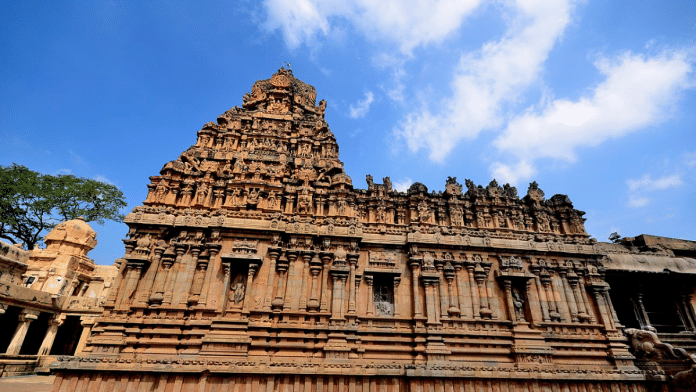

South India’s towering temple gateways and gopurams are among its most iconic architectural features. They glitter on tourist brochures and pricey coffee table books. But why are gopurams not a thing in North India? Why do so few medieval temples survive in the North? To some, the answer is straightforward: “Islamic” invasions wiped out North Indian temple worship. However, the real causes are more complex. Financial and social appeal, as much as devotion, created South India’s glorious gopurams.

Who built temples and why

Hindu temples today are many things, but primarily religious and community centres. They’re part of our lives, where we ask gods for aid or favour and express devotion. We go to temples for festivals to sing, pray, or watch performances. But was this always the case?

An overwhelming amount of evidence from medieval India says: No, not always. We know this from two sources. The first is architectural — crowds of devotees require open areas, large roofed compounds, and facilities for water, food, and access to the gods. You see this in contemporary temples. But the earliest surviving medieval temples, from the 5th–6th centuries CE, were tiny structures in walled-off compounds.

The second type of evidence comes from inscribed temple donations. Many temples today have plaques advertising patrons and devotees from a diverse cross-section of society. In contrast, inscriptions on early medieval temples suggest they were built and maintained by courtly aristocrats. There may have been humbler shrines of thatch and wood where poorer communities worshipped their own divinities. But elaborate stone temples were generally built by royal courts to facilitate rituals for their own benefit. There’s little evidence that early temples were community centres for all Hindus, as we often imagine today.

How, then, did temples become social hubs, as they are today? It’s here that North and South India diverge.

Let’s look specifically at Tamil Nadu, which has some of the most impressive gopurams and the most sprawling complexes often extending to over a hundred acres. From around the 8th century onwards, something radically impacted the evolution of Tamil temples. This was the bhakti movement, when Tamil poet-saints began to sing the glories of Shiva and Vishnu, describing the gods as actually living in various Tamil towns and villages. Within the next century, as historian Vidya Dehejia writes in The Thief Who Stole My Heart: The Material Life of Sacred Bronzes from Chola India, 855–1280, we see a very different kind of temple patronage in the state. In the 9th–10th centuries, everyone from shepherds to washerpeople, gentry to aristocrats, were making gifts and renovating shrines. And in comparison to North India, where most temple rituals were conducted in elite Sanskrit, Tamil temples had a strong tradition of Tamil bhakti singing, tying gods and temples intimately to local communities.

Also read: When did large Hindu temples come into being? Not before 500 AD

Transformations and expansions

This is not to say that Tamil royals didn’t try to build their own exclusive temples—they absolutely did. But, overwhelmingly, those are not the temples that continued to grow and expand all the way to the present.

You see, to remain in active worship, temples required constant infusions of land, labour, and materials. Kings such as Rajaraja I Chola (r. 985–1014) and his heir Rajendra I (r. 1012–1044) built two colossal temples dedicated to forms of Shiva named after themselves. Yet, after the decline of the Chola dynasty, these temples barely received any gifts for centuries, and their lands and properties were infringed upon and re-dedicated.

Contrast this with other medieval Tamil temples such as Srirangam and Chidambaram. They had their own regional and community loyalties and received gifts not just from kings, but—crucially—from local gentry and magnates. In Tamil Nadu from the 12th century onwards, as studied by historians James Heitzman and Noboru Karashima, gifting lands to temples also brought tax concessions. This, coupled with local loyalties, ensured that they were maintained by their communities through the centuries, no matter who was ruling.

