Scientific discovery has a momentum of its own. The unravelling of the atom’s mysteries by scientists in the early 20th century is a story with the breathtaking pace and surprise elements of a thriller. One with a dramatic finale bringing together the product of science and the exigencies of war in an explosion of horrifying magnitude.

Christopher Nolan’s latest blockbuster Oppenheimer, a biopic of American physicist J Robert Oppenheimer, who led the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico to build the atomic bomb during World War II, follows this historical arc. But instead of visually depicting the devastating nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the film focuses on the first detonation in the New Mexico desert, a test blast codenamed Trinity, in July 1945.

A milestone in the history of the A-bomb, Trinity tested years of scientific theorisation by the most brilliant minds of the time, an experiment made possible by a high level of organisation involving thousands of people, $2.2 billion worth of resources, and the building of a township on a desert stretch.

In the film, the countdown begins with scientists, engineers, and military men clutching anti-glare lenses and taking their pre-fixed observation posts. It has been a long night. A threateningly disruptive storm has abated. Reckless last-minute manoeuvres ensure that everything is in place. Someone is put in charge of pressing an abort button if things go wrong.

As the audience, we have been made aware that there is a chance, though an infinitesimally minute one, that the explosion could set the world afire. If not an apocalypse, we can be sure that the test is a precursor to something unimaginably terrible. Yet, significantly, in that dramatic moment, we do not think of catastrophe, the future of humanity, or the certainty of genocide. Like the men on their dawn vigil on the sands of New Mexico, we too, are breathlessly eager to know if the damn thing will work.

By choosing Trinity over Japan, Nolan succeeds in drawing attention to the blinding seductive rush of technological achievement — cause rather than effect. It is a bold move with what appears to be deliberate intent.

On the one hand, by suggestively evoking the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki through potent visuals of a sinister white light and hallucinations, Nolan raises the question of moral responsibility.

On the other hand, by not showing affective images of pain and death, he allows for a cerebral understanding of the multiple considerations sparked by the imminence of the bomb.

History tells us that modern physicists were not figures locked in an ivory tower but politically engaged world citizens. Albert Einstein (egged on by Hungarian scientists Leo Szilard, Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner) wrote to US President Franklin D Roosevelt in 1939, urging him to procure uranium ore and speed up experimental work on a nuclear weapon to get ahead of a potential Nazi bomb. The eminent Danish scientist Niels Bohr tried to persuade Roosevelt and United Kingdom’s Winston Churchill to share information with the Soviets in the interest of averting a post-war arms race, a concern shared by Oppenheimer.

Also Read: Oppenheimer joins the ranks of Wolf of Wall Street. A biopic that lionises the hero, no warts

Eroding morality

Nuclear science was a genie that could not be put back in the bottle, and its implications and possibilities were a matter of global concern. The Indian atomic energy programme, established in the late 1940s, for instance, committed itself at least publicly to the peaceful uses of nuclear power. Over the years, however, a need to bolster national pride by proving its scientific and technological prowess to the world whittled away at India’s early ethical stance, raising a clamour for a pro-weapons policy.

Watching staid scientists, engineers, and army personnel cheering and hugging each other like euphoric teenagers after the successful Trinity blast in Oppenheimer, I was reminded of dust-coated figures exuding an air of self-congratulation in the desert of Pokhran in 1974 and in 1998.

Filmgoers in India (the Nolan movie’s third-largest market, grossing Rs 73.20 crore in its opening week) might see Oppenheimer as an exotic film with foreign concerns. But there are insights here with relevance to our own nuclear history.

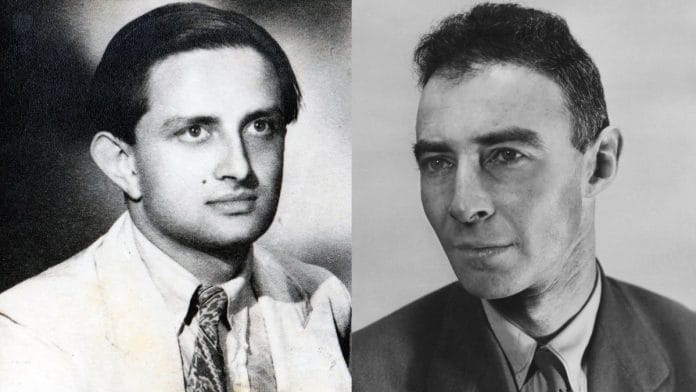

The obvious counterpart to Oppenheimer is the brilliant Homi Bhabha who set up the country’s atomic energy establishment and pushed for the bomb. But in my view, the person who better signifies the ethical concerns of the film is his successor, Vikram Sarabhai, who headed the Indian Atomic Energy Commission from 1966 to his untimely death in December 1971, two-and-a-half years before India staged its first nuclear test.

The most morally astute of India’s scientific pioneers, Sarabhai tried to bring a humanitarian perspective to the issue of nuclear weaponisation and to rescue it from a simplistic binary pitting inaction against bellicosity by expanding India’s range of options. He was overridden, however, by a powerful cabal of scientists, engineers, and bureaucrats and an insecure prime minister. There is a correspondence of sorts in Oppenheimer where the eponymous scientist, after serving the needs of the political and military establishment, is marginalised and victimised by the public official who hired him to build the bomb.

All this happened a long time ago. Nolan, who grew up “in the shadow of nuclear weapons in the early ’80s in the United Kingdom”, might have been exorcising a childhood ghost. But for today’s youth, as his teenage son told him, the nuclear threat is “just not something anybody worries about anymore”.

There are other forms of annihilation around the corner, however. And interestingly, it is Nolan — whose 2014 superhit Interstellar showed astronauts vaulting into space and time for solutions to Earth’s looming environmental catastrophe — who now feels compelled to evoke a Promethean figure as a cautionary hubristic narrative from the past.

Amrita Shah is the author of Vikram Sarabhai-A Life. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)