There is nothing new in saying that Bihar is the poorest state in India. It has been so for generations. That doesn’t mean, however, that it hasn’t changed—and changed mostly for the better, as you read the writings on the wall.

The change isn’t confined to Patna getting its first star-rated—in fact, a five-star—hotel from the Taj Group. Linked to the hotel is also the City Centre Mall. The first such of any size in Patna, hosting many brands. The Crossword chain has a book shop here and a shelf lists the top 30 best-sellers. Check these out—Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me is at the top, of course. On the same wall, you find Peter Thiel’s Zero to One, two top-sellers from Morgan Housel, The Psychology of Money and The Art of Spending Money, Ikigai, the Japanese Secret to a Long and a Happy Life, and some more.

The salesperson tells me they sell two to three of each per day, considerably more over the weekends. We are aware that nothing changes the fact that Bihar’s per capita GSDP is still within $900, or less than one-third of the national average, as it always was. It is just that two decades under Nitish Kumar have created a new elite in its cities, especially Patna. There is, from the evidence of this ‘wall,’ a curiosity, at least among a significant number, for money: both for its psychology and about how to spend it.

Over generations, Bihar’s bane has been its utter lack of urbanisation. A bit sad for a state that boasted the Subcontinent’s greatest cities and empires more than two millennia ago. Even today, 88 percent of its people live in its villages. But now, even Bihar is urbanising. Or let’s say, rurbanising. In the most elite private residential areas of Patna, say Patliputra Colony, roads are bumpy, cratered and raised with multiple layers of tar poured for a quick fix year after year.

And you can see why they are still streets to fit some fourth-world definition: because no drains have been built alongside them. All the rainwater collects, eating up the surface. As does much garbage. If Patna is growing and gentrifying in so messy a manner, you can imagine the rest of the state. But urbanising it is, if even more chaotically. In village after village, the one activity you see is construction. Bihar is in the throes of an almighty construction boom.

We drive through Goh in the once-Maoist heartland of Aurangabad, just about 120km from Patna, not far from the Son river. New concrete dwellings, mostly four to five stories, are rising on both sides of the narrow street on top of what used to be barely pucca, modest homes. All have cantilevered balconies, from which curious people look down as a political procession passes by, and ornate terraces.

Where is the money coming from? It’s a combination of remittances, giveaways under PM Awas Yojana, and indeed some rising local incomes, especially among women with self-help groups. If you had been to Bihar a decade back, you would not recognise this countryside. It’s like another country.

It is still poor, crowded, and more smog-laden than even Delhi, for which there is a reason we will soon explain. But, for the first time, lots of people have some surpluses large enough to build new, relatively fancy homes. I looked at the windows on the many floors instinctively, searching for that tell-tale image of new prosperity—an air conditioner. That’s one thing I didn’t find over long drives. It tells us there is money to build these houses, luxuries still must wait.

Also Read: Writings on the Haryana Wall still have Modi first, just the first among equals

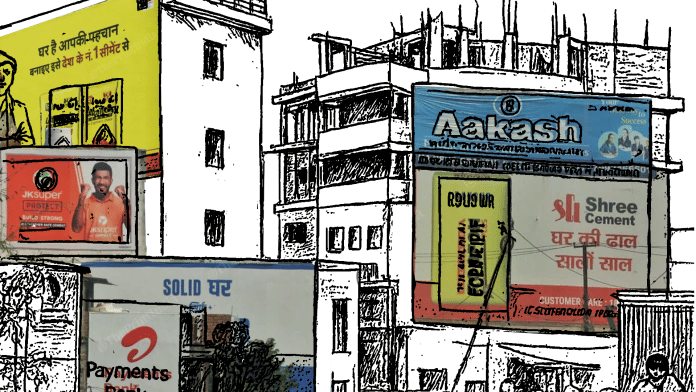

Keep looking up and reading the writings on the wall. In my previous travels beginning 2005, we started with no walls, only thatched huts and some signboards on trees, to English-medium education (2005), branded underwear (2010), and UPSC coaching and branded babies’ diapers (2014-15). Education is a permanent feature across India now. In Bihar, however, the skyline is owned by construction materials. Anushka Sharma and Virat Kohli sell one brand of sarias (iron rods) – “Flexi-Strong matlab hamesha ke liye strong”—and to build a home with these, there is a cement brand endorsed by Jasprit Bumrah, fists raised in celebration with the slogan “Build Strong”.

