From the very beginning of the Great War, there was the ever-present risk that Germany would resort to chemical weapons, and this risk soon developed into a permanent threat for the foot soldiers on the front line across Europe. That threat became a reality when the first major gas attack was launched at the end of January in 1915. Germany’s Ninth Army released 18,000 gas shells on the Russian lines at Bolimov in what is now Poland.

The German commander, General Max Hoffman, watched the operation from the tower of a church that overlooked the battlefield. He found it hard to believe what he was seeing. The gas, a form of tear gas, appeared to have little effect. The German scientists who had created the gas failed to investigate how it reacted in the bitter cold of winter. In fact, the gas froze, the Russians appeared bemused and the gas attack proved a miserable failure. From his lookout, General Hoffman watched in disbelief, humiliated and very angry.

Shamed but undaunted, the scientists, headed by the Jewish chemist Dr Fritz Haber, who had led the way in synthesizing ammonia (for which he would be awarded the Nobel prize for Chemistry at the war’s end) went back to their laboratories. Haber with his shaven head, neat moustache, pince-nez and carefully buttoned white lab coat drove his team hard and, within a couple of months, had refined his chlorine gases and the canisters that would deliver them. The German High Command was delighted. Haber’s wife Clara was appalled. She too was a scientist and was idealistically opposed to science being used to develop such horrific weapons. She implored her husband to disband his development work, and when he refused and proceeded to come up with still more lethal gases, she shot herself through the heart with her husband’s revolver. For Haber, the survival of the Fatherland was more important than the death of his wife and he took himself off to see his latest chemical weapons in action. (His lengthy and highly complimentary biography on the Nobel Prize website manages to reduce his work on the poisonous gases, which killed tens of thousands of allied soldiers to ‘he organized gas attacks and defences against them.’ His son, by his marriage to Clara, followed his mother by committing suicide.)

Also read: This forgotten pilot from India was just 19 when he shot down 9 German planes during WWI

It was a very different story when the Germans dropped Haber’s new pressurized gas cylinders on French Algerian troops at the beginning of the second battle for Ypres in 1915. The attack was launched at sunrise in late April. As the 5,700 cylinders exploded, releasing hundreds of tons of chlorine, a yellow-green cloud of gas drifted across the allied trenches. The French were unprepared and unprotected. Five thousand died from asphyxiation within 10 minutes of inhaling the gas; others were temporarily blinded and experienced difficulty with breathing. In the confusion, advancing German troops equipped with rudimentary gas masks took 2,000 prisoners. A Canadian medical officer, who was also a chemist, quickly identified the gas as chlorine and recommended that the troops urinate on a cloth and hold it over their mouth and nose. Up till now, the coconut was still in the wings. But its time would come.

The attack caused outrage: ‘Devilry, thy name is Germany,’ howled the Daily Mirror. The commander of the British Expeditionary Force, Sir John French, described the use of gas as ‘a cynical and barbarous disregard of the well-known usages of civilised war’. But within four months, Sir John was changing his tune: ‘Owing to repeated use by the enemy of asphyxiating gases in their attacks on our positions, I have been compelled to resort to similar methods.’

The threat of gas did as much damage psychologically to soldiers on the front line as it did physically. It created a sense of terror, which, for many men, was greater than the terror of bullets and bayonets. Professor Edgar Jones of the King’s Centre for Military Health Research in London identified many cases where the fear of gas had spread from one platoon to another with devastating effect. Adolf Hitler, as a young corporal, was so terrified of being gassed he left the army for politics.

The first substance designed to offer protection against chlorine and phosgene gases was activated carbon from the charcoal of red cedar. But this did not work against the gases most likely to be deployed. Almonds, Arabian acorns, grape seeds, Brazil nuts, Chinese velvet beans, coffee grounds and peanuts were all reduced to carbon, tested, but found wanting. Enter the coconut. Hindu documents dating back to 450 BC refer to coconut charcoal filters being used as water purifiers. In many parts of the developing world south of the equator, the woody shell is burned as fuel. And while the charcoal created was of little interest to the people of the South Seas, it did interest scientists in Europe and America. First to identify the adsorption properties of powdered charcoal was John Hunter, working at Queen’s College in Belfast in the 1870s. He discovered that powdered coconut charcoal presented extraordinary powers of gaseous adsorption. By the turn of the century, Raphael Ostrejko, a chemist born in Latvia of Polish parents, was working on a process that would considerably increase the charcoal’s adsorption powers. Ostrejko passed steam at high temperatures through the powdered charcoal and found the adsorption powers of the charcoal were increased by 100 per cent.

