Browsing through the newly opened Humayun Museum in New Delhi was surreal. It felt as though the last ten years hadn’t really happened in Indian politics. It lulls you into thinking that history is not the bitterly contested ground that it has come to be recently.

The 16th century Mughal ruler, Humayun, was the son of Babur. And we know by now how dreaded and despised Babur’s name is in Indian public imagination. So, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture’s new museum in collaboration with the Archaeological Survey of India, and inaugurated by the Ministry of Culture, is truly a counter-intuitive curation.

What’s missing in the museum is as important as what is present.

Here, at this beautiful underground museum, Akbar is ascribed the suffixes ‘Great’ and ‘Greatest’ without any trepidation. Humayun is an art-lover and empathetic emperor, while Mughal architecture, music, literature, arts, and astronomy are celebrated. This site museum exists in completely the opposite direction of what has been going on politically and being said by the new opinion-makers on X, Facebook, and YouTube. It’s like I was sent back to my school history textbook from the 1980s, with its rendition of the Mughal era minus the frothing and the bitterness.

As a museologist, I am trained to regard museums as safe spaces for unsafe ideas. And it is indeed unsafe to recall the Mughals’ contribution without talking about jazia, conversion, invasion, and loot in today’s fraught times. How I Got Away With Museums should be the real title of this series.

It isn’t just truly curiosity-inducing but also almost incredulous how the museum worked so closely with the government and presented a curative ideology that defies the dominant political narrative. For me, the ‘what’ of the museum is less interesting than the ‘how’. As in, how did this come about?

This is not to say that the Humayun museum isn’t sticking to the facts. It is. But it is value-neutral and appears to have not registered the politically loaded terms that have accrued to historiography in recent years.

Museums shouldn’t get dragged into partisan politics; that is how they should be. But, being tone-deaf to the political cacophony outside the museum is also a deliberate political act. And it requires curatorial conviction.

The word ‘invasion’, which has come to be so closely tagged to the Mughals, is conspicuously missing. Instead, the museum speaks of the Mughal ‘legacy’. At the outset, an exhibit titled ‘Where the Emperor Rests’ features an impressive audio-visual presentation that innocuously calls Humayun’s military conquests “Humayun’s journey 1508-1556”. It is completely value-neutral, similar to a monument I saw in London that described 1857 as a ‘campaign’, or in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, where Timur’s invasions into India were termed a campaign. “Without Humayun, there would never [have] been a Mughal legacy”.

Also read: Humayun pioneered architecture, art, and astronomy. Now he’s got his own museum

The story of Humayun is lovingly told in the museum – how he missed Hindustan when he was sent by father Babur to Badakhshan; how he was defeated by Sher Shah Suri and sought refuge in Iran and unceasingly plotted his way back to the throne of Hindustan after 15 years; how he nearly drowned in the Ganga at Chausa and was rescued by a water carrier; how he was the ‘planetary king’ who studied the astrolabe and invited scientists from Samarkand to set up a workshop to make astronomical instruments; and how he was the ‘warrior-emperor’ who began at the age of 18 to fight alongside his father Babur’s ‘military campaign’; and when he became king himself, he led a series of ‘victorious battles’ to expand the Mughal Empire across Gujarat in western India and in Bengal to the east.

A text panel, titled ‘Humayun’s Life of Travel’, says: “Humayun travelled 34,000 kilometres during his life as a warrior, criss-crossing present-day India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran, seeing more of the world than any other Mughal emperor. His travels took him to over 100 cities stretching from Tabriz on the edge of Europe to Gaur in Bangladesh.”

In one video exhibit, titled ‘Buland Shaksiyat’, Humayun is presented as an art-lover, an astronomist, an explorer, and a compassionate empire-builder.

Also read: National Museum guards, guides aren’t just worried about artefacts—’Will I have a job?’

