The idea that all public initiatives to improve well-being are failing or dispensable is evidently wrong.

In recent years, a debate has raged in India on what is the level of poverty in the country and whether it has changed, either to reflect the arrival of a new India or the persistence of an old one. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government stopped producing official estimates of poverty when it abolished the storied 65-year-old Planning Commission.

This has, however, only cemented the impression that the debate on poverty estimates has become something of a free-for-all.

The official estimates on poverty, and most of the debate, both in recent years and much earlier, have focused on the total quantity of the goods, including food, clothing and other essentials of life, consumed by ordinary Indians. But it has long been understood that this is only a part of the picture of poverty in a country. The well-being of a person is shaped by multiple factors, including whether she is healthy, educated, has access to clean water and surroundings, and has social acceptance.

Also read: Extreme poverty in the world is declining, but not fast enough: World Bank

The current government, like previous ones, has recognised this through various initiatives (for example, through the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan or more recently, the Ayushman Bharat). These may be a case of well-packaged more than well-thought out, but they are at least nominally aimed to deliver social services and to improve the conditions of life. It is, therefore, of interest and importance to ask whether well-being in these various aspects has improved over substantial lengths of time, especially for the most deprived.

It is this issue that has been addressed by the newly released “multidimensional” poverty estimates for India by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Putting aside some quarrels with the methods used, the larger story that underlies the numbers is what is of public importance. Improving the methods, however warranted, seems unlikely to overturn the broad conclusions, including in particular at least three points.

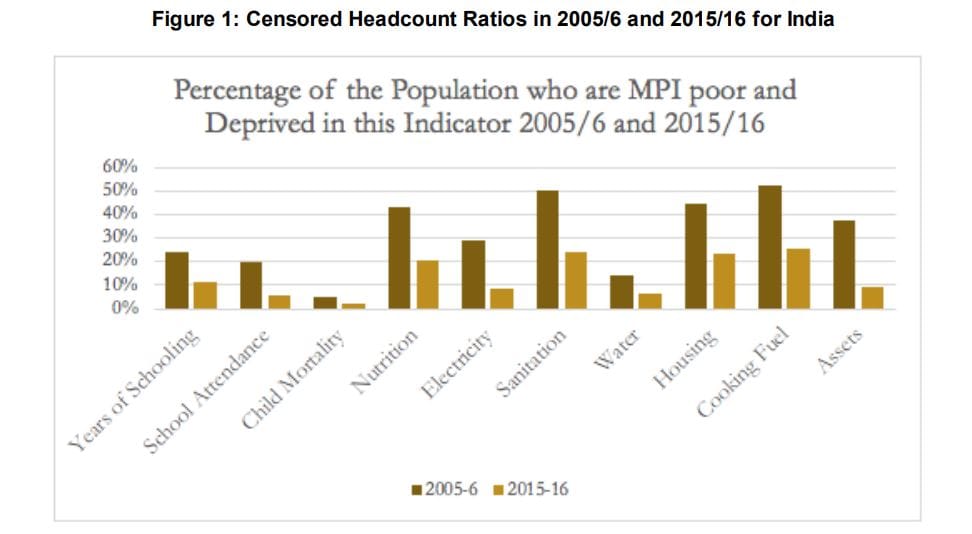

First, for the measures of deprivation considered by the authors, there has been an improvement across the board (See Figure 1 and Table 13 here).

In particular, there have been noteworthy gains in relation to a variety of areas, including sanitation, access to cooking fuel, housing, water, electricity.

But not all important aspects of well-being have been considered and the bar for non-deprivation has been set far too low in a number of cases.

There may also be underestimation of some deprivations because of the way the data has been generated and treated. Gains in certain areas, such as child mortality, have also been weak. Nevertheless, the picture that emerges, of improvements across the board, is noteworthy.

The measured improvements in multidimensional poverty are apparently not because of an unbalanced pattern of improvement only in specific areas (something that would otherwise be a distinct possibility due to the method used to calculate overall deprivation).

Also read: Poverty or inequality: What is more important for India and Indian economists

Second, there have apparently been improvements in all dimensions considered, and across regions and social groups, with the rate of improvement being in each case the greatest for the most deprived. But differences in the level of deprivations are still great, with marked gaps based on caste, religion and region. India is estimated still to be the single country with the largest number of “multidimensionally poor” in the world, 364 million (at least when using the methods of the report).

The level of deprivations in the worst-off districts in the country (such as Alirajpur in Madhya Pradesh) is comparable to that in the most deprived parts of the world (Sierra Leone in Sub-Saharan Africa). However, the level in the best-off districts (in Tamil Nadu and Kerala) is comparable to that in some of the less deprived, although still far from the least deprived, parts of the world (Eastern Europe and South America) [See p.27 here] . The considerable gap between north and south India (see Figure 7, p. 27) provides another dramatic illustration. It suggests the potential for growing economic and social tensions as a consequence. These have already begun to manifest as a result of the greater population growth in north India, which in turn has roots in social deprivations since better education and health lowers fertility rates. This may bring electoral consequences in future and has already led to a controversy over possible changes in the formula for distribution of fiscal resources to the states.

Third, the period covered by the survey, 2005-06 to 2015-16, was almost entirely under preceding governments (UPA I and II). The observed improvements cannot be attributed to the present government. It is more likely that economic growth in combination with government programmes in specific areas, established and administered in the preceding decades, made the difference.

From this standpoint, it is far from obvious why the UNDP country director chose to associate the improvements that have been registered with the Prime Minister’s formula of Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas. Although it is certainly true that the gains are “in line with” the slogan, they are not a product of it.

The conclusion to be drawn is a broad one. It is likely that the diminishment of some deprivations has resulted more from public interventions, and that the diminishment of others has resulted more from the growth of private incomes. They do not in themselves imply the superiority of a specific economy policy. The improvements suggest, instead, something less dramatic but more significant: the need for policies to be framed and executed that are based on commitment to the well-being of the people of India in the diverse aspects of their everyday life.

Also read: PM Modi is writing letters to 100 million families to educate them about Modicare

One-point public policy ideas presently in fashion, such as that of replacing a range of public actions to improve conditions of life with a single Aadhaar-linked cash transfer, pay insufficient attention to the range and depth of the initiatives required to bring about continued improvement in living conditions. The idea that all public initiatives to improve well-being are failing or dispensable is evidently wrong. It is also true that India’s state often performs poorly on the ground, and is sometimes even rapacious. It can benefit from comprehensive reform. The progress should have been faster still.

Growth in incomes is similarly not dispensable, even if it does not suffice to heal all ills. A sensible approach to promoting the public good must avoid such false oppositions, and their associated fads and fashions.

The author is an Economist at the New School for Social Research, New York.

The writer has absolutely no credibity what so ever. She Journalism is bias and all her stories based on lies and to benifit 1 Political party PMLN. This lady has a personal grudge with Imran Khan and all her stories and tweets confirms this. She is one of the Most corupt journalist of Pakustan. Giving this piece of crap article a place on ur website shows your level

I have been working in the field of nutrition in rural India for the last 25 years.It is my personal experience poverty and under nutrition among the children and pregnant and lactating mothers have not improved as it should be.ICDS is one very important platform to intervene in this aspect.But most unfortunately it is still under utilized.If more emphasis is given on ICDS…I am sure it has the enough potential to bring a radical change in the present grim scenario of under nutrition in India.