The constant news and dispatches from India about the Company’s bloody skirmishes with Mysore and its ferocious and tyrannical ruler left a deep imprint on the psyche of the average British citizen. While there was applause and rejoicing at his total and complete annihilation at the fall of Srirangapatna in 1799, there was also increased curiosity and a kind of oriental exoticism associated with the man, described as the Tiger of Mysore. As new revelations of his letters, his dream registers, exquisite jewellery and ornaments, costumes, throne and so on became visible to the common public of Britain, the interest and curiosity further peaked. Rapid translations from Persian and other languages ensued of the letters, manuscripts, recorded minutes and secret correspondences, and other memorabilia found in his possession. The British were desperate to get a peep into the mind of the man whom they so deeply feared and hated. A lot of what they found was new discovery; a lot of what they produced also ensured a confirmation bias.

In popular art, scenes from his life, be it the surrender of his sons as hostages to Lord Cornwallis, the final storming of the Srirangapatna fort, his last attack and his body being discovered by Sir David Baird and others became inspirations for wall paintings on displays.

By the end of the eighteenth and the start of the nineteenth centuries, panoramas were a popular form of entertainment in England with artists vying with one another to depict the truer to life and gigantic spectacles for a discerning audience.

An American artist, Mather Brown, who was living in England, wrote to the East India Company on 8 August 1792 expressing his desire to represent on canvas the episode of Tipu’s defeat in the Third Anglo–Mysore War and more so of the surrender of his sons as hostages. The Delivery of the Definitive Treaty by the Hostage Princes to Lord Cornwallis was the art that was then created by Brown. A version of this, of 44.5×52 cm dimensions, is seen at the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle. Cornwallis is seen looking down affectionately at the two boys, the younger of whom seems quite peppy and pulling his brother’s hand (perhaps being unaware of what was happening), while the elder one looks a bit distraught.

There is shock and gloom alike on the faces of Tipu’s party, while the British entourage behind Cornwallis sport a smug, victorious look. The work was exhibited at the Morland Gallery in November 1792, with a pamphlet narrating the details. Brown made several versions of this historical event, with Cornwallis being shown more affectionately, looking down and holding the hands of the boys. Sean Willock argues that ‘Brown showed the cross-cultural recognition of Cornwallis’s paternity to have particular implications for imperialism . . . the supposedly benign treatment of the hostages is thereby registered as a spectacle of British benevolence, while the paternal relationship of Cornwallis to his captives is thought of as precursory to the political ties necessary for the maintenance of empire’. He was seen leading them to a British (read civilized) way of life and etiquette, it seemed to convey, and thereby he was actually doing the boys a great favour. The boys leave behind billows of smoke, crestfallen but savage-looking natives, elephants and clasping the hands of their benefactor, they move on to a better life.

The work of Francesco Bartolozzi, titled The Departure of the Sons of Tippoo from the Zenana, that came thereafter in around 1794, had an imaginary scene as compared to Brown’s. It depicts the scene in the zenana of Tipu where the several female members of the family are seen giving the boys a tearful farewell. Menfolk and two howdah-bearing elephants wait in the vicinity to usher the boys away. Obviously neither the men (nor of course the British) were given access to the most private of chambers, namely the zenana. Numerous known and anonymous artists began depicting the scene in their own imagination, showing how potent the symbolism and the myth surrounding Tipu Sultan and the significance of his annihilation was for the empire—all this, even when he was still alive and fighting the British. The return of the sons, too, is depicted in a few paintings around and after 1796.

After the death of the Sultan, Sir Robert Ker Porter (1777–1842) was among the earliest artists who invited subscriptions for his new artwork on the fall of Srirangapatna, which began appearing in newspapers from early October 1799 itself—barely six months after the storming back in Mysore. Although he had never visited India, Porter made this painting in a short span of barely six weeks, based entirely on inputs from the Company and its correspondences.

His famous painting—The Storming of Seringapatam—was first exhibited to the public on 29 March 1800 at the Lyceum and was a large 120-feet long and 21-feet high canvas painting, covering in all 2550 square feet of canvas.27 Several prominent British officers involved in the ambush were featured in it. It froze that moment of time when the fort was breached at two places and the Company officers were advancing inside, with fire, smoke, canons, guns seen all around, with the gopuram of presumably the Ranganathaswamy temple looming over all the anarchy from a distance. The exhibition was widely attended with people paying an admission fee of a shilling.

Those seeking more historical background could pay an additional two shillings to pick up an elaborate booklet titled Narrative Sketches of the Conquest of Mysore, running into nearly 120 pages, to aid the art, ‘on a scale and magnitude hitherto unattempted [sic] in this country.’28 The booklet is said to have become so popular that it was reprinted four times in two editions between 1800 and 1804 with thousands of copies being picked. It had graphic details of Tipu’s atrocities against the British prisoners and was possibly aimed into directing public opinion in Britain on the appropriateness of the war and the justified murder of a tyrant. The sheer size, spectacle and storytelling that came along through this gigantic art made the spectator feel as though they were one with the officers on that fateful day in May at Srirangapatna. Porter’s work greatly enhanced the military prestige of the Company as a harbinger of justice and national pride that ‘patriotically advanced and enhanced the government’s full-blown vision of empire as a historical spectacle of glory in which all amongst the British populace could participate.

The booklet ends with a triumphant and self-congratulatory note:

Thus have the wisdom and energy of British councils, and the steady bravery of British soldiers, united to overthrow one of the most powerful tyrants of the east; to accomplish as complete and as just a revolution, as can be found on the records of history; and to produce such an increase of revenue, resource, commercial advantage, and military strength to the British establishment in India, as must for years to come ensure a prosperous and happy tranquility, not only to the Company’s possessions, but to the native principalities, and to millions of inhabitants on the fertile plains of Hindostan.

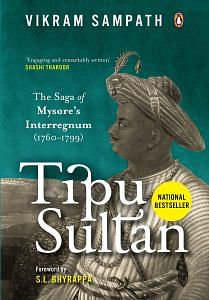

This excerpt from Vikram Sampath’s ‘Tipu Sultan: The Saga of Mysore’s Interregnum (1760–1799)’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Vikram Sampath’s ‘Tipu Sultan: The Saga of Mysore’s Interregnum (1760–1799)’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.