It is close to midnight. Daisy is sleepy. And hungry. But she will not get any food until she shakes off her slumber and gives that perfect shot that the director wants, and her mother is out to ensure it happens.

Daisy is too scared to say that she must eat before she can perform. For that would elicit a stinging slap on her face from her mother. In front of the entire unit. The little girl calls upon her reservoir of strength to finally deliver the shot that is cleared.

The director is thrilled; mother nods. And Daisy slumps to sleep in the car she’s hurriedly shoved into. Sheer fatigue overtakes hunger. Her mother counts the cash as the car whizzes though the dead of the night. On the sets the bright lights are finally switched off. It’s dark. Everywhere. Deepest in five-year-old Daisy’s life.

Tucked away in a cosy apartment in Mumbai’s Versova neighbourhood is where the Bollywood legend Daisy Irani now lives. The beloved child actor who once reigned over Bollywood in the 1950s and 1960s stays here with her daughter and her family.

Now seventy-five years old, Daisy struggles to recall names of contemporary actors she admires or the most recent show she has seen on television. But her memories of the studios and film sets from her acting days are too vivid even today: of the producers who tried to strike a sexual deal in exchange for a role, of the directors who took advantage of her vulnerable age, of her mother who was complicit in her exploitation (both sexual and monetary), of the man who raped her at the age of six during an out-of-town film shoot. Despite her outwardly jovial demeanour, the sorrows that sweep over her are too frequent. ‘Every day,’ she says.

Young actors, especially from the yesteryears, were usually victims of poor awareness and lax laws. Many were, and still are, compelled to work in the film industry because of dire financial circumstances and were often the sole breadwinners in their families. Daisy didn’t have even that consolation. She hailed from a well-to-do Zoroastrian family with four siblings: older sister Menaka Khan, the mother of well-known directors Farah Khan and Sajid Khan; younger sister Honey Irani, mother of actor-director-singer Farhan Akhtar and acclaimed director and scriptwriter Zoya Akhtar; and two elder brothers, Sarosh and Bunny. Her father was a well-educated man who owned an Irani restaurant, Meherwan, in front of Mumbai’s bustling Grant Road Station. His children certainly did not need to support their family.

Yet, Daisy was just three when her mother, Perin Irani, decided to send her to film sets rather than to school. ‘My mother came from a poor family with very little education. She constantly fought with both my father and her mother-in-law,’ says Daisy. She thinks of her mother as her ‘nemesis’.

‘For some odd reason she decided that she would make me the vehicle of her pride; something like, see what I can make of her.’ It wasn’t just Daisy that Perin tried pushing into the film industry. Her younger sister, Honey, too became a puppet in the hands of a mother possessed by her own ambitions. Then, their third sister, Menaka, was pulled out of school and pushed into acting too. But Menaka would have none of it and showed no interest in becoming a film star.

‘Though she couldn’t go back to school, Menaka refused to go to the sets too. As soon as she turned eighteen, she married filmmaker Kamran Khan who was fortyeight at that time,’ says Daisy. Her brother too suffered his share, albeit differently, something Daisy realised only recently.

‘Just last year my elder brother confided how he always felt uncared for and intimidated by our mother. It’s true when they say that if one bad woman comes into the family, she can destroy the entire lot. I know even Honey went through a lot of trauma, but unlike me she doesn’t talk about it.’

Also read: How Mumbai grew—and became crowded

Despite all the hardships, by the end of her career as a child actor, had acted in over 300 movies. A natural talent with no formal training – not that there were many acting schools back then – she was quick on the uptake, delivering her lines with the ease and confidence of a veteran.

Except for her debut, Bandish (1955), most of her later work was often cleared on the first take, and she commanded top credit billing through the 1950s and well into the 1960s – some roles were even written and rewritten specially for her. From Ek Hi Rasta (1956) to Naya Daur (1957) to Hum Panchhi Ek Daal Ke (1957), Aankhen (1968) and Kati Patang (1970), Daisy rapidly became the most successful and well-known child actor of that era.

But personally, she was a wreck. On one hand was the child star with the short, curly locks, the impish smile and the big, expressive eyes that lit up the black-and-white screens of Bollywood; on the other was Daisy, the little girl, whose childhood was ravaged – she calls it a ‘never-ending black comedy’ – and irretrievably lost. She admits that she does not remember much about the shots themselves, just that she had to do as she was told, whether she liked it or not. Refusal meant severe beatings from her mother and no food.

‘Simple indulgences like eating some tamarind or raw mangoes were forbidden because they could make me ill and that would affect the shooting dates and schedules. I remember being very busy; I would be shooting day and night. I would catch up on my sleep in the car on the way to the sets – thank God those days we had spacious cars. But it was not an easy life, for sure.’

Also, Daisy never saw the considerable money she earned. ‘My mother took it all, and one couldn’t ask her about it either. I also won so many awards as a child actor. But she sold all of them!’ It was only much later, as a teenager, that Daisy was inspired by her co-actors Zeenat Aman and Parveen Babi and plucked up the courage to demand her earnings from her mother. It was almost too late, but it did help her in one unexpected way. ‘I at least started coming alone for the shoots and that itself was a big relief.’ Going unaccompanied by her mother was a changing point in her life.

Daisy was aware that there were other child actors, her peers, who were also being manipulated by their mothers in the same way. ‘There was Baby Naaz and then Sarika. Sarika’s mother was very weird. These mothers had no emotions or love for their daughters. They just used them. One thing about a lot of the child actors’ mothers was that they loved hanging around the sets; they were on quite a trip of their own.’

Inexplicably, Daisy’s father, the late Nosher Babban Irani, did not step in to stop this exploitation of his children. But Daisy does not hold this against him. ‘My father was a good man. He would be out of the house from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Maybe to escape my mother. He also took a lot of nonsense from her, but he never created scenes in front of us to keep the peace in the house for the five of us. But my mother was uncouth, shameless and dominating. My father died very early. My mother would go to the hospital when he was ill and ask him, “Where is all your money, whom are you leaving it all to?” By that time I had grown up, so I would order her out of the room. Years later, I also told her that I would tell the world about what she had done to us. But I don’t know whether it had any effect on her.’

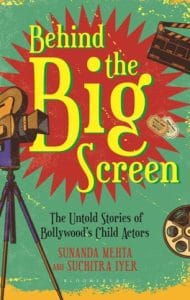

This excerpt from ‘Behind the Big Screen’ by Sunanda Mehta and Suchitra Iyer has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from ‘Behind the Big Screen’ by Sunanda Mehta and Suchitra Iyer has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.