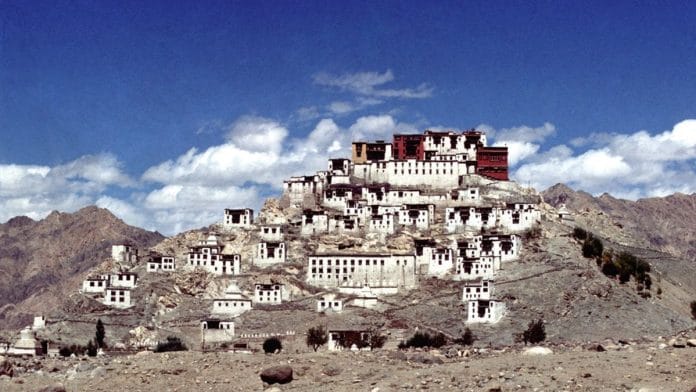

Located southeast of Leh, on a hill above the Thiksey village, the Thiksey Monastery is one of the largest monastic complexes in Ladakh, India. It is notable for the Buddhist murals, sculptures, and important manuscripts housed within its various structures, and is administered by the Gelugpa order.

Thiksey was established in the mid-fifteenth century by Pon Sherab Raspa, nephew of the monk Je Tsongkhapa, who founded the Gelugpa order. It was patronised by the ruler of Ladakh, Raspa Bumde, as well as by several rulers of the ruling Namgyal dynasty. Along with Likir, Phyang and Spituk, it is one of the several hilltop monasteries constructed in Ladakh from the fourteenth century onwards. During this period, the spread of Islam and declining patronage for Brahmin and Buddhist practices in Kashmir led to a decline in its cultural exchanges with Ladakh, with Tibet emerging as an important influence on the practice of Buddhism in the region instead.

This period was also one of significant political turmoil in the western Himalayas. Kashmir frequently came under foreign occupation, which brought the invaders into uneasy proximity to Ladakh. The Ladakhi rulers shared a discordant relationship with the Dalai Lamas of Lhasa. The monastic complexes built in Ladakh in this era functioned as both administrative and religious sites, and were heavily fortified, along the lines of the monasteries of Tibet.

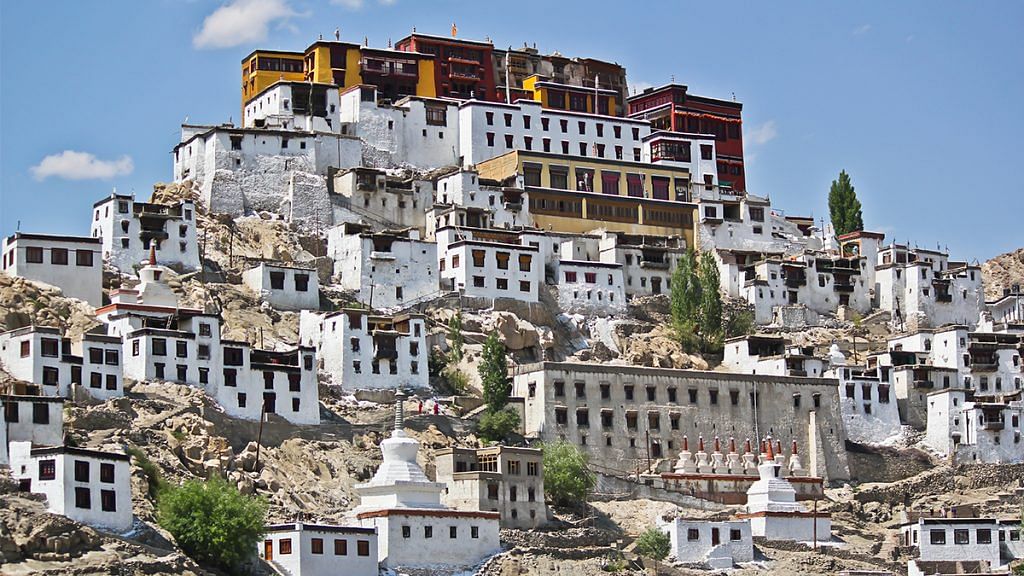

The Thiksey Monastery complex is bound by a large chagri, a perimeter wall, with a large gateway serving as its entrance. A path lined with white chortens, and mane, or prayer walls leads up the hill, and opens into the central courtyard, where public gatherings, including the annual Thiksey Gustor festival are hosted. In the middle of the courtyard is a raised seating area that is occupied by the head of the order — the Kushok — during functions, while the painted spaces on the sides of the courtyard are used to accommodate members of the general public.

