In his rather salacious memoir, the journalist doesn’t offer a nuanced perspective about the personalities and events that shaped India.

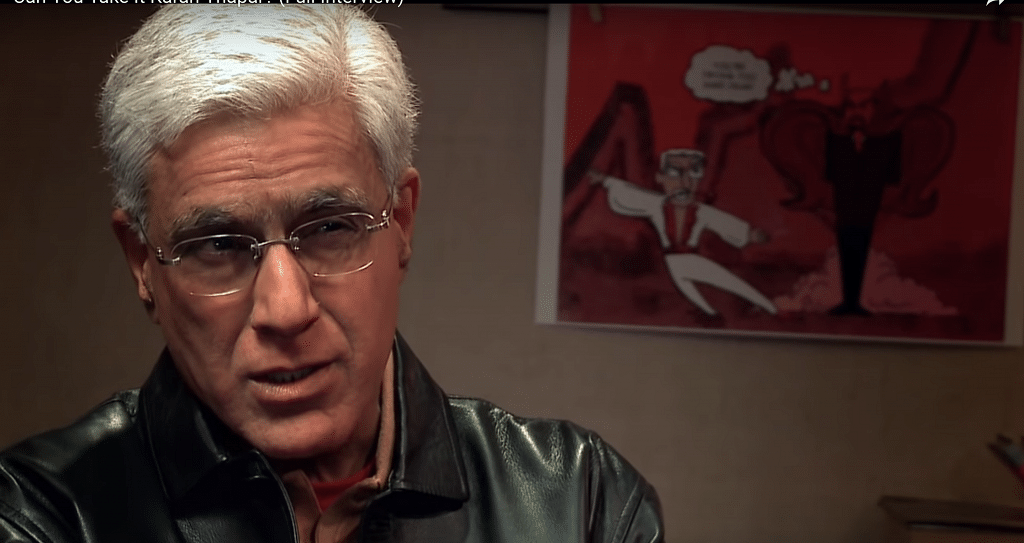

Veteran journalist Karan Thapar’s memoir, Devil’s Advocate: The Untold Story, is all anyone has talked about lately, courtesy a snippet where he mentions his lost relationship with Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In the excerpt, Thapar says despite repeated attempts and assurances, from none less than the BJP president Amit Shah, he lost access to Modi after a 2007 interview. Consequently, other BJP leaders too started declining his request for interviews.

It’s perhaps this particular chapter that forced Thapar to tell his story, in a rather sensational memoir.

Privilege, access and entitlement are words that probably sum up Thapar’s life for many. From the very beginning, he found himself at very centre of power in India — Lutyens’ Delhi. He was, after all, born to former Indian Army chief Pran Nath Thapar and is related to prominent historian Romila Thapar, writer Nayantara Sahgal and conservationist Valmik Thapar.

In what can only be called salacious, Thapar recounts his close friendship with Congress leader Sanjay Gandhi, one of the most prominent political figures during the Emergency. But the only detail Thapar offers about Gandhi is that he used to visit his house regularly.

Same goes for other important leaders who find mention in the memoir, including four former prime ministers – P.V. Narsimha Rao, V.P. Singh, Chandrasekhar and Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Thapar recounts in great detail how he managed to meet each of them, some while they were still in office. But Thapar has little insight to offer about any of them.

He also doubts the accuracy of his memory, inexcusably, at many points in the book. He could have maintained notes, or a diary, and if not either, devoted time for research before making claims. He fails on all three counts.

As things stand, the memoir reads more like how things could have been, rather than what they are. It’s a missed opportunity to offer a nuanced perspective about the personalities and events that shaped the social, moral and democratic fabric of India. Instead, it seems to be a vainglorious exercise in self-aggrandisation.

The only interesting tidbit Thapar has to offer is Modi’s take about the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). In 2002, Modi, then a BJP office bearer, helped Thapar understand the RSS while he was slated to interview the RSS Sarsanghchalak. Today, it’s difficult to imagine that Modi called his parent organisation ‘mediocre’.

Thapar’s memoir, however, comes across as facile. It reads as if he was writing a tweet and his argument suffered space constraints. A little self-reflection and introspection on the part of the journalist would have gone a long way in making this memoir a worthwhile read. May be, he could have done justice to it by naming it Devil’s Advocate: The Told Story.