The Indian State, like many post-modern neoliberal states, takes support from various non-state organisations and consultancies to address public policy-related issues. Through different types of contractual as well as informal arrangements, state and non-state actors come together to ‘think’ and ‘act’ on critical matters of public interest such as health, climate change, social justice, environment, labour, and education.

This growing dependence on non-state policy assistance is aligned with the Indian State’s vision of ‘minimum government, maximum governance’. A common thread that connects the state and several of the prominent non-state policy actors is capital. Critics argue that this collaboration allows the vested profit-oriented interests of the state and capital to supersede concerns of people on the ground. Experts have also been critical of the State’s conduct in such alliances, highlighting how such arrangements contribute to an image-driven, publicity-based, and brand-conscious model of governance.

In light of this, we take a deeper look at the Indian public policy system by dissecting how state and non-state actors interact in driving public policies. But before delving into this, it’s useful to reflect on the purpose of public policy in general through the words of some of the founding figures of independent India.

Gandhi’s famous talisman reminds us that public policies should focus on benefiting “the poorest and the weakest”. Ambedkar’s vision of an ideal society—built on the tenets of liberty, equality, and fraternity—suggests that public policies should create a society that’s “mobile and full of channels of conveying a change taking place in one part to other parts”. And finally, Tagore’s timeless lines from Gitanjali call for creating a country where “the mind is without fear and the head is held high; where knowledge is free… where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit.”

Power, policy & the ‘hybrid’ Indian State

The economic reforms of 1991 acted as a catalyst for the ‘retreat’ of the Indian State, as it began moving away from its social responsibilities to make way for private capital and actors. Some experts have described the Indian State as ‘porous’, referring to its permeability to business actors and commercial ideas in matters of public interest. Others have termed it as ‘weak’, given the rising importance of private capital and actors in governance. However, there’s more to it. Scholars have also used the attribute of ‘cunning‘ for pointing towards the phenomenon where the state’s portrayal of itself as ‘weak’ is actually an attempt to avoid accountability to citizens and civil society.

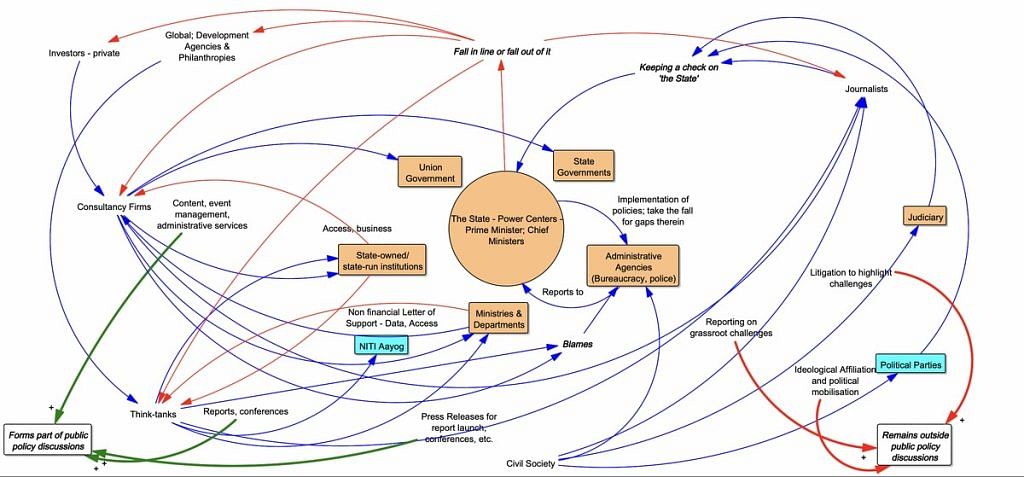

The ‘hybrid State’, as we refer to it, is not just an assemblage of formal and informal actors, but also an idea that shapes the processes and outcomes of policymaking.

Structurally, the hybrid State in the public policy system comprises multiple actors, including governments, state-run institutions, administrative offices, judiciary, political parties, civil society groups, media organisations, private corporations, consultancy firms, think tanks (including NITI Aayog), development agencies, and philanthropic institutions.