‘A deep-rooted cultural matrix’

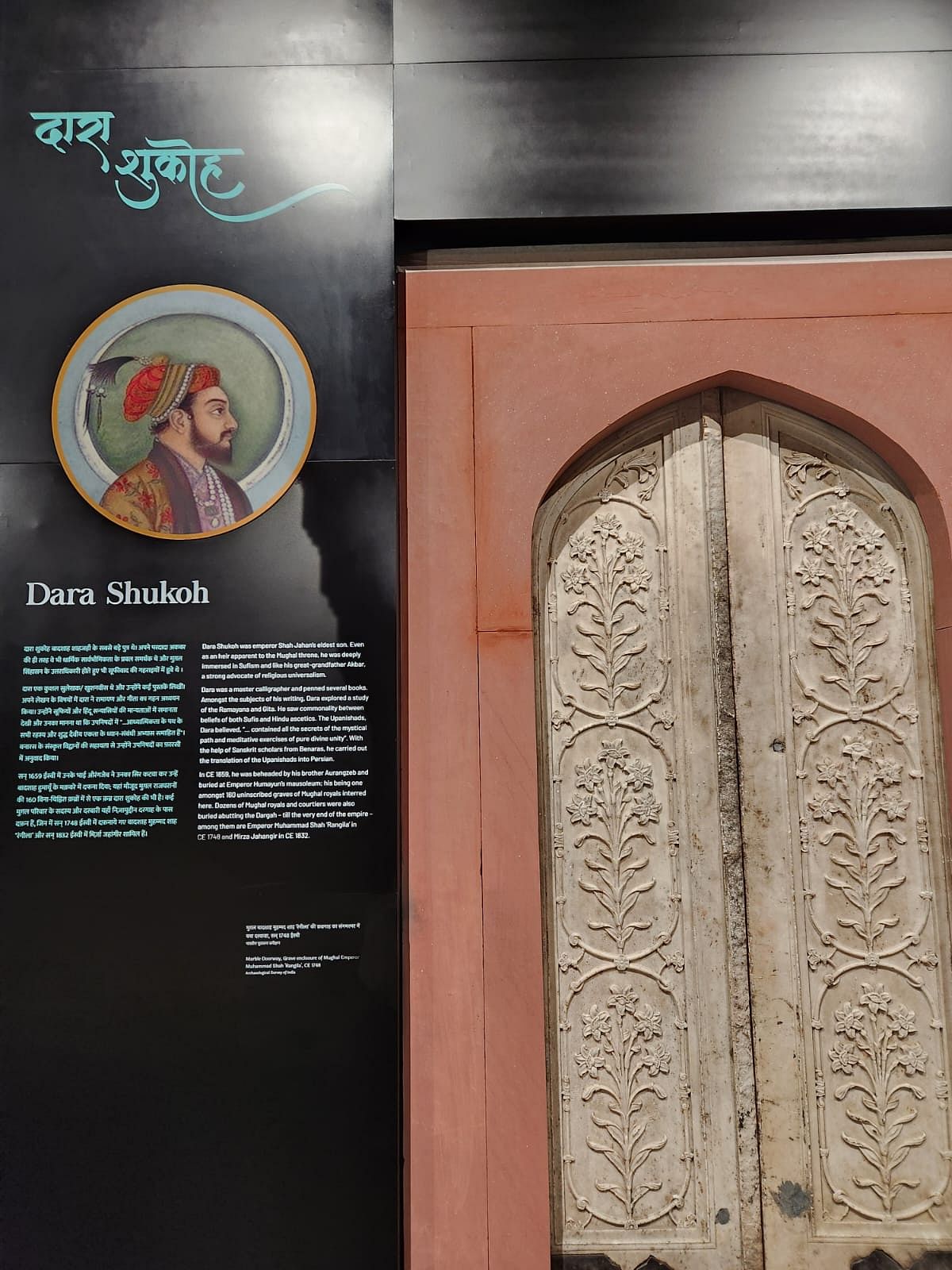

The storied Ganga-Jamuni culture is on full display at the museum. In fact, it perfectly and subtly weaves together old and new emphasis in historiography. Without aggressively paying tribute to the syncretic culture that the Mughal period presided over—a usage many today frown upon—the curation subtly foregrounds figures of syncretism. Dara Shikoh, a favourite in the current government’s cultural projection, gets his rightful place under the sun. His is one of the dozens of unnamed graves at the Humayun tomb site.