Also read: The British used ‘low-caste’ Indian soldiers only when WWI intensified, rejected them after

A factory in Stockerau in lower Austria went into production, calling their activated charcoal Eponit. Although the tiny pores on the surface of activated charcoal are less than 4 nanometres in diameter, they greatly increase the surface area of the powder – four capsules of activated coconut charcoal would cover a football pitch. The pores trap molecules of a wide range of toxins, including chlorine and 2-chloroethyl sulphide, the gas commonly known as mustard gas. This property made coconut charcoal attractive to chemists looking for the most effective ways of filtering poisonous gases.

‘We have been using activated carbon to remove toxic gases for a century or more,’ notes Gregory Peterson, leader of today’s gas mask filtration research group at the Edgewood Chemical Biological Centre in Maryland. ‘Coconut charcoal exhibited the additional qualities of being chemically stable and therefore remaining active for long periods; it was resistant to abrasion and offered protection against a wide variety of gases.’

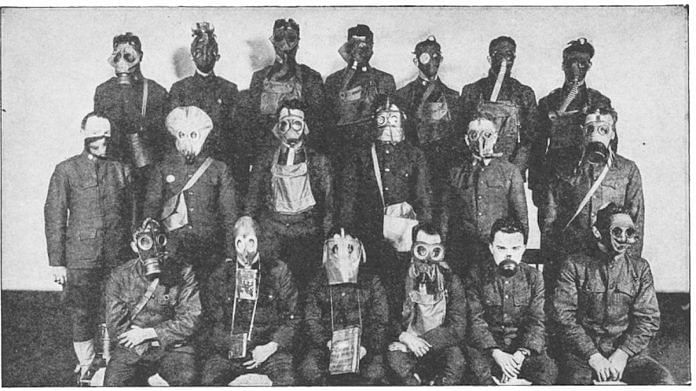

But few ever thought that poisonous gases would be used as a weapon of war. So following the chlorine gas attacks at Ypres, scientists and engineers in the UK and in the US had to go into overdrive in their search for an effective mask. While a number of researchers claim to have been the first to link the activated coconut charcoal with wartime gas attacks, it seems likely that Nikolai Zelinski, a senior organic chemist at the university in Moscow, prompted by the gas attack on Russian troops at Bolimov, was the first to stuff the charcoal into the filters of gas masks. Defence establishments in Europe and America were quick to follow his lead.

In the US the search for used coconuts began in earnest with the gas defence division of the Chemical Warfare Services writing an open letter to the Franklin Baker Coconut Company. ‘We are finding it difficult to secure a sufficient quantity of coconut shells to meet our requirements,’ the letter began. It explained that the ‘best material that has been found for gas masks’ was likely to run short if sufficient coconuts could no longer be imported.

The letter was incorporated in an advertisement in women’s magazines encouraging housewives to use recipes that included coconut, and then make the shells available for collection by government agencies.

Also read: Indian govt official writes to Harvard, wants prof to retract ‘coconut oil pure poison’ remark

The advertisements helped, and tons of coconut shells were delivered to government collecting stations and sent on to the Edgewood Chemical Biological Centre at the US Army’s Aberdeen proving ground in Maryland. But this still was not enough, and a charcoal plant was established in the Philippines (still an American colony at the time) with agents scurrying across South-East Asia, buying up huge quantities of coconut shells.

A similar plea for coconut shells was issued in Britain by the National Salvage Council after the large quantities of coconuts imported from Ceylon still failed to meet the demand from mask manufacturers. Thousands of women toiled long hours in factories large and small that had turned from producing peacetime goods to making gas masks. At Melksham in Wiltshire, the Avon Rubber Company which had produced pneumatic bicycle tyres, tennis balls and tyres for Rolls Royce cars, switched to manufacturing gas masks.

By the end of 1939, 36 million masks had been distributed in Britain. The government believed that war would be certain to mean gas attacks from the very start of hostilities. While the gas attacks never materialized, the fear engendered by the possibility that every air raid could be the one to bring blinding, choking, asphyxiating gases meant the masks provided comfort and vital psychological assurance for every man, woman and child. Without the masks, the morale of the civilian population would have been tested beyond endurance.

This excerpt from Coconut: How The Shy Fruit Shaped Our World by Robin Laurance has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from Coconut: How The Shy Fruit Shaped Our World by Robin Laurance has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.