City rankings are a flourishing business. The Economist Intelligence Unit has put out its latest this week, on the most expensive cities and the cheapest ones. Ahmedabad figures in the Top 10 of the latter, in the undistinguished company of places like battered Damascus and Tripoli. Earlier the government put out its update on India’s cleanest cities, with Indore once again claiming top honours. The government also puts out its list of cities ranked on ease of living — Bengaluru tops, followed by Pune, while Srinagar and Dhanbad are the worst. A similar listing by the Centre for Science and Environment also puts Bengaluru at the top, followed by Chennai (which is fourth in the government ranking). A smart city ranking may soon be on its way, if one has not already been done, since a complicated set of criteria has been spelt out.

Some trends are easy to spot. The big metros don’t rank well — in India or internationally. Mumbai and Delhi (and Kolkata for that matter) rarely rank high, while internationally the most liveable cities have been mid-range ones like Vienna, Auckland, and Vancouver — though Melbourne did very well for a long stretch. The biggest European, American, and Chinese cities are not the most liveable, partly because they usually have the most expensive real estate. In addition, there are the usual problems of commuting time and pollution. Japan maintains the trend, in that Osaka outscores Tokyo.

A second trend is that cities south of the Vindhyas do well (no surprise there!), plus the big three of Gujarat. For cost of living as well as healthcare, two of the seven metrics used for a global ranking on Quality of Life, places like Mangaluru, Coimbatore, Chennai, and Thiruvananthapuram score well. That is within the larger context of Indian cities mostly tending to figure in the third quartile from the top. This unimpressive showing is influenced by poor income levels and the hot weather. Many of India’s best cities are therefore on the Deccan plateau, giving them an elevation that makes for a less forbidding summer. Indore is at the edge of the Malwa plateau (elevation: 1,800 feet) while Coimbatore (1,350 feet) gives easy access to the Nilgiris.

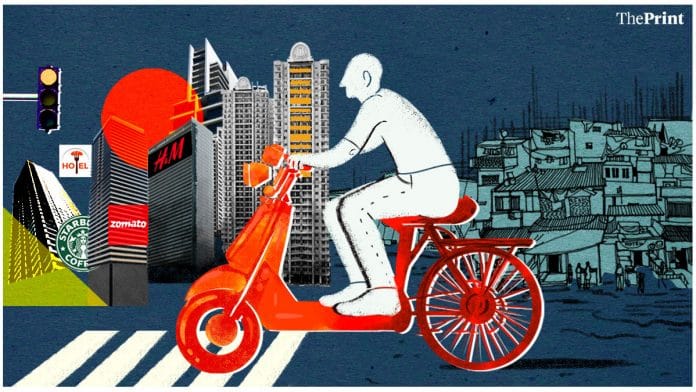

If India is to urbanise successfully, it has to focus on these Tier 2 cities with a population of 10-50 lakh. Some of them are getting attention in the government’s Smart Cities programme, which is fine but inadequate without structural changes like directly elected mayors, a sensible property tax system, designs for being made citizen- and bicycle-friendly, and rules for floor-area ratios to enable high-rise office towers, required to create a central business district and avoid urban sprawl.

Also Read: Vir Das was right, there are 2 Indias, and they aren’t getting any closer together

A lesson

But there is also a lesson in the fact that the big metros, though they fare poorly on Quality of Life, continue to be magnets for latter-day Dick Whittingtons. Indeed, the standard feature of successful cities is that they welcome people from elsewhere, which is why Mumbai has so many Gujaratis, Parsis, South Indians and, once upon a time, Baghdad Jews. It is also why Delhi has become less Punjabi-dominated, and why Kolkata in its heyday had so many non-Bengalis, including Chinese, Armenians, and others. It is this mix that makes metros more interesting and cosmopolitan, while smaller cities stay provincial.

Bengaluru is an interesting case study. It is outranked by Coimbatore and Mangaluru on many metrics (e.g. pollution, healthcare, safety), yet it usually ranks at or near the top as the most liveable, despite having acquired the problems of a car-oriented metropolis. Its climate, cosmopolitan air, affordable real estate, and high rating on the purchasing power index (presumably because of its tech-powered elite) make it the city of choice for those who wish to escape Mumbai’s real estate prices (rated among the most unaffordable in the world, relative to income) and the poorly ranked Delhi-Gurgaon-Noida. Yet, the fastest growth is in the Tier 2 cities — Surat’s population has increased by an average of more than 70 per cent for four decades. The success or failure of India’s future urbanisation will be written in such cities.

By special arrangement with Business Standard

Also Read: India has turned to survival of the fittest under Modi, but needs ‘survival of the friendliest’