These entities interact with the State through written consultancy contracts, legal agreements, memorandums of understanding, and other formal instruments. Such agreements grant private professionals access to government offices, datasets, and various forms of support in exchange for delivering pre-decided outputs, including reports, policy drafts, conferences, and convenings. By lending their support and logos, governance actors confer a sense of importance and political proximity to private actors—something highly valued in the public policy space.

In addition to structural hybridity, the contemporary Indian State can also be seen as an idea that seeks to concentrate power in a few hands. This ‘hybrid State,’ driven by the political executive, operates through a blend of strategies—reward-based and coercive.

Rewards may include plum postings, advisory roles, or post-retirement benefits for officials who conform to the wishes of the political executive. For private institutions, rewards also encompass financial perks, a sense of power, or the image-boost that comes from working with the government. However, these rewards often come with a high degree of content moderation—where the language of reports and policy outputs must promote or glorify the government’s initiatives. Some institutions do this promotion outrightly, while others attempt to strike a fine balance. Private actors who do not conform to the government’s vision risk having their work discredited or, in some cases, facing criminal charges and being labelled as ‘anti-national’.

Given this context, we’ve identified four troubling attributes of the current public policy space.

One, they tend to promote technical fixes for deeply complex socio-political and environmental challenges. A case in point is pushing electric vehicles as a technological solution to transportation issues, without addressing the deeper structural problems. These include affordability, quality of services, socio-economic vulnerabilities of commuters, and addressing the transportation needs of people, particularly in peri-urban and rural contexts.

Two, they are usually blind to power dynamics, failing to address why the current socio-environmental challenges exist and persist. For instance, while promoting the policy narrative of a just energy transition, such actors fail to shed light on who benefits from an unjust energy system in the first place, or why and how this is so.

Three, many of their policy products are centred on research done from Delhi or other metropolitan cities; they often seem to be socially detached from realities on the ground. Even those that attempt to inform policies through grassroots evidence tend to reduce complex social concerns to measurable indicators and metrics. In the energy sector, for instance, issues of justice are widely assessed through job numbers, while qualitative concerns around dignity, fairness, resource grabbing, and other such matters are strategically sidelined.

Finally, many of these policy products appear to be based on flawed or weak philosophical principles. It’s often unclear whether their research and recommendations are based on majoritarianism (the maximum benefit for the majority), utilitarianism (maximum benefit for the greatest number of people), deontology (the idea that the means do not justify the ends), or virtue ethics (where the focus is on the moral intent of agents driving change).

A pictorial representation of this hybrid State’s manifestation in Indian public policy system is shown here as well:

Breaking free

A detrimental and fragmented public policy system is dangerous for several reasons. One of the less discussed reasons is that this system also sends a market signal to institutions shaping the next generation of policy professionals. It’s resulting in a situation where such institutions are prioritising skills such as communication, networking, publicity, ingenious number-crunching, alongside the socially and politically blind promotion of technologies. This casts a dark shadow on the ethical foundations and philosophical inquiry that are central to the social sciences.

The outcome we are witnessing is that students of social work and humanities are competing with highly paid business graduates in a domain that should be about speaking truth to power and acting as a bridge between voices from the ground and those in policy and governance corridors.

Raj Kamal Jha, the editor-in-chief of the Indian Express Group, once said, “Criticism from the government is a badge of honour for journalists”. The same realisation is needed in the contemporary public policy space as well. The suppression of rights and media freedom during Emergency is often alluded to by the phrase, “when asked to bend, they started crawling”. We believe that this is currently the case in India’s public policy arena as well.

Suddenly and magically growing a spine in such a highly controlled climate is not a realistic solution. It requires a deep understanding of the entire system—its ‘what, why and how’. To build a public policy sector premised on the ideas of Gandhi, Tagore, and Ambedkar needs a united effort. We call upon champions of free, fair, socially centred, ethically sound, and philosophically grounded policy reform to help break the shackles of the sarkar-bazaar nexus from the bottom up— like a billion fireflies emerging to spread light in dark.

Sarthak Shukla is a doctoral student at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala Sweden. Arun Maira is a thought leader, former Member, Planning Commission of India and Chairman of HelpAge International. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Whatever arrangements a state may make, with private enterprises, it is ultimately accountable to public. It cannot hoodwink for long, or escape the realities of elections.