The most important decision-maker for the future of the climate isn’t Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, Chinese President Xi Jinping, U.S. Senator Joe Manchin or Tesla Inc. Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk — it’s Federal Reserve Chair Jerome H. Powell.

You might not think that interest rates were as crucial as carbon pricing, the price of oil, the cost of polysilicon for solar panels, or whether you can buy an electric SUV for less than a gasoline-powered equivalent.

In fact, they’re a central consideration, because of a key difference between the way fossil fuel and zero-carbon power is paid for.

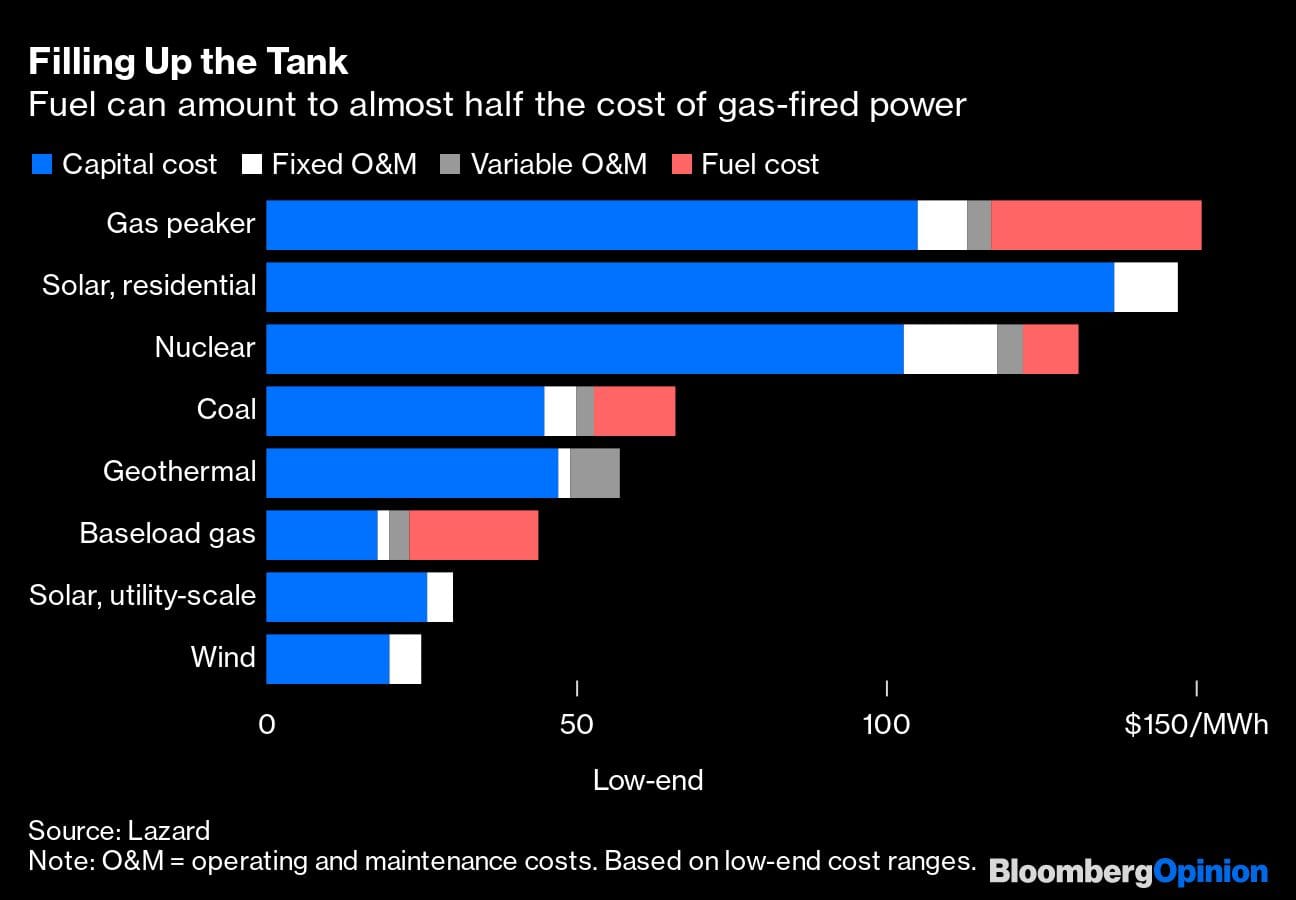

As the name implies, fossil energy depends on fuel. Expenditure on buying hydrocarbons year-in and year-out to power conventional engines and turbines makes up a significant share of overall expenditure. A new Ford Motor Co. F-150 pickup will cost $34,000 to buy, but drive it around for 10 years and you’ll have spent $25,000 just filling up the tank. A gas-fired power station that makes a profit selling electricity at $45 a megawatt-hour is spending almost half that amount on the methane it burns.

The fuel that renewables need, however — wind, sunlight and water — comes free of charge. (Nuclear, whose modest fuel costs are dwarfed by the expense of building a new plant, is in a similar situation.) As a result, the expense of building zero-carbon power is front-loaded and paid off over the lifetime of the project, whereas conventional power incurs a larger share of costs later, at the same time as it’s bringing in revenues. That makes finance critical. Just as fossil energy is fueled by hydrocarbons, renewables are fueled by credit — and when the cost of credit rises, renewables’ economic advantages diminish.

