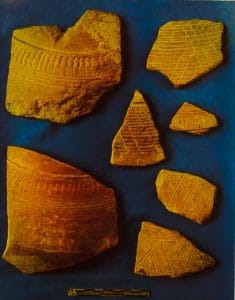

What exactly happened in the subcontinent after the decline of the Harappan Civilisation is a frequently asked question that has nagged researchers and archaeologists for over seven decades. In the absence of any evidence, many proposed that a ‘Dark Age’ followed – a theory that persisted until archaeologist BB Lal and his team excavated the fascinating remains of Hastinapura in 1950-52. They unearthed finely crafted grey pottery, christened ‘Painted Grey Ware’, which was hailed as a marker of the culture that followed the downfall of the mighty Harappans north of the Vindhyas. This grey pottery with beautiful painted motifs was found in the strata sandwiched between an early chalcolithic culture of the Ganga-Yamuna Doab, called the Ochre Coloured Pottery Culture, and the subsequent historical period. Although it definitely bridged the gap between the Bronze/Copper Age and the Iron Age, not much was noted about subsistence pattern, social complex, traditions and practices etc from this particular stratum during the excavation, and what followed was technical confusion.

On a macro level, Painted Grey Ware filled the blank between the Harappan Civilisation and the Iron Age, but in terms of complete direct stratigraphy and even chronologically, there was still a gap of around 400-500 years. There was not one site where archaeologists could find Harappan (especially Late Harappan) strata right below the Painted Grey Ware strata, which, in the absence of a radiocarbon date, could give them a definite clue about life after the decline of the Harappan Civilisation. That is, until Jagat Pati Joshi from the Archaeological Survey of India excavated Haryana’s Bhagwanpura in 1975-76. (Jagat Pati Joshi et al., 1993, Excavation at Bhagwanpura 1975-76 and Other Explorations and Excavations 1975-1981 in Haryana, Jammu & Kashmir, and Punjab)

Also read:

What researchers found at Bhagwanpura

In 1974, Ravindra Singh Bisht, who was Haryana government’s Deputy Director of Archaeology back then, was exploring the state’s Kurukshetra district when he stumbled upon an archaeological mound located 350 metres south of the village of Bhagwanpura. He noticed the presence of Harappan cultural material along with Painted Grey Ware pottery at the site. He introduced it to fellow archaeologist Jagat Pati Joshi in August 1975, who excavated it in the same field season.

Upon excavation, a very low mound surrounded by a few Kikar trees yielded a total archaeological deposit of 3.20 metres, which was divided into Sub-Period IA and Sub-Period IB, based on differences in cultural material. Sub-Period IA yielded Late Harappan (c. 1900 to 1500 BCE) structures built on raised mud platforms. One platform measured 4.25 x 10 metres and was constructed as a precaution against floods. The Late Harappan deposit, as noted by the excavators, was 70 cm to 80 cm, on top of which a thick deposit of flood was noted. Excavators suggested that the Late Harappan occupation was ‘ravaged by a gigantic flood’, which didn’t discourage people from continuing to live at Bhagwanpura.

Despite the flood destroying the entire Late Harappan settlement, the excavators did not find any break between Sub-Period IA and IB, as late Harappan elements continued in this period, along with the introduction of Painted Grey Ware using people. In fact, two layers were marked within this period where there was an ‘overlap’ between the two distinct cultures. The statistical analysis of pottery suggested a gradual decline of Late Harappan elements in the late levels of Sub-Period IB. This was the first evidence of the co-existence of two different social groups, an interesting find that changed and gave impetus to archaeological research in the late 1970s.

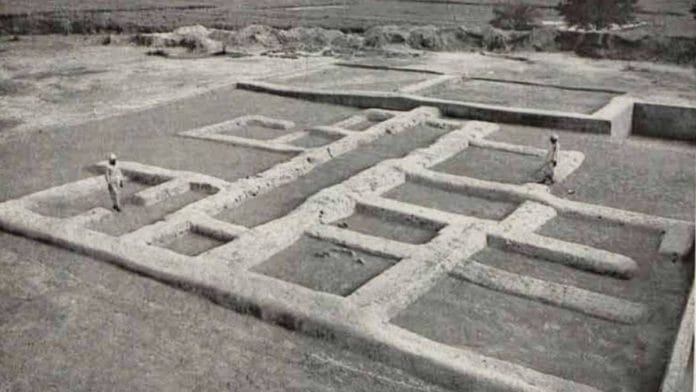

Sub-Period IB, despite the interesting interlocking of the two distinct social groups, yielded impressive structural evidence ranging from round or semi-circular thatched huts of ‘wattle and daub’ (with as many as 23 post holes in one instance) to mud-walled and baked brick houses. The most striking evidence is from the second structural phase, where a complete mud-walled house complex was unearthed in a trench.

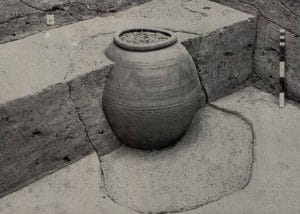

The walls were about one metre thick, which gave an impression of a well-planned house with 13 rooms, a corridor between two sets of rooms and a courtyard on the eastern side. The rooms were as big as 1.60 X 1.60 metres to 3.35 metres X 4.20 metres in dimension. This housing complex also yielded copper objects, faience bangles and beads, terracotta figurines, Late Harappan pottery (around 2 per cent to 5 per cent of the assemblage) and Painted Grey Ware vessels. What one could infer from this interlocking/overlapping in the cultural material is still a matter of research and debate.

Also read:

The significance of Bhagwanpura’s excavation

Before the excavation at Bhagwanpura, the association of Harappans with people who used Painted Grey Ware was unknown. The concept of continuity was blurry, and no one could put the two distinct cultural groups together – especially in the absence of a site where the two showed signs of continuity, change and co-existence in a stratified context. But, in this stratigraphical context, the interlocking of Late Harappan elements with the Painted Grey Ware culture at Bhagwanpura changes the narrative. The thermoluminescence dating of the Sub-Period IA to circa 1700-1300 BCE and Sub-Period IB to circa 1400-1000 BCE further supported the evidence found during the excavation.

However, the buck didn’t stop at Bhagwanpura; Madina in Haryana’s Rohtak district is also one of many important sites that replicated the evidence from Bhagwanpura when excavated in 2007-08.

What remains to be probed are the various aspects of this interlocking that go beyond material culture.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)