Dara Shikoh’s discovery of the Upanishads in 1657 and its translation is prominently displayed in a very compelling exhibit called ‘Upanishads: The Hidden book’ – a long-ignored focus in our history museums. He described the work as one “in which are contained all the secrets of the mystical path and meditative exercises of pure divine unity’. The text panel says that Dara Shikoh believed the verses of the Quran could be found within the Upanishads. He worked with Sanskrit scholars from Benares to translate them into Persian. The exhibit also displays Nastaliq script calligraphy written by him and a farman (official decree) with the official seal of Dara Shikoh.

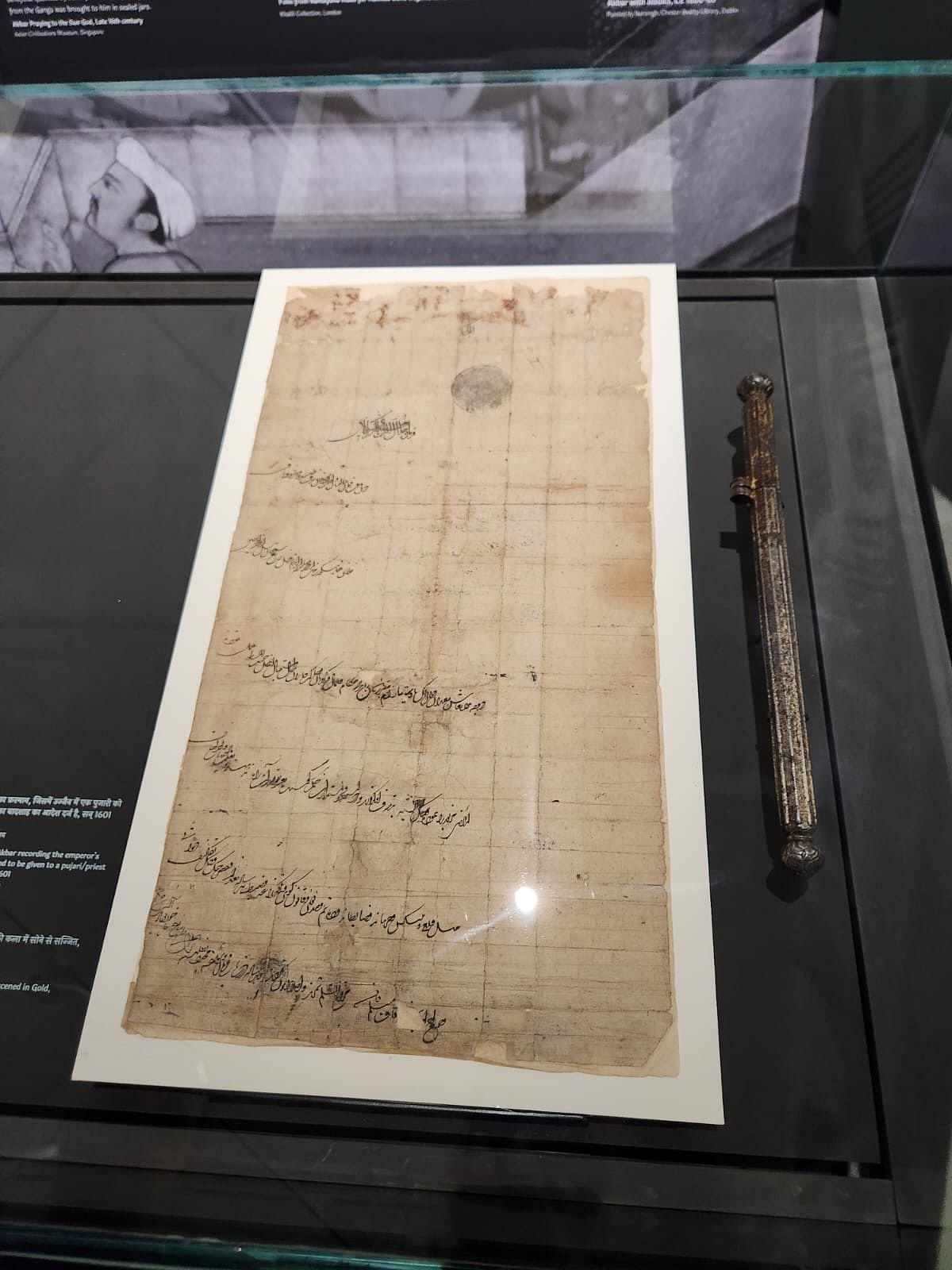

There is a 1601 handwritten farman of Akbar ordering his state to give land to pujaris from the National Museum.

The museum also has a life-size replica of Nizamuddin Aulia’s marble tomb, and even has a screen with red threads of wishes tied around it. Qawwali music plays in the background along with vitrines of manuscripts and books about the sufi mystic. Next to these is a 14th century stone inscription called ‘The Hadith’ accessed from the Archaeological Survey of India. Through Hazrat Nizamuddin’s life, Hadith literature remained one of his most favoured fields of study.

Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanna, the commander in chief in Akbar’s army, gets an exhibit all unto himself – highlighting his patronage of poetry, the arts, calligraphy, bookmaking, and of the translations of the Ramayana.

There is an exhibit to Amir Khusro and his beautifully illustrated folios, along with Rumi’s book of poetry, Masnavi.

At the inauguration, Tourism and Culture Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat called it “deep-rooted cultural matrix” and mentioned the display of Dara Shikoh’s Persian version of the Upanishad alongside his Quran, and Rahim’s couplets inscribed on the walls alongside his translations of the Ramayana.

Also read: Delhi’s Partition Museum remembers pain of separation—through artefacts, images, personal items

A break from sarkari museum template

