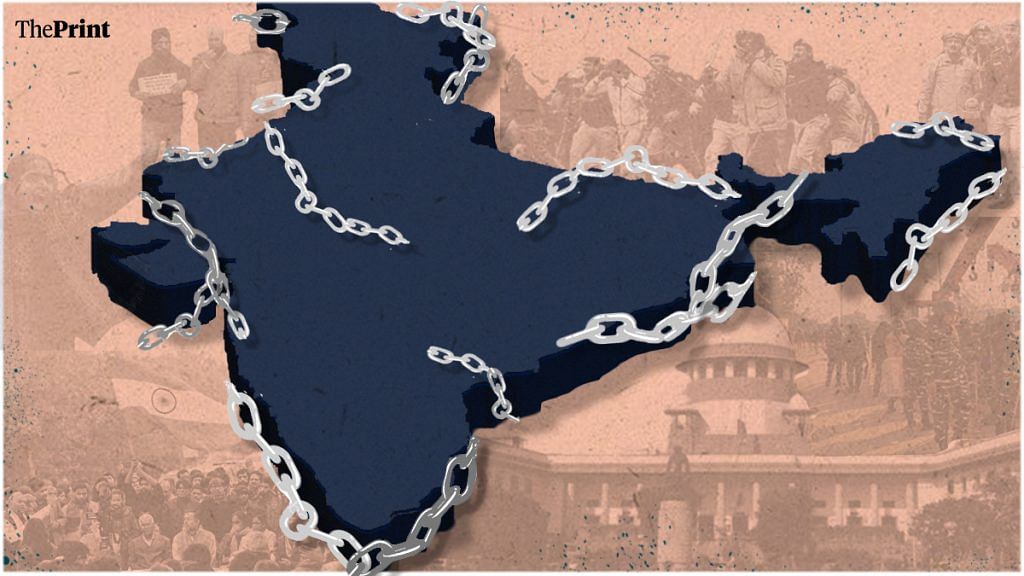

Control-oriented regimes tend to adhere to strikingly similar playbooks. Xi Jinping, for instance, has said that “East, west, south, north and the centre, the party rules over all”. That echoes Mussolini’s sharper formulation: “Everything in the State, nothing outside the State, nothing against the State.” India is not where those regimes are or were, being “partly free”, as a US-based NGO (non-government organisation) describes it. But the Narendra Modi government’s desire for steadily greater control of so far autonomous centres of influence and activity makes clear the direction in which the country is headed.

The rules released last week for what is called social media are only the latest manifestation of this desire. The global tech companies that own, control, and regulate (in a manner of speaking) social media platforms now face pressure to cede ground to the government, with implications for individual privacy. Subsequent revelations about the preparatory work that went into including the digital news media in the ambit of the new rules make clear the intent to “neutralise” dissident voices.

Other areas of mass engagement, like sports and entertainment, are also targets. The control acquired of cricketing bodies, and the virus of communalism that seems to be getting injected into the country’s most popular sport, is one manifestation and of greater consequence than the renaming of a stadium. Meanwhile, politically aligned divisions have been engineered in the personality-driven world of Hindi filmdom (regional-language film worlds have been politicised for decades).

The tentacles spread wider. The capture of a dominant share of political finance has been achieved through the facilitation of corporate funding via anonymous donations. Meanwhile, civil society outfits find their sources of funds being squeezed. And the first move into the watering holes of the Lutyens in-crowd has been facilitated by the takeover of the management of the Gymkhana Club.

Such initiatives are relatively easy because of the poor governance norms practised by most civil society entities. And all too many individuals critical of the establishment seem to have the Achilles heel of tax evasion. The Gymkhana Club, for instance, had fallen foul of the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal. Pressure for control or compliance now focuses on one or two other Lutyens institutions and think tanks. Such vulnerabilities serve to blunt criticism that tax raids and other action by the “agencies” are aimed at only critics of the government. But the targeting is obvious and conveys a message.

Also Read: Modi shouldn’t echo Xi’s policies because India isn’t China on so many levels

A predictable battleground is higher education. Two of the highest-ranked educational establishments, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Jamia Millia Islamia, have felt under siege in different ways, but they are not the only ones. The preferred method of control seems to be the appointment of carefully chosen vice-chancellors who will impose change from above, but police action too has been used to good (if that is the word) effect.

Meanwhile, the re-writing of school textbooks continues, with such changes as the erasing of Nehru’s name from contemporary Indian history.

Sometimes the government oversteps, as with its order on the requirement of prior approval for those wanting to take part in online scientific seminars, and withdraws. It may have to do the same with its new rules for the digital news media, given the constitutional guarantee of free speech — though the courts are no longer predictable on individual liberties. How far the government will go in its set direction depends on the effectiveness of domestic institutional resistance and on how much it wants to risk international censure.

Meanwhile, Rahul Gandhi should brush up on his history if he believes that the Emergency was a “mistake” (like jumping a red light, perhaps), and that the Congress did not seek to capture institutions. He should read up on the supersession of independent Supreme Court judges, the talk of needing a “committed” bureaucracy, and the steady packing of academia, research bodies, and cultural organisations with ideological fellow-travellers. Tolstoy is often quoted for his line “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”. Similarly, autocratic regimes tend to be alike, irrespective of party tag, time, place, and context, though each repressed polity may be unhappy in its own way.

By Special Arrangement with Business Standard.

Also Read: As India returns to positive growth, it must think why it can’t remove poverty like China has