The Round Table Conference ended in a shambles in February 1931, two months after it began, hopelessly divided on issues of electoral representation and the system of election, communal interests, and the allocation of seats for election. The absence of the Indian National Congress, which was spearheading the struggle for freedom on the ground, also cast doubt on the relevance of the proceedings. The British responded by releasing Mahatma Gandhi and other detained Congressmen, and a ‘pact’ between the viceroy, Lord Irwin, and the Mahatma decided that the latter would suspend his civil disobedience movement and attend a reconvened Round Table Conference later that year.

Ambedkar then called on Mahatma Gandhi in Bombay, but this first meeting, in August 1931, was not a success. When Ambedkar entered the room, it took some time for the Mahatma, who kept conversing with others, to notice him. Ambedkar wondered whether he was being deliberately insulted. Then the Mahatma spotted him. He remarked that he had gathered that Ambedkar had a number of grievances against him. But he should know that ‘I have been thinking over the problems of Untouchables ever since my school days. I had to make enormous efforts to make it a part of the Congress platform. The Congress has spent not less than 20 lakhs on the uplift of the Untouchables.’

Ambedkar responded with his characteristic bluntness that the money had been wasted since it had provided no practical benefit for the uplift of his community. The Congress could have made rejection of untouchability a condition of membership, as it had done the wearing of homespun khaddar. But there had been no real change of heart on the part of the Hindus and that is why the Depressed Classes felt they could not rely on the Congress, but only on themselves, to resolve their plight. The Mahatma tried to mollify Ambedkar, hailing him as ‘a patriot of sterling worth’ in the struggle for the homeland. ‘Gandhiji, I have no homeland,’ was Ambedkar’s famous reply. ‘No self-respecting Untouchable worth the name will be proud of this land.’ He went on: ‘How can I call this land my own homeland and this religion my own wherein we are treated worse than cats and dogs, wherein we cannot get water to drink?’ The Round Table Conference, he added, had given recognition to the political rights of the Depressed Classes. What was the Mahatma’s view of this?

Also read: Columbia University teaches Ambedkar’s biography, but few in India have even read it

Gandhi’s reply was uncompromising: ‘I am against the political separation of the Untouchables from the Hindus. That would be politically suicidal.’

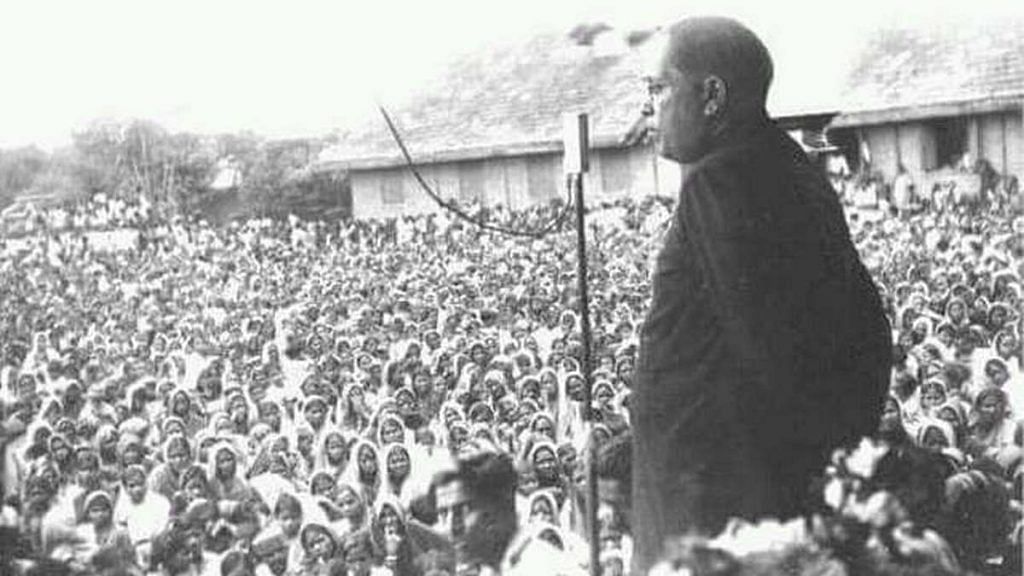

At about the same time, Ambedkar scored a personal triumph when the Bombay Presidency announced that it would open police recruitment to the Depressed Classes, something he had been ceaselessly calling for. And when invitations were issued to the second Round Table Conference (from 7 September to 1 December 1931), this time including pre-eminent leaders like the Mahatma himself and the Muslim League’s Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Ambedkar was not only prominently included, but he was asked to wield the pen for the drafting of a potential future Constitution for India. Unfortunately, Ambedkar’s health again laid him low: fever, diarrhoea, and vomiting prevented him from leaving for London at the same time as the other delegates, and he arrived in mid-September just as discussions had begun to heat up. The Federal Structure Committee of the conference was the venue for a pair of speeches by the Mahatma and Dr Ambedkar that were a portent of things to come.

The Mahatma spoke of the Indian National Congress, with its diverse and all-inclusive membership, as the sole representative of all Indian interests, classes, castes, faiths, and regions (and also of both genders, pointing to its several female presidents, something no other party could boast of). Ambedkar spoke of two themes in particular, the specific problems of the Depressed Classes and the future constitutional dispensation of free India. On the former subject, Ambedkar refused to be patronized. He disagreed openly with the Mahatma’s stand that no special provisions were required to cater to the needs of his community. When Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya (founder of Banaras Hindu University and a prominent Congressman) remarked that if the British had devoted enough resources to the eradication of illiteracy in India, there would have been no Depressed Classes to speak of, Ambedkar testily pointed out that his own extensive academic qualifications had made no difference to his being treated as an ‘untouchable’.

Also read: This leader forced Mahatma Gandhi to change his views on caste

On the latter subject, he clashed with the representatives of the Indian princes in his demand for elected representatives from the princely states. The maharaja of Bikaner, Sir Ganga Singh, pointedly said that the traditional rulers could not be expected to give the nationalists a blank cheque; Ambedkar responded bluntly to the effect that sovereignty resided with the people and not with their rulers, whereas the Mahatma assured the princes that the Congress had no intention of interfering in their internal affairs. (In this, Ambedkar’s view was to prevail over the Mahatma’s; before the decade was out the Congress had established a States People’s Conference to fight for the rights of the people of the princely states, with a unit in each state.)

Even though Gandhi and the Congress agreed with Ambedkar on several measures to counter caste discrimination—such as political reservations, temple entry, inter-caste dining and intercaste marriages, eradication of untouchability, greater educational and employment opportunities—from Ambedkar’s point of view it made perfect sense to stand apart from Mahatma Gandhi on the issue of the rights of the Depressed Classes. His reasoning was that had he opposed the British and sided with Gandhi, he would not have gained anything for his people from the British, while Gandhi, judging by the Congress’s track record thus far, would not, in Ambedkar’s view, have given his people anything more than pious blessings and hollow platitudes.