Every cement, saria and paint brand in the country is being sold on the walls of Bihar after two decades under Nitish Kumar. There is more. Airtel Pay appears often enough to remind you that this is a remittance economy. If we saw Bihar’s progression from basic, school-level private education to branded underwear and UPSC coaching, we now have a boom in dentistry. Even in the really small towns, qualified orthodontists and specialists have set up well-equipped clinics offering root canal surgery, implants, full mouth reconstruction and cosmetic work.

My favourites: Smile You Choose, and ‘32 TEETH HOSPITAL” in Daudpur offering dental implant cosmetic dentistry and laser endo-dental surgery. It’s run by doctors Pranav and Alka Singh, dentistry graduates from Azamgarh and Lucknow, respectively. Once again, to remind you, this is in the heart of the once Naxal-controlled zone where ‘revolutionaries’ walked around freely with weapons, even posed with them for news photographers with pride.

The Aurangabad zone and its armed ‘fighters’ built the legend of late Krishna Murari Kishan, the doyen of news photographers in Bihar and who we grew in awe of as young reporters. The change now is so stark that you can understand how just a return of law and order and reasonably decent governance are the deadliest slayers of these furious revolutions in desperately hopeless zones. A Tanishq jewellery showroom in Aurangabad is as good a metaphor for a failed revolution as you can find anywhere. As is the appearance of pet shops and clinics. The standout brand name for me, in Patna, is Bark n’ Brush with an attached ‘Dog Hospital’. There is, of course, a dental hospital on top of this. I get my story in one picture.

No surprise, then, that the strongest pitch from the NDA, even more effective than the giveaways it is spraying freely, is that Nitish Kumar has restored law and order. Do you really want a return of “Jungle Raj”? It is the one time Nitish Kumar lifts his head from the three printed sheets of paper he reads from at his modestly attended public rally in Masaurhi (Reserved) constituency about 40km from Patna. It is the only time he is able to rouse a crowd bored as it should be in a state known for brilliant orators, not mere readers. Hundreds of arms go up as people say the equivalent of no, never.

Nitish is now a caricature of himself. His health has faded and his mind has some good moments and some tricky ones. Nobody’s allowed to meet him, and at a point in politics when he should have been riding high, he isn’t trusted with anything more than a purely written, short speech. The fact is, the BJP has no choice. It has no Bihar leader who could collect even 10,000 people.

I have said for years that Bihar’s politics is like a bunch of bogeys in different colours on a railway station with no engine in sight. Then, at some point, the engine arrives, and it is called Nitish Kumar. That’s how he’s been in power in partnership with the BJP, Lalu-Congress, or even by himself for these 20 years, barring the few months when he moved out tactically, appointing Jitan Ram Manjhi (now an NDA partner) as his Dalit place-holder. He’s the indispensable engine the BJP train still needs desperately. The dominant party may be the BJP, but the vote it seeks is for Nitish, even more than for Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

If construction is the engine driving Bihar’s economy now, its downside can be witnessed along all of its rivers, especially the many and mostly unruly tributaries of the Ganga. Bihar has many rivers and has historically endured a flood-drought cycle. Floods bring enormous sands from the brittle Nepal foothills and as the rivers dry, local contractors, politicians, thugs, mafiosi all descend on the dry bounty of sand. The state highways along the rivers have endless convoys of open trucks carrying sand, a lot of it flying in the air, making large parts of rural Bihar among the most polluted in the country. This is despite having zero industry.

Officers in districts say there is some pretence of an auction or bidding, but it is just that, a pretence. The rest, almost 99 percent, is simply stolen by the sand mafia even Nitish’s law-and-order machinery has chosen not to mess with. One frustrated officer, not wishing to be identified for obvious reasons, tells us: “Such is the power of these mafia, and so much money they produce, that they can intimidate or buy anybody.” They are “taking sand to Kolkata, Delhi, even the South, because the entire country is in a construction boom and short of sand”. In the process, Bihar’s air is ruined, revenue lost and river beds suffering a crippling depredation. Try driving on one of these ‘sand highways’ at night time. You wouldn’t dare again.

If law and order is the biggest Nitish/NDA asset, its liability is the failure to create jobs. Bihar has seen national and state highways, even rural roads built at warp speed. But no industry, although on paper, it seems to have gone ahead of agriculture as a contributor to GSDP. It is just that we are talking of a very low base.