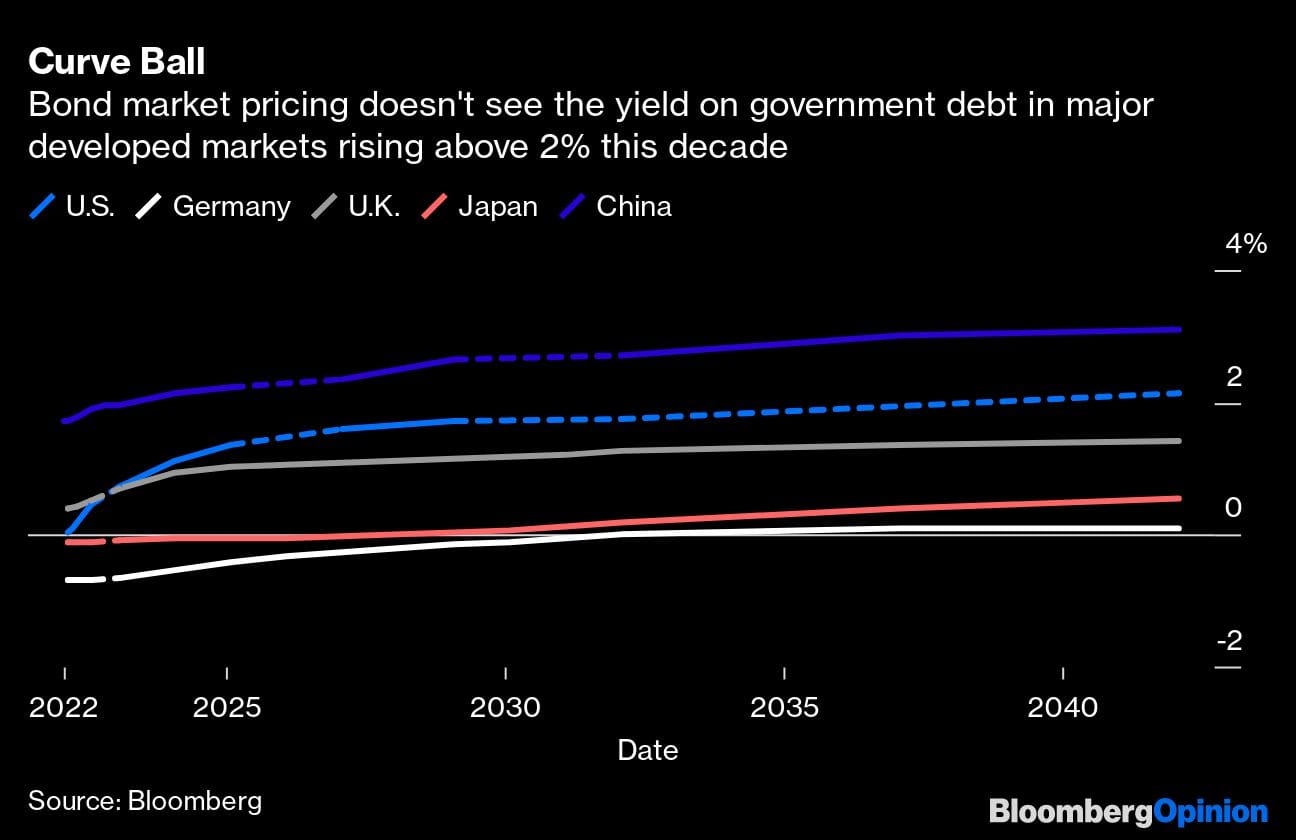

Just how much is open to debate. One 2019 study of German renewable projects estimated that if 10-year government bond rates were to climb to 4.3% by 2023, the costs of solar would rise by 11% and those of wind, 25%. That would be enough to reverse the situation seen in recent years where new unsubsidized renewables have been able to undercut existing black coal and gas generators on cost, they wrote.

That, to be sure, would be an extreme scenario. German government debt is still trading at a negative yield and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., one of the most hawkish Fed-watchers at present, doesn’t foresee the U.S. Federal Funds Rate climbing above 2.75% in forecasts stretching out to the end of 2025.

Higher interest rates, meanwhile, are both a cause and an effect of higher energy prices, so it’s reasonable to assume that if the cost of renewables rises because of central bank policies, fossil fuel pricing would increase as much. An 11% bump in solar looks pretty modest next to the four fold increase in European gas benchmarks over the past year, and even that would only slow, rather than arrest, the advance of renewables thanks to their ever-declining equipment costs.

