Hamid Ansari has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.