Joblessness is a millstone around the NDA’s neck, and all challengers see an opportunity here. Unemployment has two consequences. One, the usual rural distress, but the second is out-migration to other states for low-paying, mostly labour-wage jobs. The latest estimates tell us that 7.2 percent of Bihar’s population has migrated to work elsewhere. That would mean nearly a crore of men, seven to eight lakh of them in just the buzzing low-tech manufacturing hub of Surat in Gujarat. About 52 percent of Bihar’s families receive remittances. That the average size per year is just Rs 35,000 indicates how low-paying these jobs are. This results in separated families, with wives bringing up the children all by themselves.

One contender this time, the most visible “outsider”, has made this out-migration, or what is described here more effectively as ‘palayan’ (exodus), his central talking point. Prashant Kishor and his Jan Suraaj Party are promising to reverse it. He doesn’t hold public meetings. He only does endless roadshows. We travelled in his car for hours and every few kilometres, he’d stop in a village with the same message: jobs, reversal of ‘palayan’. “Modi ji says he’s giving you free data so young people can make reels and earn a living,” he says, mockingly. “We only say to Modi ji, I don’t want your data. Just send me back my beta (son).” He thinks the migrant labourers are his best campaigners and they will convince their families to vote for him.

Contrary to the ‘hawa’ that built up towards the end of the campaign, there is no sign that he has either abandoned his ambition in favour of the BJP/NDA or that he’s secretly helping them. His typical five minutes on the stump mostly target the BJP/NDA. Does an outsider like him with no ideology have a chance in a state as politicised and caste-polarised as Bihar? He says he does. Each day, he says, his postings on social media—mostly YouTube and Facebook—have 30 crore views, with enormous engagement. That fact anybody can check. Will that translate into votes? His answer is the now-famous ‘ya arsh par, ya farsh par’ (I will be either flying high in the sky, or laid flat on the floor). Either way, he says, he’s here to stay in Bihar politics.

The desperation for jobs is compounded by another fact not peculiar to Bihar, but more pronounced here. Literacy has boomed to over 75 percent now, school enrolment is almost universal, but dropout rate Class 10 onwards is very high. That leaves too many unemployable, but literate people. Many others who get past school are looking for jobs in armed forces, central armed police and state police forces. A most prominent writing on the walls of rural Bihar, therefore, is academies to give physical training for these prospective recruits. Many are run by veterans. R.P.A. (Rakesh Physical Academy) Sports is one.

Every morning, hundreds of boys—and many girls—arrive dutifully to be put through their paces to pass “physicals”. In Masaurhi, as elsewhere, I find something I hadn’t spotted before. Concrete cricket pitches with nets. I had first seen these almost as a standard feature in Pakistani Punjab villages two decades ago. Concrete is an option, given how difficult it is to maintain a turf.

And who knows, it might build a culture of fast bowling, as it did in the good days of Pakistan cricket. But, like our Punjab, Bihar is seeing the rise of a youth-destroying addiction. In village after village, people talk of the rising consumption of ‘ujla’, which is almost a literal translation for the ‘chitta’ (white), a kind of crude heroin cocktail popular in Punjab. Many, like O.P. Sharma, a contractor in Masaurhi, also gather the courage to blame it on overzealous implementation of prohibition.

If you go to the earliest writings on the wall from Bihar from 2003, you will see how we talk of the entire state plunging into darkness with sunset as there was almost no electricity, especially in the villages. That picture has now transformed dramatically and the story can be read on the walls as you drive past any village at night time. On the walls, outside each home, you find the tell-tale green flicker of the light on an electricity meter. Whoever wins power in the elections, Bihar has at least had a total electric power revolution under Nitish.

