I enjoyed the ordinariness of being nobody in a new place. After observing the musical sounds of the gushing waters, marvelling at its iridescent emerald colour and dipping a toe in its icy fingers, I headed for Mohan Sweets. As I walked away, I watched a boy toss a rope with a magnet tied to it. It pulled in coins from the shallow end. Magic. The salty smoke of deep-frying puris and samosas, shiny orange jalebis, with tea on the side—the classic Indian breakfast had tourists clambering to spot a table.

I stood out and ate at one of the standing tables, where uncles park their toddlers to reserve the space. An aunty with tennis shoes peeping out of her baggy blue salwar stood alone, biting into a hot samosa. She smiled at me and small talk began. She said she was here with her family. They were at another shop behind this one. She wanted samosa and jalebi. I said as little as possible, keeping the chat brief about being advised to eat here. She listened patiently and as she moved away casually after polishing off everything on her plate, she washed her hands at a water dispenser and said, Koi zaroorat ho to batana. If you need anything, let me know. She left with a head tilt as goodbye. In Indian culture, one is used to hearing people say that when they are taking your leave. It is a polite offering when exiting a room. No one buys into the rhetorical nature of the offer. She was just being a casual angel.

In the years since, the word ‘savarna’, or the four forward classes of people, has popped up several times on my social media timeline. Initially, it amused me, as I only associated sajna with savarna. Sajnasavarna is the kotha’s only jaat. I guess for me it still means checking the sajna’s entitlement before getting ready for him. Savarna has become an irrefutable part of our daily online discourse. It makes us check on our own complacency.

What works for me in a democratic anglophone society will not serve me well in the cow belt, extending to all regions lately. For long I have grazed pastures in disguise as a Gaekwad, ‘gae’ for cow and ‘kwad’ from door: cow door. Although, it is still the best bet. To belong to the Yadava clan helps you gain entry into the Kshatriya club. Second in the hierarchy after Brahmins. I have apparently not been doing too bad with my fake surname.

Also read: There’s no statue to Begum Mofida Ahmed in Jorhat. She was 1st Assamese Muslim woman MP

I am now acutely aware of my jaat, that I belong to a Scheduled Tribe from my mother’s side (Tamaichikar) and to the Muslim minority from my father’s side (Khan). Grandmother was from a banjaran background, possibly a Denotified Nomadic Tribe. Writer Anna Morcom, in her book Courtesans, Bar Girls & Dancing Boys, makes a mention of how, unlike for the Dalits, the DNT community never had a leader such as Ambedkar to force their interests on to the national consciousness. That makes me lowest in the order, along with my own personal identity belonging to the queer of caste. Three indelible strikes.

Merit alone has been my jaat so far. If people have been inferring my caste from my fake surname, they are making wrong calculations. As for my class and status, my English-speaking skills have been enough to clear my entry to any upper-class echelon in society.

In fact, I have to now elaborate that with my mother’s observation. She was once visiting me in Bombay. She sat on the sofa, holding her lunch plate. She looked me squarely in the eye and asked, Neeche baith jaaoon? May I sit on the floor? Stunned, I asked why, what about the dining table? Colour drained from her face. She described how she felt when I visited home for the holidays. I was six years old when I returned from Kurseong. She served me dinner and I nonchalantly asked, Mummy, where’s my fork and spoon? Her heart filled up. She told her neighbours, Phat phat angrezi bolta hai yeh toh. He speaks so fluently in English. She knew spoon as chammach, but had never required a fork for eating. Fok? she had asked me. Where should I sit? I had interrupted her. We did not have a table at home. We do now, in her flat in Calcutta, which I left in 2002, and in all the houses I have inhabited since then across the country, where she comes visiting every few years. She still prefers sitting on the floor to take her meals. English ne tujhe angrez banaa diya, she says. English has made you a foreigner.

My strong anglophone education has made me indifferent, to not educate myself and utilize the reservation quota that my underprivileged ST status accords me. The country is regressing to ancient times. Religion is shapeshifting into fanaticism. I may have to rely on magic and angels to survive in the future if I allow this to affect me. I have never hankered for caste politics, simply because in a kotha all are welcome, no one is judged by these ranks. There was a hierarchy among the older generation of deredarni tawaifs, who came from royal patronage and musical gharanas, and bednis, who came from trafficked girls—but that is about it. I am oversimplifying it for the express purpose that this is not an academic text. I am not an expert on the matter. What I do know from my experience is that caste does not spill over to who is allowed into the kotha. No kid is taught about caste. Here, money is the only jaat, paat and saath. Caste and company.

Tawaifs passed on their place in the hierarchy to their girl child, but it got diluted as new girls from various low castes entered the profession and mingled freely, sometimes bringing in the crowd, like my mother did, which freed her from the constraints of being marked as an outsider and made the deredarnis and bednis loosen their stranglehold on the profession and befriend her, often enjoying the fruits of her labour and blessing her for infusing vitality into their jaded business. Of course, they secretly envied her, but can they deny that she helped them survive in a trade where their class-conscious status was limiting their reach? Once they knew her, she did not face discrimination of any sort.

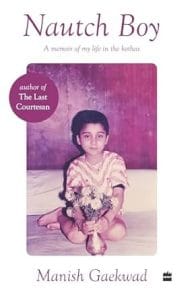

This excerpt from Manish Gaekwad’s ‘Nautch Boy’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Manish Gaekwad’s ‘Nautch Boy’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.