Popular Tamil temples remained relevant through social and economic upheavals. In the 12th century, it was martial families who patronised them. In the 14th and 15th centuries, as the global textile trade grew, weavers became patrons. By the 18th century, as global merchant capitalism boomed, Chettiar merchants took over. As many groups concentrated their activities here, enormous gopurams were built, and patrons competed to gild roofs, add halls, and pay for processions and services in their local temples. Expanded temples brought larger crowds; larger crowds brought more gifts and paid for further expansion.

Also read: Vijayanagara was the Indian Renaissance State. It contains memories of older empires

The North Indian picture

Why did this not happen in North India? In his book chapter ‘Religious and Royal Patronage in North India’, historian Michael Willis points out that local communities did occasionally build temples. But patronage, at least according to inscriptions, was primarily an elite affair of the Sanskrit-speaking courts. The most spectacular medieval North Indian temples—like those at Khajuraho—were built by courts and abandoned when their dynasties collapsed. Generally, in North India, conquerors preferred to build their own shrines, rather than renovate that of a previous dynasty. In South India, meanwhile, kings competed to expand older temples like Srirangam because they were tied to local communities rather than local dynasties.

Some temples were also targeted by invading armies. For example, the Deccan emperor Indra III (914–929 CE) attacked the temple of the goddess Kalapriya when he invaded North India (Epigraphia Indica VII, page 43. North Indian dynasties that struggled politically could not repair attacked temples. In the 11th century, when another Deccan emperor, Someshvara I (r. 1042–1068), invaded Madhya Pradesh, he disrupted the construction of the Bhojeshvara temple at Bhojpur, which, if completed, would have been the largest temple built in North India until the 1700s. After this Deccan invasion, the Bhojeshvara temple’s patrons never recovered, and the temple remained unfinished. Such invasions, coupled with North India’s own internecine warfare, were partially responsible for the abandoned medieval temples still visible in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Gujarat. Without the support of their communities, many of these temples were simply never rebuilt.

The Gangetic Plains, too, saw internecine warfare and South Indian invasion. Unlike the regions mentioned, there are almost no medieval temples here dating to before 1500. There can be no doubt that Sultans were partially responsible for this. From the 12th century onwards, Sultanate attacks here disrupted monastic networks and destroyed any royal temples that were actively in worship. This, as we’ve just seen, was different in scale—not in concept—from older trends. And despite the Sultans’ colourful claims of destruction, it’s very doubtful that they had the capacity to actually do all that, as argued by Pakistani historian Fouzia Farooq Ahmed in Muslim Rule in Medieval India. What, then, happened to all the Gangetic temples?

Gangetic temples were most often built of brick: Once abandoned, they were often mined by locals for building materials or buried under the ever-shifting alluvial soil. North India is still littered with unexcavated archaeological mounds, especially in UP and Bihar. Further studies will continue to complicate the picture.

Diverse histories, diverse religions

India’s diversity is not just a slogan. Diversity means varying historical trajectories, conceptions of religion, and social behaviours. The crucial factor for a temple’s survival was not whether it was attacked by invaders or whether its royal patrons disappeared. Temples survived if they commanded local loyalties and had a reputation as a sacred site, which insulated them from political, religious, or social turbulence. South Indian temples took the form they did because of their precocious vernacular bhakti movements, which shaped the region’s understanding of temples for centuries. As always, in our politics, a phenomenon that seems superficially to be caused by Muslim rulers turns out to have a far more complicated history.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

The real question is why is there no temple older than 18 th century in Pakistan and north India. Even though most of Holi places in India are in north India. Further India has always been around temples. Go to any major temple. For ex. Puri jagannath mandir.people live around the temple. They make a temple and live pray around it, not otherwise. This article is proof why there are so many pseudo Hindus and how so many people got converted.

Mr. Know-it-all at it again. He is not a professional scholar. But writes as though he knows everything.

Sample this, South Indian temples are larger because of investment purposes and not Islamic invasions. The straight forward implication is that Islamic invaders didn’t find any large and grand temples in North India to destroy! because they were not build in the first place (!) due to finances!! So the bhavya Ram mandir rebuilt recently is a fraud on the people because there never was a bhavya Ram mandir in the first place for Babar to destroy. Babar probably destroyed a pidly little Ram temple.

What about all the grand Buddhist (e.g. Borobudur) and Hindu (e.g Angkor Wat) temples in south-east Asia. They represent North Indian or East Indian influences and not South Indian influences. So grand temples were built abroad even though North India didn’t have any grand temples!!

With this kind of logic, it is not surprising that he is no scholar but is holding forth in the media. Nobody should take his articles seriously. He needs a large dose of humility.