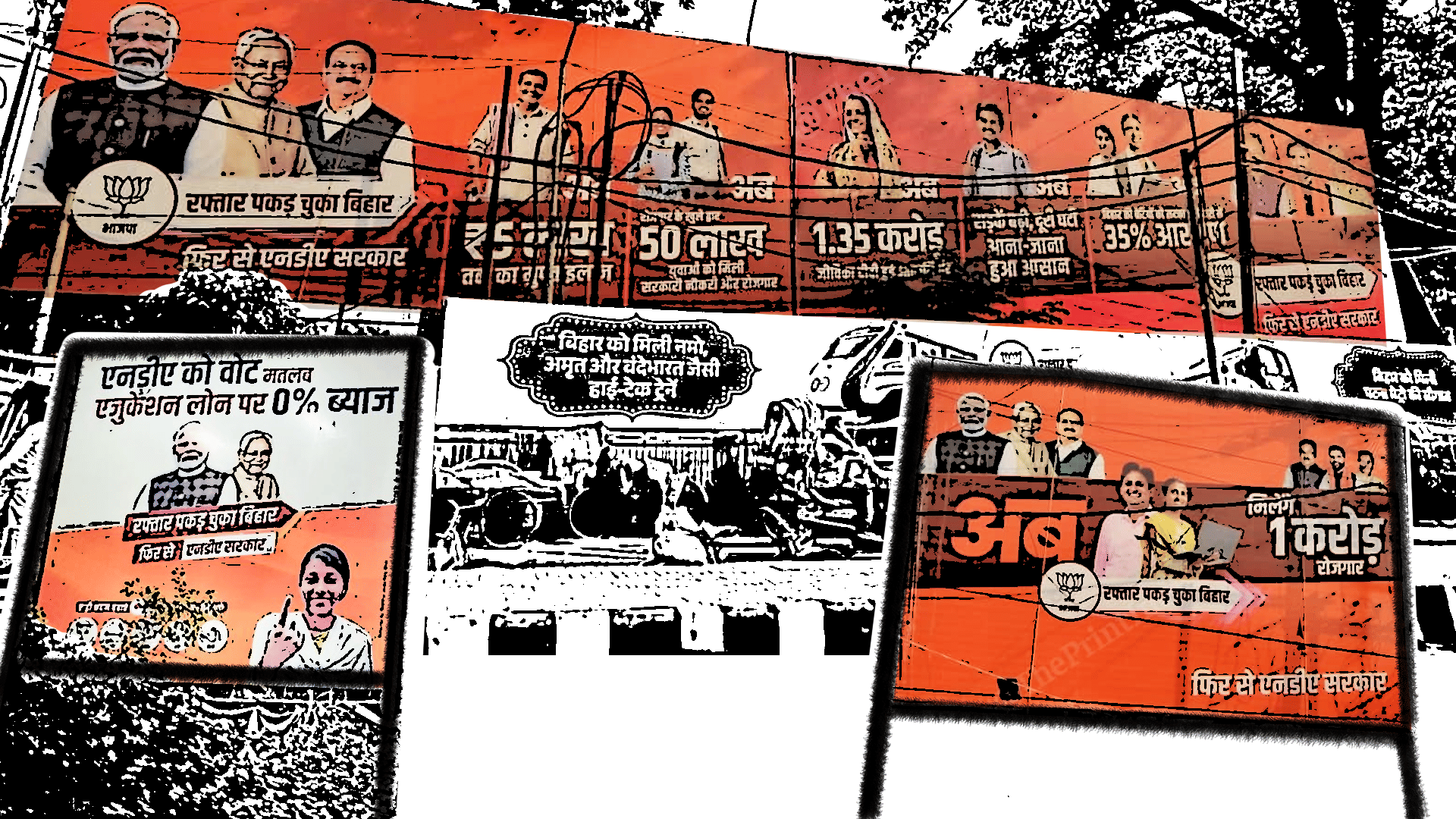

And yet, for some reason, the BJP/NDA combine isn’t sure of winning based on this record. As usual, their hoardings and posters outnumber the competition 50 to one, if not by even more. And much of their messaging is about the giveaways. These hoardings, the Rs 10,000 one-time payout to women, free electricity and education loans at zero interest also form an endless wall in front of the BJP state headquarters in Patna. Bihar is where we first noticed the rise of the aspirational voter. All of these years, both Modi and Nitish mocked freebies. This has changed dramatically. They’ve obviously concluded that to win again, to defy two decades of anti-incumbency, they now needed to hit the transactional button on the heart of the once aspirational voter. This is a writing on the Bihar wall, too. It just isn’t the most virtuous one.

And here’s a story you will find mostly in Bihar in the Hindi heartland. Despite all messaging for communal polarisation, ‘ghuspethiya’ (infiltrator) talk, Bihar doesn’t seem moved. It is difficult to find any communal impulses. And social conservatism? At one level you can forget it in Bihar. Most women in the villages don’t even bother covering their heads, look you straight in the eye, and talk.

