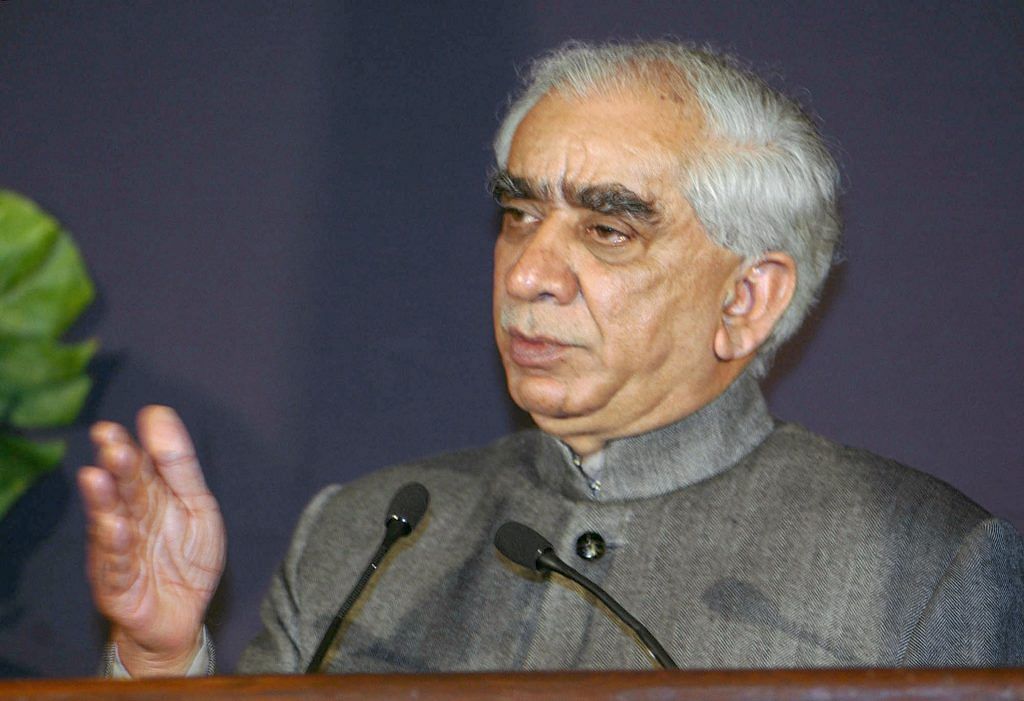

For the first time, son Manvendra Singh writes about Jaswant Singh on his 80th birthday in an exclusive to ThePrint.

My father, Jaswant Singh, doesn’t normally read sports news, especially if it doesn’t relate to his beloved dressage, show jumping, three-day eventing or other horse-related activities. So it took me by surprise when he asked me about my reaction to Michael Schumacher’s skiing accident at the fag end of 2013. We discussed it in considerable detail, and that conversation replays in my mind frequently now. Eight months later, he suffered a similar head injury, and has remained in the same condition as the celebrated motor racing champion.

I read every news story there was about Schumacher, but all were couched in immense privacy and secrecy that his family had cloaked around him. After more than three years of seeing my father in that state, the Schumacher family’s secrecy makes total sense to me. Only the near and dear ones can fully comprehend what that privacy means. Some of his closest friends ask, even visit, but don’t see him. The only friend who visits regularly and comes away teary-eyed every time is Advani.

The closest friend, of course, can’t see, visit, or talk to him because he too remains in the same condition—that is Atal Behari Vajpayee.

Atalji and my father maintained an extraordinary bond that defied all conventions of political friendships. In fact, the only thing common to both was the deep attachment to words—verse for one, and prose, the other. Their family backgrounds and upbringings couldn’t have been more different, and yet they bonded very deeply. It wasn’t for nothing that my father was labelled Atalji’s Hanuman, a sobriquet neither sought to deny. At the root of the closeness was transparency, indeed a rarity in public life.

He believed in being open and accountable to the public for his actions. Here is a little known episode that showed his commitment.

From after the midnight of 24 December 1999, every night, a lady would call my father on his home number. She would scream, cry, abuse, threaten suicide, and utter anything that came to her mouth. Despite being a cabinet minister, he picked up the phone call in his bedroom, and did not let it be attended by a staff member. The woman was the wife of a crew member on IC-814 that had been hijacked to Kandahar, and she would call to plead for help and intervention. The calls became a ritual. She kept saying, “You are not doing anything to save my husband.” My father would listen quietly.

Later when the matter was over, and the aircraft had come back on the 31st, she visited my father with her husband early on 1 January, 2000. She brought flowers, thanked him profusely and even apologised.

It was only much later that I mentioned these calls to a senior friend from the Indian Foreign Service, and an attendant was placed to answer calls through the night.

In fact, it was the same IFS official who later remarked that the diplomatic service, the world over, is a clique, an exclusive club, whose members work hard to ensure entry remains restricted. Limited membership is the hallmark of exclusivity, he said, “And your father is the only non-member who has been admitted by diplomats as one of their own for his intellect”. This is probably among the most admiring observations made about him during his career in office, and outside of it.

On dvitiya tithi, shukla paksh in the month of posh, an audio-visual video went viral in various Rajasthan social media groups. The music was one of the well-known folk songs, and the visuals were a walk down memory lane of my father’s career in politics. The date was his birthday according to the Indian calendar system, born as he was in Samvat, 1994. The video was crowd-sourced, and crowd-produced, and a most appropriate 80th birthday gift. By the Gregorian calendar he is 80 today, though native celebrations have already happened, audio-visually. Like the Indian birthday, this too will be marked in privacy at home.

His deep sense of privacy is what really made him an oddity in Indian politics, a system unused to a sense of space and private life. This desire to maintain privacy came up in a conversation soon after the Jinnah Karachi episode that caught L. K. Advani in a storm. Rumour had it that the party president-ship may well land on my father. An ideologically connected journalist said to me, “Hopefully your father won’t take it”. When I asked my father, he said the compromises with privacy would be more than what he could handle. So the matter ended there, but not the episodes with Jinnah.

At the end of January 2006, my father led 86 pilgrims to Hinglaj Mata in Las Bela district, Baluchistan. It hadn’t been done since 1947 and took him much effort to work through both Indian and Pakistani governments. Once the westernmost temple in ancient Hinduism, Hinglaj, has a special resonance in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Bengal. On the way back to Karachi from Hinglaj, Omkar Singh Lakhawat, then a Vasundhara Raje baiter and now a drum-beater, said to me, “I hope he isn’t going to Jinnah’s tomb, because the Hinglaj visit could make him a Hindu leader”. More than three years later, the reaction to the release of his book on Jinnah caused him deep anguish, and pain. Ironical, given that Jinnah’s grandson Nusli Wadia has an enduring, and endearing, friendship with him.

At the end of his political career he wanted to represent Barmer, and write a political biography on late C. Rajagopalchari, his ideological mentor, if there was one. Alas, that was not to be. He could not represent Barmer, which caused him much anguish. But there is no Sanjeevani to help him, since Atalji’s Hanuman can’t fly now.

Manvendra Singh is Jaswant Singh’s son and an MLA from Rajasthan.