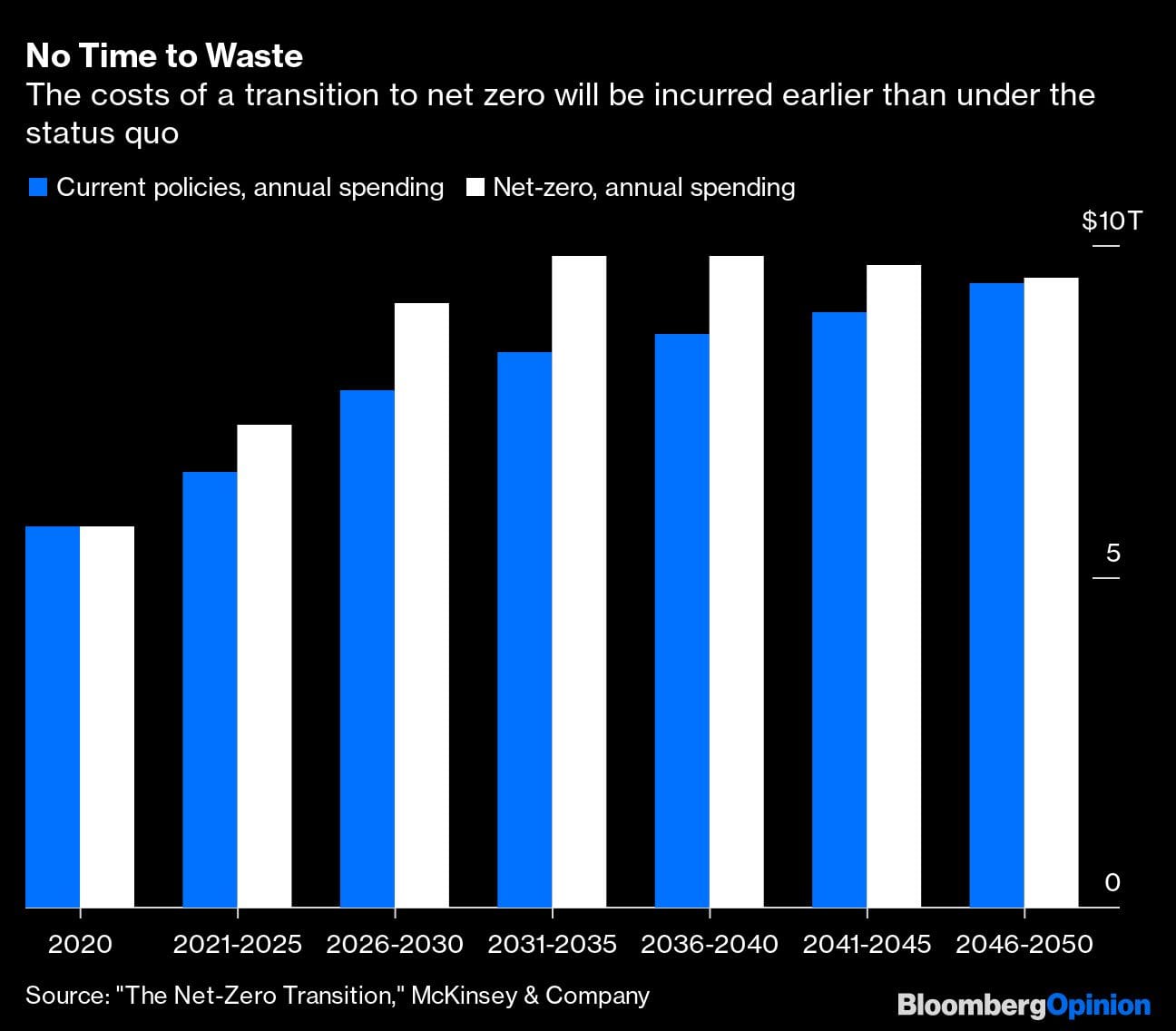

At the same time, it’s important to consider whether shifting so much expenditure to the near term could have its own macroeconomic effects. Current spending on energy and land-use assets amounts to about $5.7 trillion a year, according to a McKinsey & Co. report last month. A shift to net zero would increase that spending over the coming three decades by a cumulative $26.5 trillion, the authors estimated.

That’s a modest outlay when set against the $19.5 trillion in borrowing incurred over 12 months in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Still, about two-thirds of the increase in spending will have to occur over the next 15 years, according to McKinsey.

One explanation for the current era of low rates is that a generation has been deferring its spending to pay for longer retirements. This ballooning savings pool, chasing returns from a slower-growing pile of assets, has pushed down the cost of borrowing across the board.

The investment needed for a successful energy transition might change that. McKinsey’s estimate for spending on carbon-exposed assets equates to about one dollar in 15 in the global economy. Drag those costs forward and the long-term effect may be deflationary — but in the near term, that pool of savings may finally find the assets it’s been seeking, sending interest rates to a structurally higher level than we’ve seen for many years.

The twin fuels of the modern economy are energy and credit. Energy price volatility has always been a driver of macroeconomic policy, all the way back to the days in the mid-20th century when a sharp increase in the oil price was seen as an inevitable precursor to recession. In the past, though, that uncertainty has been driven only by supply-demand mismatches within the oil market. In the future, it may come from structural changes in the way our entire planet generates and uses energy.

Central banks wrestling with whether to use their economic clout to reduce the cost of capital for green investments should take note. Pushing too hard on interest rate rises could undo all the good they’re trying to do elsewhere. –Bloomberg

Also read: India marks 1,000th ODI with convincing 6-wicket win over West Indies in Ahmedabad