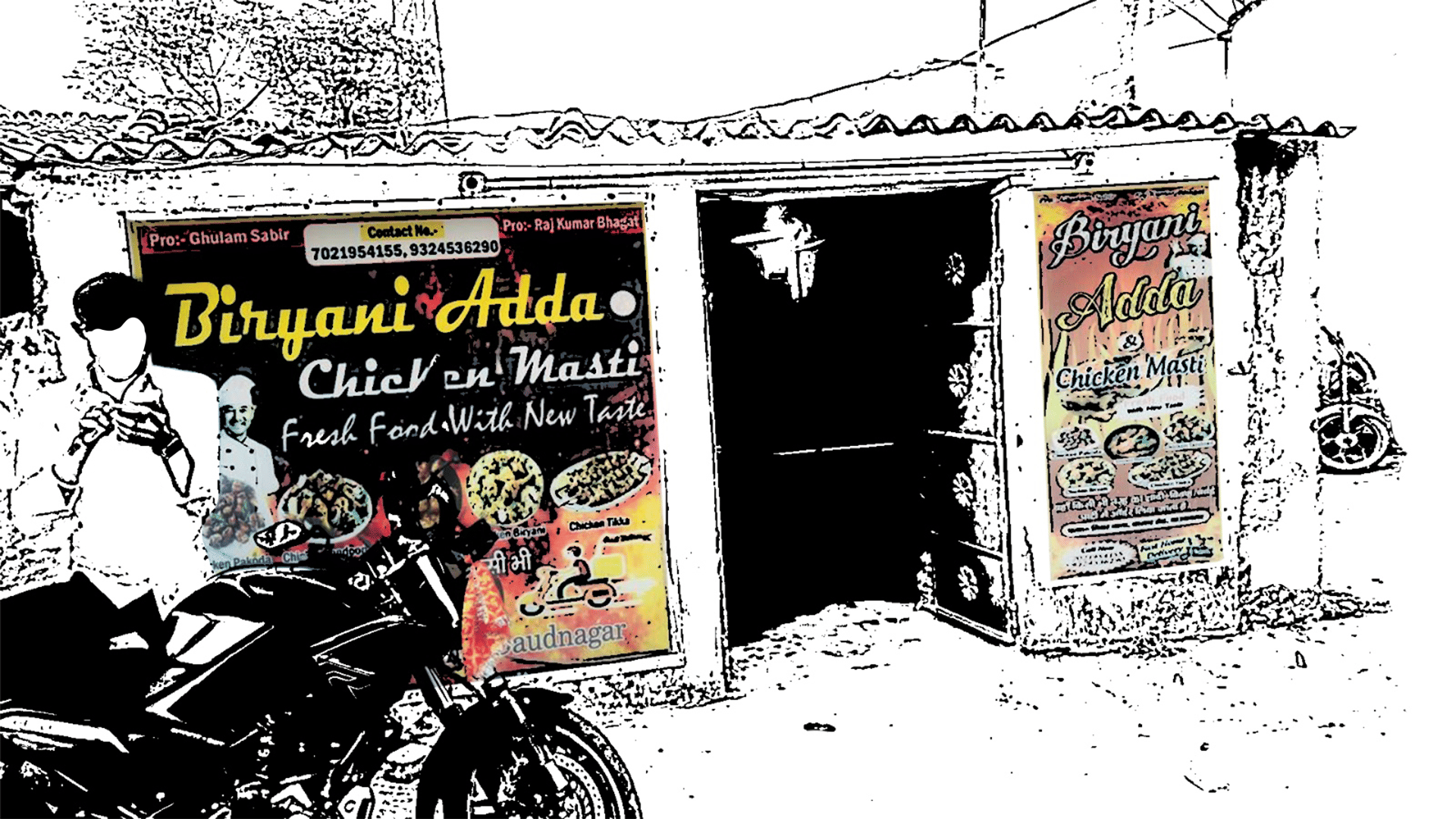

Come to Daudnagar. Along the main road cutting through the little, quintessentially crowded Bihar town, you will find a modest biryani hangout under asbestos sheets. Biryani Adda-Chicken Masti offers ‘fresh food with new taste’ and the names of the co-owners are on its signboard: Ghulam Sabir and Raj Kumar Bhagat. Here is another something that sets Bihar apart.

Also Read: Education, aspiration & 3 de-hyphenations: A changing Kashmir votes and vents