Also read: How John Edward Sache photographed 19th-century India

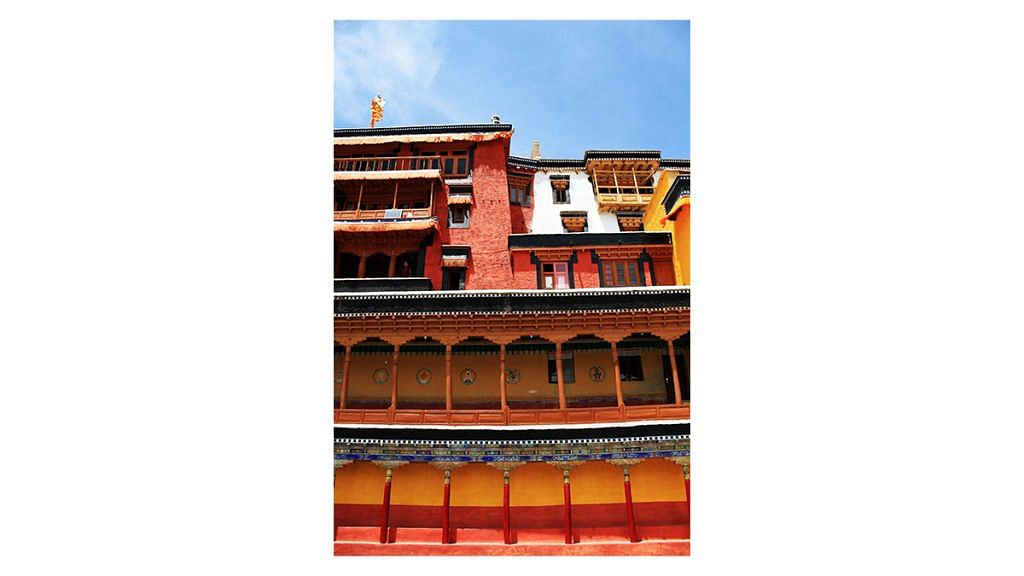

Like other Buddhist monasteries in the region, Thiksey is arranged in such a way that its oldest and most significant structures — the old Dukhang, the Gonkhang, and the quarters of the head monk — are found at the very top, close to the central courtyard. The residential quarters of other monks are located below the central courtyard, arranged near one another on the hill’s slope, often sharing walls or separated by narrow alleyways for pedestrians. These smaller buildings are interspersed with other larger structures, including temples and prayer halls. As of 2018, the monastery had living spaces for eighty monks, in addition to a nunnery. At the base of the hill is a complex that was built in 2010 to host the photang, the annual meeting of senior lamas.