The museum is special because it is a storytelling museum and isn’t just dry and object-centric like the National Museum. It allows the visitor multiple entry points to the story of Humayun and the Mughals. It marshals miniature paintings, exquisite gilded manuscripts, artefacts, and archeological finds such as doorways, pieces of pillars, and screen windows.

In other museums, these items would typically be scattered across different galleries—miniature paintings would be a separate galley, built architecture would be found in a different space, and manuscripts would be a whole exhibition by itself. By bringing them all together and placing them along a single timeline and storyline, the Humayun Museum adds depth and richness to its curatorial template. Artefacts have been accessed from the Imperial Library, Royal Collections Trust (UK), the National Museum, the Archaeological Survey of India, and the Aga Khan Trust.

Audio-visual presentations add layers to the storytelling and provide important relief points for the visitor. The three-dimensional immersive film of the Humayun tomb complex at the museum entrance is jaw-dropping. It prepares the visitor for the grandeur awaiting them in the galleries.

There is also an entire section devoted to the gilded copper finial that fell from Humayun’s tomb crown during a May 2014 thunderstorm. The story of how a new replica was made, and the old one restored, reflects a true labour of love by the Aga Khan Trust.

The museum is truly a break from the established sarkari museum template. It is also a very smart curation – especially in today’s charged political climate.

If you are a political animal, then get ready for some cognitive dissonance. The Mughal museum I had imagined the year 2024 will bring to us in Delhi is indeed a very different one. India has not changed that much, after all.

Rama Lakshmi, a museologist and oral historian, is ThePrint’s Opinion and Ground Reports Editor. After working with the Smithsonian Institution and the Missouri History Museum, she set up the ‘Remember Bhopal Museum’ commemorating the Bhopal gas tragedy. She did her graduate program in museum studies and African American civil rights movement at University of Missouri, St Louis. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Also read: The chaiwala-to-PM story is the stuff of museums. But the new Modi gallery fails to tap it