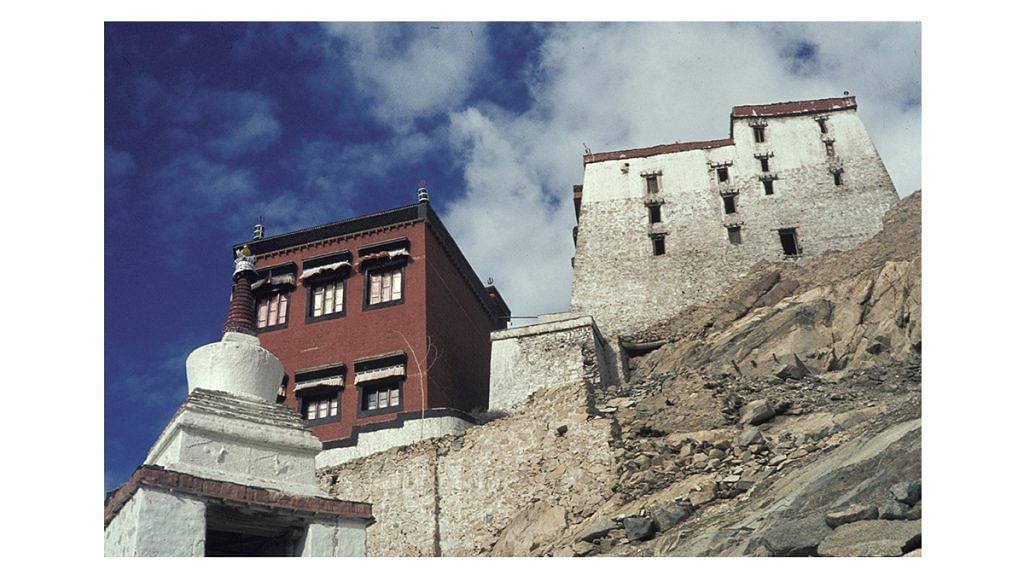

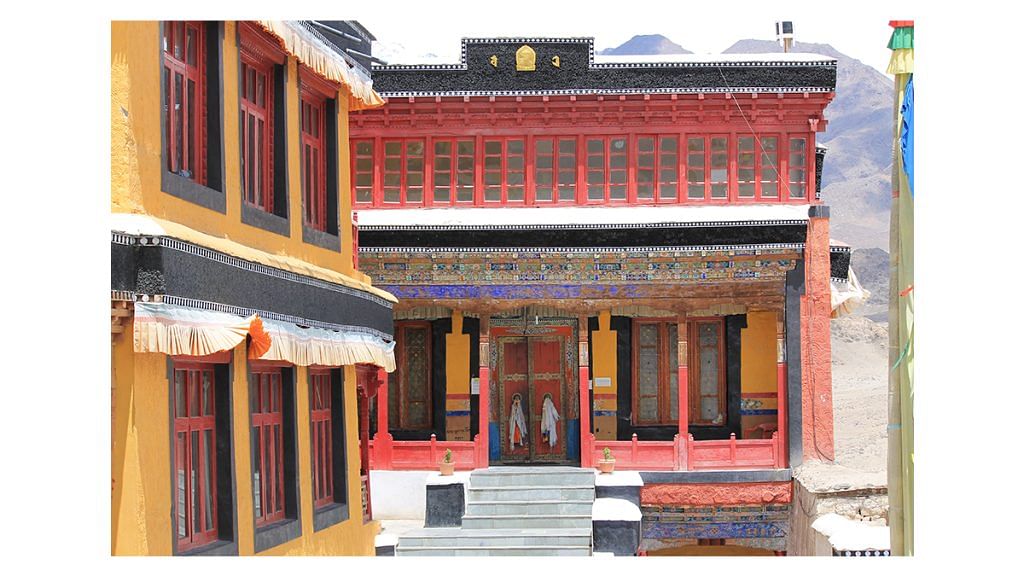

The Dukhang — painted ochre and orange — can be accessed from the courtyard by a flight of stairs. Its external facade is characterised by wooden loggias, while its interiors are distinguished by several carved wooden pillars that create a gallery-like space. The walls of the Dukhang are painted with murals, and thangkas hang from the edges of the ceiling next to one another, lining the upper portion of the structure. Long wooden benches line the walls and are reserved for monks. Two cone-like painted wooden pedestals that hold two large Shakyamuni sculptures. The Dukhang has a small antechamber, known as the tsangkhang, with painted walls, and housing sculptures of Padmasambhava, Maitreya, and Shakyamuni.

The Gonkhang, with a red exterior, is a three storey located next to the Dukhang and is believed to be amongst the oldest buildings in the complex. It houses fierce protector deities.

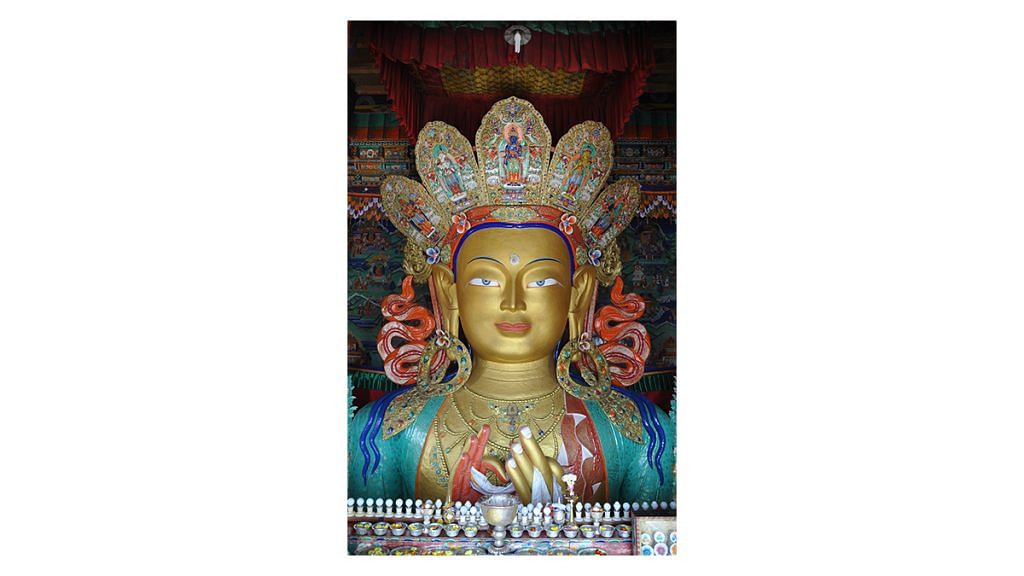

Other notable structures in the complex are the Tara Lhakhang, dedicated to Tara, the Lhamo Khang, dedicated to Palden Lhamo, and the Chamba Lhakhang. The Lhamo Khang houses a number of important manuscripts, as well as the deity, and access to it is restricted. The Chamba Lhakhang is a three-storey rectangular building. It was built in 1979–80 and houses an imposing sculpture of Maitreya, also known as Chamba, created by the Ladakhi artist Nawang Tsering.

Despite their varying functions, the structures at Thiksey have a visually unified exterior. Whilst the more important structures at the top of the hill are painted in shades of yellow or red, the walls of the other buildings are painted white, with thick black lines demarcating the windows and roofs. The buildings in the complex are made primarily of stone, mud bricks, clay and timber. Because of its colour scheme and layout, the monastery is often likened to the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

The use of cement and other modern materials has been limited to the maintenance and repair work carried out over the last few decades. As of writing, the renovations carried out within the monastery include the construction of a new kitchen and dining hall for monks, the demolition of an old structure in the central courtyard to make space for a new temple, and the paving of the central courtyard with granite.

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which lists the Thiksey Monastery as a Monument of National Importance, is responsible for its conservation. However, the ASI’s approach to conservation in Ladakh has faced criticism from experts as well as the monks residing in monasteries such as Thiksey, who have expressed concern regarding the poor quality of the repair work undertaken by the agency.

This article is taken from the MAP Academy‘s Encyclopedia of Art with permission.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through its freely available digital offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—it encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.